Fears Over U.S. Missile Shield in a Japan Suburb Hobble Abe’s Plan

Fears Over U.S. Missile Shield in a Japan Suburb Hobble Abe’s Plan

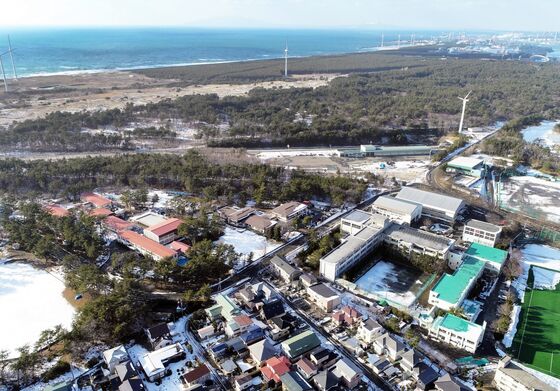

(Bloomberg) -- The sleepy northwestern Japanese suburb of Araya seemed like the perfect place for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to put a U.S. anti-missile system. The area had reliably backed the ruling party and had first-hand experience of a North Korean rocket flying overhead.

That is, until residents began to worry that Lockheed Martin Corp.’s Aegis Ashore system might make their pocket of homes nestled near rice fields and the sea a prime target for Pyongyang in any conflict. Opposition quickly rallied against the project, helping oust an upper house lawmaker from Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party in July and forcing the Defense Ministry to redo site surveys.

“I don’t think Aegis Ashore is needed, but at least I want them not to put it right next to this residential area,” said independent lawmaker Shizuka Terata, 44, who defeated the LDP incumbent in a district that had supported the party in 14 of the past 19 elections. “As the mother of a child, I hated the idea.”

The push back is the latest sign of the limits of Abe’s efforts to balance Japan’s deep-seated pacifism with renewed threats from North Korea and a demanding ally in U.S. President Donald Trump. The $5 billion anti-missile system faces a likely delay if not a bigger rethink: the Defense Ministry’s 2020 budget request includes money for purchasing the missile interceptors, but none for preparing the site.

Moving ahead with the plan would require Abe to either push past or win over local opposition, with 60% of Akita residents opposed to the deployment, according to a July poll by the local Sakigake Shinpo newspaper. Another alternative is to pick another site in northern Japan, at the risk of sparking a similar reaction.

Abe was counting on the Aegis Ashore system for tracking and intercepting missiles to meet two goals: protecting against North Korea and assuaging frustration over Japan’s lopsided relationship with its sole ally, the U.S. Since taking power in 2012, Abe has bolstered military spending each year and purchased American weapons systems such as the Aegis Ashore and F-35 stealth fighter jets, which are also made by Lockheed.

Japan is the largest foreign buyer of the plane considered the most expensive U.S. weapons system, which Tokyo likes to note when Trump gripes about bilateral trade deficits. Even so, Japan’s defense spending was at about 0.9% of gross domestic product, lower than the 3.2% in the U.S., World Bank data show.

The anti-missile system would help satisfy the U.S.’s long-standing demand for Japan to take a bigger security role, despite a promise to provide for its former foe’s defense. During a meeting of foreign and defense ministers from both countries in April, they reaffirmed their vow “to bolster capability and enhance their respective integrated defense for both air and missile threats, including through the timely and smooth deployment of Japan’s Aegis Ashore.”

Staying on the right side of the U.S. has grown more urgent under Trump. The U.S. president has mused to confidants about withdrawing from a six-decades defense treaty with Japan and complained in public about the pact because it doesn’t oblige Japan’s military to come to America’s defense.

“There’s never been a president who talked publicly about dismantling the U.S.-Japan alliance, so there’s been no debate about that,” said Yasuhiro Takeda, a professor at the National Defense Academy of Japan in Yokosuka, south of Tokyo.

But the Aegis Ashore situation underscores the challenge in meeting those demands. Besides budget pressures and personnel shortages stemming from Japan’s aging population, Abe also faces a deep-seated pacifism among a public wary of repeating the mistakes that led to World War II.

So, despite resentment over the presence of thousands of U.S. troops and a fear of being dragged into America’s conflicts, many also see efforts to build a more independent military as anathema. Abe has repeatedly put off plans for a relatively small revision to the U.S.-drafted pacifist constitution, which would make explicit the legality of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces.

Takeda, who wrote a book on the theoretical cost of defending Japan without the security treaty, concluded it was unrealistic at any price. Instead, the country should seek to ease the burden on the U.S. by bolstering its own capabilities in specific areas, including missile defense, Takeda said.

The reaction in Akita shows that course is fraught with difficulty. Akita has been on the front lines of North Korea’s missile threat since 1998, when the country’s rudimentary Taepodong rocket flew over the prefecture, raising alarm in Japan about its secretive neighbor’s arsenal.

North Korea launched two more missiles over Hokkaido to the north in 2017. The country considers Japan its mortal enemy and has hundreds of missiles that potentially can strike all parts of the country.

The Defense Ministry sought to persuade local people that the site in Akita and a second one at Hagi, in the southwestern prefecture of Yamaguchi, were the only feasible options for the batteries. Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya reiterated Friday that the two prefectures fulfilled the main criterion of providing maximum coverage.

Locals in Akita are concerned about the site’s proximity to schools as well as local government offices that would be in charge of coordinating a response to any emergency.

“I think people understand the need for it,” said former Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera. “It’s about where to put it. Of course there are a lot of people who would prefer not to have it near them,” he said in an interview.

Sleeping Official

Mistakes in the ministry’s paperwork and an official who dozed off at an explanatory session galvanized local opposition to the deployment. Some have also expressed doubts about the system’s effectiveness against a new generation of North Korean missiles that fly at a lower trajectory.

“Now there are low-flying cruise missiles and they may not be able to detect them,” said Masashi Sasaki, 69, a former railway employee who lives with four generations of his family on a street close to the proposed site in Akita and is campaigning against the deployment. Among his plans is a “human chain” demonstration to draw attention to the unsuitability of the site.

“We must never allow a war,” Sasaki said. “We mustn’t allow this place to become a trigger for war. So we can’t allow it to be located here. It’s our duty to refuse it decisively.

To contact the reporters on this story: Isabel Reynolds in Tokyo at ireynolds1@bloomberg.net;Emi Nobuhiro in Tokyo at enobuhiro@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, Jon Herskovitz

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.