Soy Farmers Bet Against Peso Just as Argentina Needs Cash

In Argentina, They Are Betting the Farm on a Weaker Currency

(Bloomberg) -- Decades of political and financial turmoil have turned Argentine soybean growers into shrewd currency traders. Right now, they’re betting the farm on a weaker peso.

Farmers’ sales of soy have slowed to a crawl because they see the currency as overvalued. Growing stockpiles are unnerving buyers such as Glencore Plc and Bunge Ltd. that crush the beans and ship out meal and oil for livestock feed and cooking. Hoarding also deprives the government of exports just as it battles to reach a $65 billion debt-restructuring deal.

This isn’t the first time. Nearly every season, farmers on the vast Pampas crop belt hold on to soy for as long as possible, betting -- with great success -- against the peso, which has been falling for years. The longer they wait, the more pesos they receive for their harvests priced in U.S. dollars.

Hoarding takes two forms: physically, in sausage-shaped silo bags and grain elevators; or virtually, by handing them over to exporters under contracts that allow farmers to fix prices later.

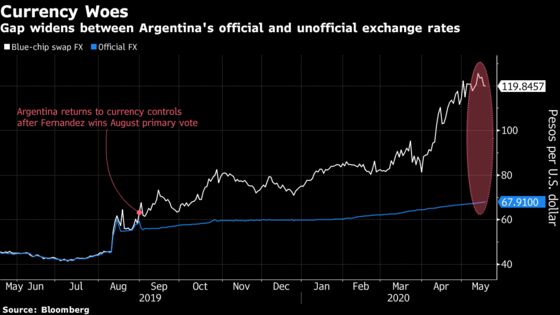

This year, the dynamic is becoming extreme. That’s because if growers sell beans now, they’d only receive about 45 pesos a dollar (the official, controlled exchange rate minus 33% of export taxes). Meanwhile there’s a free-floating exchange rate, accessed through a popular bond operation, trading closer to 120 pesos a dollar.

So farmers are waiting for the gap to narrow, especially with the central bank’s crawling peg steadily depreciating the official rate.

“With this gap in the foreign exchange rates, farmers won’t sell even a kilo of soy,” Pablo Adreani, an agribusiness consultant in Buenos Aires, wrote in a May 1 tweet.

The latest government data through May 13, with most soy harvested, shows farmers have sold and priced 12.7 million metric tons of beans, or 25% of the crop. That’s actually six percentage points more than at the same stage last year.

Worst Time

But the data hides the trend of recent weeks, with hoarding taking a grip at the worst possible time for the government. If talks with creditors for $65 billion in debt don’t succeed in the next couple of days, Argentina will default and risk a painful court battle if bondholders decide there’s little chance of an agreement.

Whatever happens, the nation desperately needs soy export revenues -- worth $17.9 billion last season -- to protect dollar reserves, fund Covid-19 stimulus spending and pay back loans.

This season, farmers traded a lot of soybeans early on, during planting, because they were sure Alberto Fernandez -- who emerged as Argentina’s likely next leader and went on to become president-elect -- would hike export taxes.

Between August, when Fernandez trounced incumbent Mauricio Macri in a primary vote, and mid-December, when he took office and first increased levies, farmers sold and priced 6.9 million tons. Since then, only 4.4 million tons have been handed over.

“Anticipated selling is the driver” behind the slowness now, said Agustin Tejeda, chief economist at the Buenos Aires Grain Exchange.

Whether sales are poor because of the early-season rush or currency speculation, the world’s largest agricultural trading firms are taking notice. All of them except Archer-Daniels Midland Co. process beans in Argentina.

Argentine farmers “have really stopped selling,” Greg Heckman, chief executive officer of Bunge, said on a May 6 earnings call. “And that -- just the overall difficulties there -- we don’t see that changing.”

The government seems to share Heckman’s view. In a controversial measure last week designed to secure soybean dollar revenues, the central bank said farmers who hold on to more than 5% of their crop can’t access soft loans. Since soy harvests in Argentina have become, in essence, dollar savings accounts, in return the bank is offering the next best thing: peso term deposits tied to bean prices.

That’s probably not enough for farmers like Francisco Perkins, who planted 3,100 hectares (7,700 acres) of soy this season on prime Pampas fields in Buenos Aires province.

Perkins took coverage on about 60% of his estimated harvest before Fernandez hiked taxes. Most of the other 40% is now getting bagged on his farms. He’s waiting for a better selling opportunity after global crop prices dropped this year, with soybeans for July delivery trading on Wednesday at $8.46 a bushel in Chicago. The yawning exchange-rate gap is also a big concern.

“I pay the next round of planting with this harvest, and the price of inputs will go hand in hand with the exchange rate,” Perkins said. “So keeping bags of soy is the only way to guarantee affording those inputs.”

Unique Challenges

Argentina’s soybean crushers want farmers to trade as much as possible because they lose money when idle capacity rises. Because they’re already facing a unique set of challenges this season, they’ve pushed for some sort of regulation to encourage selling.

First, Covid-19 brought unprecedented logistics problems. Then the soy harvest was hit by a drought, tightening supplies. Dryness is now costing crushers hundreds of millions of dollars in extra shipping fees because the Parana River has sunk to its lowest in decades.

Farmers aren’t happy with the latest round of intervention from the central bank, especially after a lawmaker in the ruling Peronist party drafted a bill in March to nationalize crop trading.

Growers are fed up with the annual calls to sell their soy as soon as it’s collected in the second quarter. Those calls were even heard when Macri’s agriculture-friendly coalition was in power.

“They question us for not selling it all in one go,” Perkins said. “But no business works that way.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.