Junk Bonds Aren’t Going to Save You

Junk Bonds Aren’t Going to Save You

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In the midst of this month’s stock-market tumult, it might be tempting to look at total returns on U.S. high-yield debt and conclude that all is well in the bond market’s junkyard.

After all, speculative grade U.S. corporate bonds are practically the only segment of the global debt market that remain positive for the year, according to Bloomberg Barclays data. It’s been a rough October for high yield, to be sure, but its 1.21 percent decline as measured by Barclays pales in comparison to the 9.1 percent drop in the wide-ranging S&P 1500 Index, which combines the S&P 500, MidCap 400 and SmallCap 600 indexes. Even the riskiest credits of all, those rated CCC, have managed to hang in there — so much so that Bloomberg News recently concluded that junk credit investors are barely flinching at the violent swings in stocks.

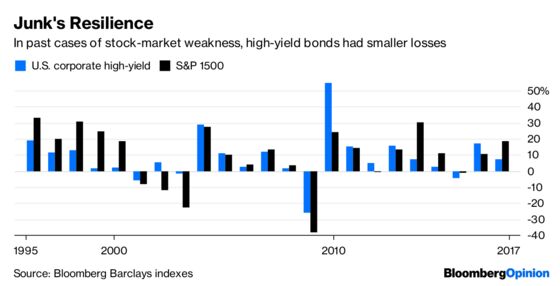

The thing is, it’s not all that unusual for high-yield bonds to hold up better amid bouts of market turmoil than their equity brethren. In fact, in data going back to 1995, each of the four times the S&P 1500 has fallen by more than 1 percent (in 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2008), junk bonds’ losses were smaller. In 2001, high-yield debt even rallied.

But if you focus instead on the most vulnerable industries within high-yield debt, you’ll find the very same laggards that have been dragging down the stock market: homebuilders and automakers. This shouldn’t come as a shock, considering both groups are sensitive to rising interest rates.

Shares of U.S. homebuilders and automakers have entered bear-market territory, with both down more than 30 percent in the months since the S&P 1500 reached an all-time high in January. By comparison, the Bloomberg Barclays high-yield home construction index has fallen more than 3 percent in 2018 and auto bonds have tumbled more than 6 percent. While the absolute numbers aren’t as striking in high yield, the magnitude by which the sectors are trailing the overall market is similar.

It’s probably still too soon to say if the market’s volatile October is the beginning of the end of the long bull market in stocks and other risky assets — though it’s sure getting ugly. But traders are running with the theory that mixed corporate earnings might be a sign that the profit peak has passed. On top of that, data released Wednesday showed U.S. purchases of new homes fell more than estimated in September to the weakest pace since December 2016. Higher mortgage rates may be curbing demand from would-be buyers.

It’s easy to see how this is weighing on a company like PulteGroup Inc. through its stock price, which fell to the lowest since January 2017 on Tuesday. But just as importantly, the yield on some of its senior unsecured bonds due in 2021 reached the highest since it was issued in early 2016. The yield differential, or spread, between the debt and benchmark Treasuries climbed above 1.5 percentage points to the widest since July 2. The spread on truck maker Navistar International Corp.’s bonds maturing in 2025 is at similarly lofty levels. Both are among the largest components of their respective Bloomberg Barclays sub-indexes.

Maybe it’s because junk bonds are so illiquid relative to public equities that investors have a hard time noticing that risks are starting to bubble up. Or maybe it’s because as the price of oil has declined, energy companies are avoiding the kind of wipe-out they had in 2015, when crude tumbled and the spillover to high-yield debt dragged down the entire market. The lack of new supply has also buoyed junk-rated securities throughout the year.

This complacency could also be because it’s easier to think of the market as a whole, rather than by sector — and, as I’ve written before, that’s just how some people appear to be trading, thanks to exchange-traded funds. That said, some investors in mutual funds are taking notice, with Lipper data estimating $2.1 billion of outflows from high-yield funds at Monday’s close, JPMorgan Chase & Co. analysts wrote. Not only that: investors are paying the most since 2016 to protect against defaults by high-yield borrowers, according to an index of credit derivatives.

A junk-bond implosion might not be imminent. But I wouldn’t exactly call them “a shelter in the global equity storm” either. If risk-off sentiment intensifies, the worst stocks and the worst bonds will be one and the same.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.