Japan’s Long Deflation Battle Is Warning for Post-Virus World

Japan’s Long Deflation Battle Is Warning for Post-Virus World

(Bloomberg) -- The Covid-19 shock could spur an acceleration in global inflation driven by massive monetary and fiscal stimulus or a spell of deflation as demand craters. Japan’s experience suggests the latter is the bigger risk.

Years of anemic prices after the bursting of an asset bubble in Japan at the beginning of the 1990s prepared the ground for a deflationary tumble late in that decade. The bad news for Japan, and possibly the precedent for others, is that the world’s third-biggest economy is still struggling to get prices rising again.

“Until around 1997, the Japanese thought the nation could regain its economic mojo, but the financial crises and the tax hike shattered those hopes,” according to Takao Komine, former head of an economic research department at Japan’s economy ministry from that time. “This was the turning point for those expectations.”

The worry is that a similar pattern takes root across other developed economies after years of feeble price growth. Under that scenario, the coronavirus blow entrenches a deflationary mindset, where people hold off buying everything from household appliances to new homes because they think they’ll be cheaper in the future.

And as Japan’s experience shows, even decades of near zero interest rates and quantitative easing haven’t been enough to turn that mindset around.

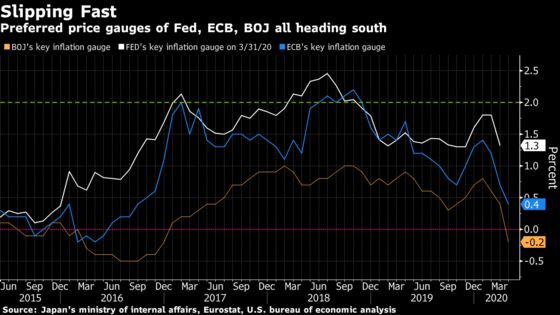

Plunging global demand, constrained activity and sharply lower oil prices could act as the triggers that send inflation negative across many economies after years of weak prices following the global financial crisis. Once that happens, the danger is prices keep falling.

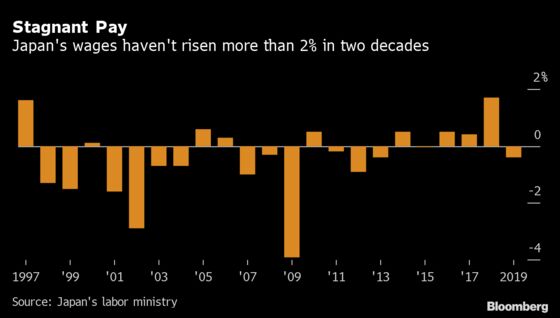

Wages offer another signal of deflationary danger. If falling prices give reason for consumers to delay expenditure and companies reason to postpone investment, lower wages can form a part of this negative cycle.

The six-month moving average for Japan’s monthly wage growth dipped below zero for the first time in mid-1998. The average didn’t turn positive again for nearly seven years after that.

The cost of services is another measure to watch, because while commodity price fluctuations can complicate the interpretation of price trends, service prices more closely reflect the fundamental state of incomes and demand in the economy. Steady gains in service prices indicate solid inflationary pressure and vice versa.

“The lack of movement in service prices is one of the key pieces of evidence showing a deflationary mindset,” said Kazuo Momma, former Bank of Japan chief economist. “After years of no inflation, Japanese people see prices as something that stay more or less the same. Once that viewpoint is ingrained, it’s almost impossible to change it.”

For around 15 years, Japan had little in the way of service sector inflation and it still doesn’t have much.

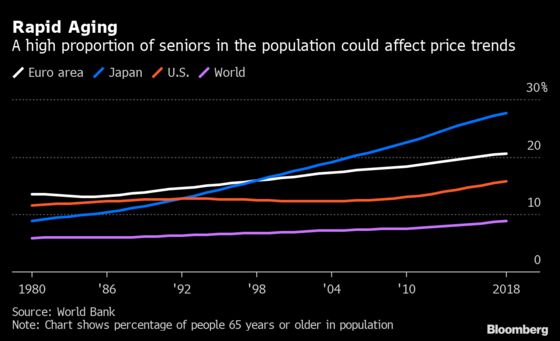

Japan’s shrinking and aging population is another factor highlighted by researchers and economists to explain its deflation battle. On the demographics front, Europe’s outlook doesn’t look great either.

“With working-age population growth projected to decline further by 2040, the negative demographic impact on the natural rate in Japan is likely to increase, which may further limit monetary policy’s role in reflating the economy,” IMF economists wrote in a report in March, referring to the rate of inflation that can achieve full employment.

If deflation takes hold, the government and central bank must work closely together and forcefully, according to Paul Sheard, a senior fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School, who has watched Japan as an economist for more than three decades.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s big mistake was to raise the sales tax twice when the BOJ was doing all it could to boost prices, he said. Until the pandemic struck, Japan’s budget balance had improved under Abe thanks to the tax increases and an economic expansion.

“The problem has not been what the BOJ has or has not done; it is the fact the aggressive monetary policy shift under Governor Kuroda all along was a kind of ‘Trojan Horse’ for pursuing fiscal consolidation,” Sheard said. “If the goal was to end deflation and secure low inflation, this was a wrong-headed approach.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.