J.C. Penney Couldn't Find a Way to Shake Off Its Identity Crisis

J.C. Penney Couldn't Find a Way to Shake Off Its Identity Crisis

(Bloomberg) -- For middle-class Americans in the 20th century, J.C. Penney was one of the first places to look when you needed work pants or underwear, toys or towels, chairs or china. Even if you didn’t live anywhere near one of its stores, the iconic mail-order catalog made its goods available to anyone. As Penney’s longtime slogan promised, “It’s All Inside.”

But as mall development spread in the 1970s, customers gained access to wider selections and new fashions. The internet would eventually offer even more. Like its “everything store” rival Sears, J.C. Penney couldn’t figure out how to stay relevant in this new era.

J.C. Penney filed for bankruptcy on Friday, citing debt of about $8 billion — a burden that finally became too much to bear.

The company’s bankruptcy filing in Corpus Christi, Texas, included $900 million of financing to fund the company through restructuring, including $450 million of fresh capital.

As the old saw goes, the end for the 118-year-old chain came gradually and then suddenly. A parade of chief executives tried different game plans in recent years, changing logos, pricing strategies, store layouts and the merchandise itself. Decisions were made and then undone. Nothing worked. In the end, the department store was finally done in by a force no retailer could have foreseen — a global pandemic that led to a near-total shutdown of the retail sector.

“The American retail industry has experienced a profoundly different new reality, requiring J.C. Penney to make difficult decisions in running our business,” Chief Executive Officer Jill Soltau said in a statement. “The closure of our stores due to the pandemic necessitated a more fulsome review to include the elimination of outstanding debt.”

Department stores face a collective crisis as an unprecedented economic shutdown due to the Covid-19 outbreak exacerbates many of the industry’s deep-rooted problems. In March, J.C. Penney temporarily shut down its 850 stores and put most of its 95,000 workers on furlough. The company soon began missing debt payments.

Some of America’s oldest retailers are in a similar position. Neiman Marcus Group, which also owns Bergdorf Goodman, and Stage Stores Inc. have filed for bankruptcy. Nordstrom Inc. is permanently closing more than 10% of its full-line stores. Macy’s Inc. has written down the value of its business and delayed its quarterly financial report for months.

Department stores shed $3 billion in sales in April from a year ago, according to Forrester Research. The situation will likely worsen, with more than half of mall-based department stores forecast to close by 2021, according to Green Street Advisors.

“The mall has lost its appeal,” said Morningstar Investment Service analyst David Swartz. Stores like J.C. Penney used to be the main attraction and “the problem is the big department stores aren't draws anymore.”

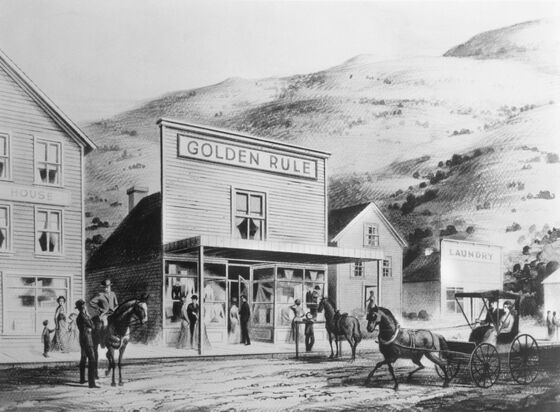

Golden Rule

The version of J.C. Penney that went bankrupt would be unrecognizable to the man who founded it.

James Cash Penney opened his first general store — then known as Golden Rule — in 1902 at the age of 26. He opted for the little mining town of Kemmerer, Wyoming, after rejecting Ogden, Utah, and its population of 16,000 as “too big.” His outpost sold dry goods, Levi’s overalls and women’s shoes, promising shoppers good customer service and fair prices. It was cash only; Penney didn’t accept credit and wouldn’t for another half-century.

He expanded throughout the West, renaming his shops after himself and shifting headquarters from Salt Lake City to New York City as he grew his store network across the continental U.S. To support this growth, Penney agreed to take his company public on Oct. 23, 1929, less than a week before a stock market crash ushered in the Great Depression.

Penney’s stores survived and became a staple of suburban shopping centers. The first job that Walmart Inc. founder Sam Walton held after college was at a J.C. Penney, where he learned the basics of retail. Over decades, J.C. Penney established itself as a mall anchor where families went to purchase back-to-school outfits and appliances for their homes.

The retailer’s ambitions grew beyond clothes and home goods. It would go on to acquire an Omaha supermarket, a Pittsburgh-based drug store chain and bank from Delaware. By the 1970s, J.C. Penney operated more than 2,000 stores across its brands. In 1971, the year James Cash Penney died, his company opened its biggest shop yet, a 300,000-square-foot behemoth in a suburban Chicago mall. In the ’80s and ’90s, it expanded its drugstore business, started a TV shopping network and bought a Brazilian department store. At its height, J.C. Penney had almost 300,000 employees.

By the turn of the century, amid the rise of online shopping, J.C. Penney’s biggest strengths had become incurable flaws. It was once the largest catalog retailer in the U.S., but mail orders were quickly becoming obsolete. The suburban malls that J.C. Penney called home began struggling to attract shoppers. The company needed a savior.

New Direction

Brick-and-mortar retail still had plenty of success stories at the time. Target Corp. had remade its image and boosted sales with modernized stores, catchy advertising and partnerships with respected designers. Apple Inc. had pioneered a sleek new store concept that many considered revolutionary.

So in 2011, it might have seemed natural for stodgy old J.C. Penney to turn to Ron Johnson, the man responsible for both of those prior retail makeovers.

In January 2012, Johnson, newly installed as CEO, took the stage alongside his handpicked executive team in New York City to tell investors, analysts and media that J.C. Penney would move in a new direction. The presentation even had Ellen DeGeneres provide a voice-over.

Among the changes, store layouts would be rearranged around a central “town square,” and mixed racks would be replaced by mini branded sections selling labels such as Liz Claiborne and Martha Stewart. The logo was redesigned. Most jarringly for J.C. Penney’s cost-conscious clientele: coupons were out, replaced by “fair and square” pricing.

What followed was one of the most dramatic collapses in retail history. Shoppers rejected management’s changes and fled in favor of J.C. Penney’s rivals. Johnson’s first full year saw $4.3 billion in annual sales evaporate as the company reported a near $1 billion loss. Executives fired 43,000 employees, more than one in four workers, in that time. Johnson was ousted after 17 months.

‘Self-Inflicted Wounds’

J.C. Penney has struggled to reclaim its identity ever since. Mike Ullman, Johnson’s predecessor, returned to help stabilize the company. He reverted most of Johnson’s changes in an effort to win back shoppers lost during that era, including bringing back coupons. “We are still trying to fully recover from the self-inflicted wounds of the previous strategy,” Ullman said on a conference call in 2015.

Marvin Ellison, a former Home Depot executive who helped turn that home-improvement company around, took the reins of J.C. Penney that year. During his three-year tenure, part of Ellison’s strategy focused on driving sales with big-ticket items. So the department-store chain started selling appliances again, which it had walked away from in the 1980s. It also tried selling more private brands and toys. He looked to revamp everything from the company’s in-store hair salons to supply chains.

Ellison even wanted the company to push more into hospitality by offering business-to-business services for the hotel and lodging industry as a way to gain market share. His plans didn’t come without pain: Hundreds more jobs cuts took place under his watch, a move that was meant to save as much as $25 million a year. He departed the company at the end of 2018.

Soltau, the retailer’s first female CEO, filled the top role later that year. J.C. Penney exited the major-appliance business — again — and she announced a number of store closures. To get in touch with its core customer once more, she spent the first few months of her tenure surveying customers on what they wanted Penney’s to be like.

“It hasn’t been a great shopping experience, I think largely because the company had lost its sight on doing what’s right for the customer,” Soltau said in an interview in September. The company has tried to do more right for its customers lately, including revamping dressing rooms, adding home-cooking and makeup-application classes, and decluttering its merchandise selection.

But as with earlier efforts, executives couldn’t counter the forces working against J.C. Penney, from the rise of e-commerce to changing consumer tastes to the decline of the American mall. When the coronavirus outbreak took a huge bite out of sales, it was too much to handle.

While the company said it plans to continue operating through the bankruptcy, it acknowledged that it will have to close a meaningful number of its roughly 850 stores, a phased process that will begin in the coming weeks.

“These old department stores were physical marketplaces and now the marketplace has moved online,” said Poonam Goyal, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “They have tried to evolve with exclusive merchandise, a focus on experiences, pop ups and convenience. And while all these are good efforts, they still aren’t enough.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.