Brazil’s Coronavirus Splurge Is Sparking a Rebellion in Markets

Investors Rebel Against Brazil’s Rich-Nation Approach to Crisis

(Bloomberg) -- President Jair Bolsonaro’s stimulus spending spree won praise far and wide for saving Brazilians from the worst of the pandemic’s economic pain.

But now, as the worst of the health crisis eases, anxiety is mounting in financial circles about how he’s going to pay for it. Investors have been unloading the currency and stocks, sparking routs that are almost unparalleled in the world this year, and they’re increasingly refusing to buy anything but the shortest of short-term government bonds.

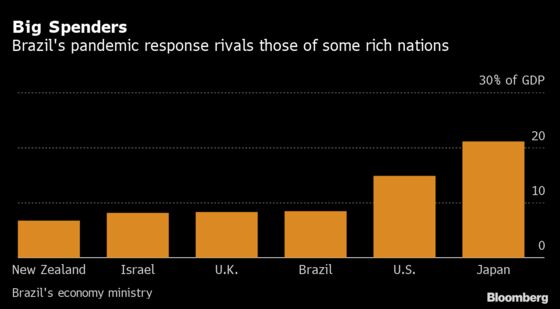

At $107 billion, Bolsonaro’s relief program looks more like the massive stimulus packages engineered by the world’s wealthiest nations than those cobbled together by Brazil’s junk-rated peers in emerging markets. Equal to 8.4% of the country’s annual economic output, it’s even proportionally bigger than the plans enacted by the U.K. and New Zealand.

All of which turns Brazil into something of a Covid-19 economic case study: Can a mid-tier developing nation emulate the fiscal and monetary response of the world’s most credit-worthy countries and get away with it? Or will it sink into financial crisis?

Arminio Fraga, perhaps Brazil’s most respected former central banker, says a full-blown disaster is a very real possibility now. “I can see mature economies doing all kinds of acrobatic moves with their central banks. That’s fine, they can,” says Fraga, who helped stave off a debt default back in 1999 and today runs a hedge fund, Gavea Investimentos, in Rio de Janeiro. “Here in Brazil, it’s different. We have a lot of debt.”

Of course, most rich countries have lots of debt too. The International Monetary Fund predicts that the U.S. and Canada will end this year with debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratios above 100% and says Japan’s will soar to 266%, all well above the 95% ratio that the Bolsonaro administration forecasts for year-end. But Brazil, with its long history of defaults and runaway inflation, doesn’t have the hard-earned credibility in markets that those countries have. Moreover, the pace at which the debt ratio is climbing -- it’s up 30 percentage points in the past five years alone -- alarms investors.

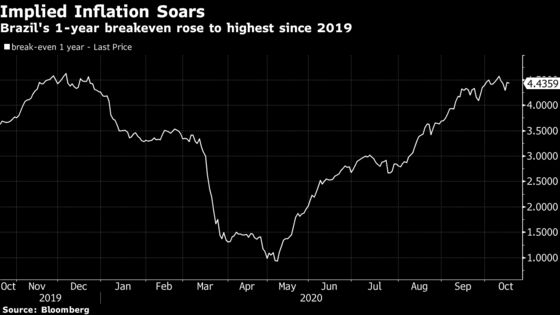

Expectations for inflation in Brazil, while nothing even vaguely resembling the hyper-inflationary years of the mid-1990s, are climbing quickly amid concern that the government lacks the political will to rein in spending.

Amid the pandemic, other developing countries, like Peru and Chile, actually produced more stimulus relative to the sizes of their economies, but they enjoy investment-grade credit ratings and started off with much smaller debtloads.

Corona Vouchers

In Brazil, the lion’s share of the stimulus -- some $57 billion -- was dedicated to monthly stipends for the poorest, who stayed fed and kept spending as the economy was shrinking. The cash transfers, which came to be known as corona vouchers, ultimately drove down poverty and sent Bolsonaro’s popularity soaring. The IMF applauded the response for averting a deeper economic downturn and stabilizing financial markets.

What has economists wringing their hands is how the president, a self-styled budget hawk, reconciles a record primary deficit with a sudden desire to make part of the aid permanent after the stimulus expires on Dec. 31. The IMF officials, in the same report praising the initial aid, cautioned that growing levels of public debt represented a risk to Brazil.

A primary budget gap estimated at 12.1% of GDP and growing doubts about Bolsonaro’s ability to find a way to pay for more social spending have roiled markets.

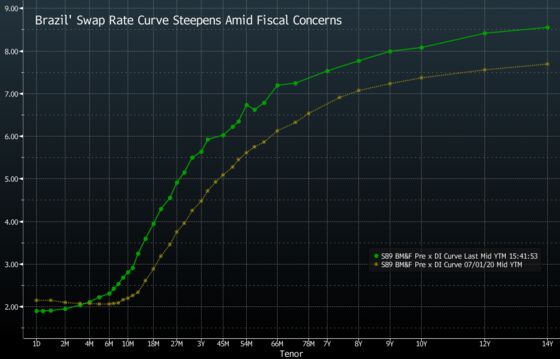

The premium traders demand to hold longer-dated debt has soared amid the increased risk, with swap rates expiring in about five years at 6.82%, up from 5.39% in July. Brazil’s real has tumbled almost 30% this year, dragging down dollar-based returns for stocks. The currency, already under pressure as record low rates eroded its carry trade appeal, has seen volatility soar as traders react to headlines about government spending.

Breakeven Rates

Inflation expectations have also shot up, with investors now pricing in annual price increases of 4.4% over the next decade, up from 3.8% just 12 months earlier.

Perhaps the most ominous sign is the difficulty selling longer-term debt, even as nations such as the U.S. flirt with the idea of offering securities with maturities of 50 to 100 years. In Brazil, the average maturity of local government bonds sold at auction was 2.36 years in August, down from 4.95 years a year earlier. Since then, the move toward shorter-term notes has only grown.

In bond auctions so far this month, for example, six-month notes -- the shortest term available with a fixed rate -- accounted for 44% of the fixed-rate debt sold, compared with just 11% during October 2019.

“Without reforms, it’s possible that the country faces another serious macroeconomic crisis,” said Alberto Ramos, an economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in New York. “High government spending has been a problem for Brazil for decades. Fiscal deterioration brought high inflation, low growth and the need from IMF help in the past. Today, the situation is not better.”

Budget Deficit

The shift to selling shorter-term bonds in recent months stemmed from investor concerns about the amount of public spending, Jose Franco de Morais, the Treasury Department’s public debt subsecretary, acknowledged in an interview. He expects things to normalize in coming months as investors gain confidence that outlays will be reeled in.

But the problem investors have with Brazil is its track record of excessive spending and allowing consumer-price increases to inflate away its debt. Brazil has defaulted on its external debt nine times since 1800, according to the book “This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly.” That’s tied for third-most globally during that span.

The country defaulted in 1987 and wasn’t able to resume payments until 1994, a year when inflation peaked at 4,923%. During the 2008 financial crisis, Brazil pumped money into public banks and reduced taxes to help dig its way out of recession. But temporary relief turned permanent, leading to budget deficits and eventual downgrades of its debt, which ultimately cost the government billions in higher borrowing costs.

“Our own internal dynamics are unsustainable,” Fraga said in an interview. “The response has to be broad and deep and it has to cover fiscal matters, which is difficult.”

Almost a decade after the 2008 crisis, Bolsonaro’s predecessor instated constitutionally mandated spending ceiling to help regain investor confidence. But Congress gave Bolsonaro a one-time pass to blow past it this year, and investors are anxiously watching for signals he’ll set the country back on the road to fiscal stability.

Future Generations

“The spending cap is a symbol, a flag that some of us in the trenches use to defend future generations,” Economy Minister Paulo Guedes said at an event this month. “We can’t go on with snowballing debt, high interest rates and high taxes.”

But so far it’s hard to tell what Bolsonaro is planning. His last pitch to pay post-pandemic aid whipsawed markets last month, leaving his own economic team to run damage control on growing concerns that the commitment to spending limits isn’t serious.

He since shelved future discussions until after next month’s municipal elections, leaving him with just a short window to hammer out a deal between when the polls close and the new year begins.

Morais said the fiscal rule will be respected and the next stimulus program will be smaller than some investors had feared. He added that there’s plenty of liquidity in the local bond market.

“Time will be working against the government,” said Roberto Secemski, an economist focused on Brazil at Barclays Plc. Investors ultimately want a plan “that tells us public indebtedness will stabilize.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.