In Global War for Talent, Language Becomes a Hurdle for Quebec

In Global War for Talent, Language Becomes a Hurdle for Quebec

(Bloomberg) -- Elham Kheradmand has the kind of qualifications that most tech-savvy economies would love to attract.

A PhD candidate in applied mathematics at Polytechnique Montreal, the 35-year-old has stellar grades and five years experience developing banking software in her native Iran. Yet in the Canadian province of Quebec, where labor shortages are rampant, her many interviews have failed to turn up a job offer. She has an inkling why.

“For us who come from other cultures, the language is a barrier, even though we have a high education,” said Kheradmand, who says she has learned to speak French, but lost some opportunities for not mastering it.

The French-speaking province is starting to pay more attention to students like Kheradmand as baby boomers retire and the strongest growth in years leave many jobs unfilled. Vacancies climbed 39 percent in the quarter through June, driving Canada’s 19 percent increase and worsening a labor shortage.

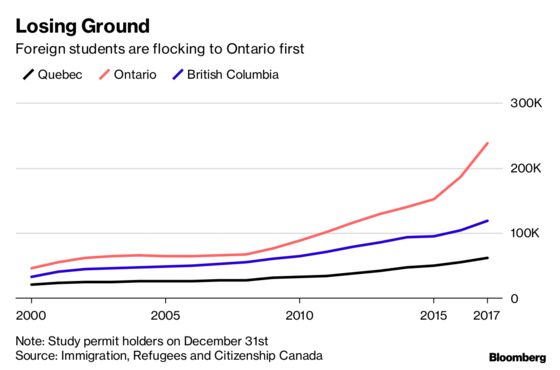

While Quebec has benefited from Canada’s growing popularity as a study destination in recent years, the country’s second-most populous province trails Ontario and British Columbia in its share of foreign students, which declined to 12 percent in 2017 from 17 percent in 2000. Over that period, the number of study-permit holders climbed 195 percent in Quebec, compared with 422 percent in Ontario, according to immigration data.

Part of it has to do with the language, as more than half of students are taught in French. The lack of government-led promotional efforts also held the province back in the past, according to a 2017 report by Institut du Quebec, an economic think tank. Debates over religious signs and isolated incidents against Muslims could have hurt at the margin too, casting the province in a less liberal light than the rest of the country.

Bad Signal

Now, the newly elected Quebec government of Premier Francois Legault has announced plans to cut the number of legal immigrants this year by 20 percent to about 40,000 to better integrate them into the workforce and society, he says. While it’s unclear how skilled workers will be affected and how long the new cap will last, the policy may send a bad signal as students compare universities’ offers.

Such uncertainties should be cleared quickly so as to not affect students’ decisions, said Mia Homsy, the Institut du Quebec’s director. As automation makes talent ever more crucial, “it’s very important for us to not only attract them, but also retain them,” she said.

Job Fairs

Data give a mixed picture of Quebec’s ability to retain graduates. In 2017, the number of foreigners who transitioned directly from a student permit to Canadian residency dropped 1.5 percent, compared with a 46 percent jump in Ontario, according to statistics from the immigration ministry. More encouragingly, the number of work permits granted to graduates, often a first step to applying for residency, rose 20 percent, against Ontario’s 6.8 percent increase.

In 2016, Quebec asked Montreal International, an agency that seeks to attract foreign investment to the city, to help raise the share of graduates who obtain a Quebec selection certificate -- the first immigration step in the province -- from an estimated 25 percent. In 2018, it added the goal of increasing the number of international students by 25 percent over three years, raising awareness with employers through such events as job fairs.

Great Potential

Beelogix, a consulting firm specializing in SAP SE’s supply-chain software, attended one of the fairs in November. The company of about 50 people, which was created in 2014, has been on a hiring spree, including of foreign graduates, according to business development director Annie Dubreuil. Not speaking French isn’t a deal breaker.

“It won’t stop us from hiring them if they have great potential,” she said. “We offer English classes, we could well offer French classes.”

That kind of flexibility is likely to become more widespread. Companies can’t afford to be as picky as they used to be given current labor market dynamics, according to Institut du Quebec’s Homsy.

It may also determine whether a student like software engineering major Qiushuo Li ends up working in Montreal when he graduates from McGill in 2021. The university recorded a 41 percent bump in foreign students in the past five years.

One of two people from his class in Chengdu, China, who chose Canada over the U.S., Li is now looking for an internship. So far, just one of the companies he contacted explicitly made command of French a requirement. While Li is learning the language, he’s not sure what he will do long term.

“If I feel like China has a more valuable opportunity for me I will go back,” he said. “If I find Montreal would accept me, value me for my skills, I will stay.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Sandrine Rastello in Montreal at srastello@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Scanlan at dscanlan@bloomberg.net, Jacqueline Thorpe, Steven Frank

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.