Brains Behind Ultra-Dovish Policy Quits Hungary Central Bank

Brains Behind Ultra-Dovish Policy Quits Hungary Central Bank

(Bloomberg) -- Marton Nagy, the architect of Hungary’s ultra-loose unconventional monetary policy, unexpectedly resigned from his position as deputy governor of the central bank.

Nagy had held the broadest portfolio at the regulator, including monetary policy, financial stability and programs to boost credit in the economy. He resigned to take on “another important leadership assignment,” the central bank said in a statement on Thursday. Nagy, in a text message, declined to comment.

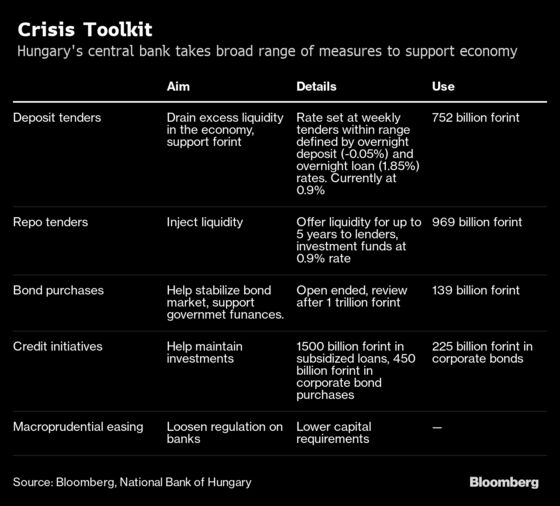

The announcement is a shock for investors for whom Nagy was the key contact to help decipher an increasingly complex web of monetary policy. Most recently, it involved the unusual combination of launching a quantitative-easing program to reduce borrowing costs on longer maturities while tightening short-term policy to arrest a currency slide during the pandemic.

“Marton Nagy’s comments, speeches, and public appearances always attracted vast crowds of market participants, as he was seen as the most influential Monetary Council member and trend-setter,” said Marek Drimal, a strategist at Societe Generale SA in London.

Nagy years ago had a falling out with Governor Gyorgy Matolcsy, a close ally of Prime Minister Viktor Orban, but the two had managed to repair relations to steer the central bank’s policy together. Matolcsy is known to have more of an interest in ideology and theory, while Nagy was seen as the person who made the governor’s vision a reality.

The forint reversed gains against the euro after the announcement. Barnabas Virag, a central bank executive director, will take over Nagy’s position temporarily.

Singular Voice

The 44-year-old Nagy became the almost singular face and voice of Hungary’s rate-setting Monetary Council, in contrast with emerging-market central banks in eastern Europe, including in Poland and the Czech Republic, which are known for boisterous debates and a cacophony of voices about monetary policy.

Nagy’s colleagues in the central bank often eschewed interviews and let the man who spent the past 18 years climbing the ranks at the institution speak for them. Even Matolcsy rarely made headlines about monetary policy, whereas Nagy’s comments regularly indicated policy shifts and resulted in moves in the forint’s exchange rate.

“Nagy was rightly viewed as the key professional” at the central bank, “providing a vital link between the bank and international financial circles,” said Mujtaba Rahman, managing director of the risk consultancy Eurasia Group. “He was also viewed as something of a check on governor Matolcsy’s fascination with low interest rates as the essential basis for economic growth.”

The currency weakened 0.3% to 349.95 per euro after the announcement on Thursday, compared with a 0.5% gain for the Czech koruna.

The one-man, one-voice setup, with rarely a vote of dissent at rate decisions, was appreciated by some investors for giving unified guidance on policy, though it also now raises the stakes for Nagy’s replacement.

‘Key Call’

“Nagy was always the key call or meeting for investors, whereas in Poland it’s always trying to determine who on the MPC is part of the dominant majority group,’ said Tim Ash, an emerging-market strategist at Bluebay Asset Management. “It will be interesting to see who replaces Nagy and how communication changes going forward.”

Nagy may go on to take a position as deputy chief executive of a planned banking group resulting from the merger of three Hungarian lenders, 24.hu reported, citing several unidentified sources. The new group, Magyar Bankholding Zrt., would become the second-largest lender in Hungary after OTP Bank Nyrt.

The abruptness of Nagy’s departure -- many of his colleagues at the central bank had no knowledge of his resignation until after it was announced -- suggested the move may have been a result of renewed conflict with Matolcsy, according to Eurasia’s Rahman.

For all his monetary-policy savvy, Nagy had his share of detractors. He often came across as overbearing, sometimes dressing down investors and economists at public events for failing to understand quickly enough a newly introduced policy framework or even for failing to make the sort of investment choices he deemed logical.

Sometimes it was also about the substance. In October, Nagy declared inflation effectively dead and said the era of robust price growth would never return. By February, he found himself battling the European Union’s fastest inflation with one of the loosest policies in the world just as the pandemic engulfed Hungary.

Still, Nagy usually found a way out. The central bank’s virus response had achieved a dual goal of raising short-term interest rates to stabilize the forint, while reducing longer rates to spur lending and help government borrowing. The monetary sweet spot may be the best opportunity for the central bank to find a replacement, according to Bluebay’s Ash.

“Hungarian markets have stabilized to an extent there is a window where the market will be relatively sanguine about the move,” Ash said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.