Brazil’s Biggest Employer of Trans People Flies Its Pride Flag

Brazil’s Biggest Employer of Trans People Flies Its Pride Flag

(Bloomberg) -- By 7:30 a.m. on a recent Tuesday, the line outside the Guararapes factory stretched to 80 people. Everyone hoped for a job—sewing clothes, mopping floors, serving food in the company cafeteria, and so on. The line forms again around noon under the hot, lunchtime sun, and the next day and the next.

With some 11,000 workers, the Guararapes Confeccoes SA is the biggest employer in Rio Grande do Norte state on Brazil’s northeast coast. In a typical month, the company hires around 100 people; during the busy holiday season, it might add eight times as many. For many residents of the capital city of Natal, it’s also their best bet: Unemployment is close to 14%.

Bya Ferreira worked in the factory gatehouse for 16 months, doing triage for the human resources department. Extroverted by nature, she started basically as a volunteer, sneaking away from her official job as an apprentice in the library. Eventually, she was officially transferred to the division.

“When I was giving orientation speeches, I could hear people discussing whether I was a man or a woman,” Ferreira said. “I was so proud to be the face of the company. HR is the company’s brain—it made me feel embraced.”

Ferreira is one of about 500 transgender workers at Guararapes, a quorum that, the company says, makes it the country’s biggest employer of trans people. It’s an unusual reputation for a company anywhere, let alone in a country that recently voted by a solid margin to elect President Jair Bolsonaro, who once publicly said he’d rather have a dead son than a gay one. The company’s chairman, Flavio Rocha, identifies himself as a creationist, opposes gay marriage and, after his own presidential bid failed, threw his support to Bolsonaro.

A live-and-let-live tolerance for all types of sex and sexuality is part of Brazil’s global reputation. Carnival incorporates a long cultural history of gender-bending and drag. Gay marriage is legal. The gay pride parade in Sao Paulo is one of the biggest in the world, with an estimated 3 million participants. In the past two years, the Supreme Court has made it easier for trans people to legally change their names and has defined homophobia as a crime on par with racism.

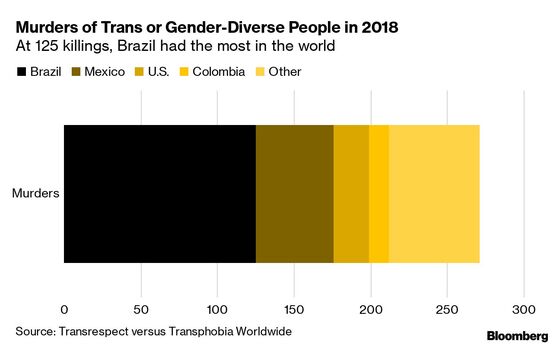

At the same time, Brazil is still deeply Catholic, and evangelism is on the rise. Bolsonaro’s Minister of Human Rights, Women and Family has outlined a strict “boys wear blue, girls wear pink” approach to gender identity. Brazil has long been the most dangerous place in the world for trans people, and it isn’t getting better. More than 150 LGBT people have already died by murder or suicide this year, on pace with 2018, according to Salvador nonprofit Grupo Gay da Bahia.

Anti-trans prejudice runs deep, said Fabio Mariano Borges, a sociology professor at ESPM-Sao Paulo. In the 1980s, a late-night TV Show called Gala Gay Ballroom featured trans women who worked in marginal employment as prostitutes or, at best, hair dressers or makeup artists. “Trans people in Brazil have always been in what sociology calls ‘a place of shame,’” he said.

That cuts against a lot of international corporate rhetoric, with its embrace of “diversity” and “inclusion.” Many of Brazil’s biggest companies, including Carrefour SA and Itau Unibanco Holding SA have declared their solidarity with LGBT people, including their employees and customers. Seventy companies belong to the Forum of LGBTI+ Companies and Commitments, a six-year-old group that pledges to implement 10 measures of LGBT protection and inclusion. This month, Guararapes joined them.

Founded in 1956 by Nevaldo Rocha and his brother Newton, Guararapes has grown into a $2 billion giant of fast-fashion, with 40,000 employees working in two factories, three distribution centers, 312 Riachuelo stores and other operations. The company manufactures more than 80% of the garments it sells and imports the rest, including a line of the popular U.S. kids brand Carter’s. It also makes licensed products with Disney characters and has developed collections with icons such as Karl Lagerfeld and Donatella Versace.

The Rocha family is now worth an estimated $1.7 billion. Nevaldo, who will turn 91 in July, still visits the Natal factory every day. “What I like most about this company is, it creates jobs,” he said. Many of the available roles don’t require much formal education—only about half of Brazilians have a high-school diploma—and wages are in-line with the national minimum of about $260 a month.

Myrella da Silva joined the employment line at the Natal plant in early 2018. Just 21, she had a mottled resume. She had sold perfume for three years until her street stand burned down; she thinks the fire was set by a customer who’d said trans people didn’t deserve to exist. She also made a living as a sex worker for a couple of years. At Guararapes, she was hired as a sewer, earning the minimum wage.

“A friend told me that here, they give opportunities for people like me and don’t discriminate,’’ said Silva, now 22. Her $280 monthly salary helps support her mother and two siblings, who all live with her. After 11 years of estrangement, Silva’s father has reached out. “He asked for forgiveness and said through all these years, he’d been praying for me,” she said. “I forgave him, but it’s still hard for me to call him ‘Dad.’”

With a population of 870,000, Natal is big and cosmopolitan enough to have an active LGBT community, and Guararapes became known for its sensitivity and flexibility. One day, Bya Ferreira’s supervisor asked her why she was turning her employee ID back-to-front. Ferreira explained she didn’t like to show the legal, male name printed there. A few days later, Ferreira received a new badge with her adopted name, she said. Shortly afterward, the company changed its policy.

Word of a trans-friendly employer traveled quickly. As more trans workers joined the workforce, the workplace continued to adapt. Last year, amid an international furor over who would get to use which bathrooms, the company affirmed that employees are welcome to use the facility aligned with their gender identity. Silva said it came as a relief, both emotional and practical. Prior to the policy change, she would sometimes spend her entire shift consciously not using the bathroom.

Not all the employees have been supportive. The workforce has a large evangelical contingent—one employee passed out a pamphlet titled “Jesus Christ is the Bread of Life” to coworkers and visitors last week. When the bathroom policy changed, one sewer quit in protest. Others grumbled.

Last year, Flavio Rocha resigned as the company’s chief executive officer to launch a presidential campaign, making opposition to gay marriage part of his platform. The position was based in his religious beliefs, not prejudice, he said, and he counts gay people among his good friends. A few months later, he decided not to run. He supported Bolsonaro instead and returned to Guararapes as chairman. He declined to comment for this story.

LGBT advocates were enraged by Rocha’s comments during his campaign, and they called for a boycott of Guararapes’s Riachuelo stores. The words still sting. “Riachuelo’s stance is a façade,” said Weber Fonseca, an activist and author of the 2015 book lgbtfobia. “All of their transgender employees are blue-collar workers—they’re not in the leadership.”

Rocha’s brief flirtation with the presidency was “a personal project,” said Marcella Kanner, the company’s marketing manager and Nevaldo’s granddaughter. “Riachuelo has no political ties.” Her focus now includes improving racial diversity at the highest levels, which are still mostly white while 65% of the workforce is black. Gender balance is better, she says, with 68% of leadership positions occupied by women, roughly mirroring the split in the workforce.

Flavio Rocha comes to the Natal factory from time to time. On the sewing floor, employees choose the music that blasts from the speakers overhead. Sometimes it’s “forro,” a rhythm popular in the region; sometimes it’s evangelical pop. Every two hours a horn blasts, reminding workers to get up to stretch.

“I’m not sure what to make of the comments he made during the presidential process,” Ferreira said. “Maybe they were for political purposes?” She met Rocha during one of his visits to the factory. He was nice, she said. He hugged her, and they posed for a photo.

— With Devon Pendleton

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Janet Paskin at jpaskin@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.