How Latin America’s Oasis Was Felled by a Stunning Market Rout

How Latin America’s Oasis Was Felled by a Stunning Market Rout

(Bloomberg) -- It was the best house on a bad block, the saying in financial circles went, an oasis in a region deemed too tumultuous for most investors. Now the house is on fire, the neighborhood is going downhill and those investors are struggling to comprehend what an unparalleled wave of violence and protest mean for Chile’s economic and financial future.

It’s barely been a month since the government set off the chaos with a move to raise subway fares by four cents. That little tweak ended up triggering a social explosion that sent the currency careening to a record low, hammered stocks and cost Chile its title as Latin America’s safest borrower, as measured by the cost to insure against a default.

Protesters are now calling for bigger pensions, better health care, less economic inequality and a new constitution. All of these things, of course, could ultimately prove beneficial for everyday Chileans and help the nation in its advancement toward developed-economy status, but investors worry they will compromise the decades-long commitment to fiscal and financial prudence that always set the country apart from its peers. President Sebastian Pinera has already shocked the business community by trying to appease protesters with pledges to alter the constitution and boost spending.

“Chile’s been the oasis, the calm sea in what’s normally a stormy region,” said Edwin Gutierrez, the head of emerging-market sovereign debt at Aberdeen Asset Management in London. “But now it’s the focus, the trigger-point of the Tsunami.”

In the early hours of this morning the leaders of almost all the parties in Congress agreed to call a plebiscite on whether, and how, to write a new basic charter. That will go a long way toward meeting protesters’ demands. The peso rallied 2.7% to 781.82 per dollar as of 9:10 a.m. New York time, though it’s still down 4.4% this week for the world’s worst performance.

Chile cemented its outsider status in Latin America in the late 1970s and 1980s during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet when a cadre of economists, many trained at the University of Chicago, implemented a series of free-market reforms. They slashed government spending, cut tariffs and privatized utilities, water rights and the pension system. The overhauls eventually put an end to years of instability marked by hyperinflation and unemployment, problems that persisted through the first years of the dictatorship.

By the time the country returned to democracy in 1990, reforms ushered in an economic boom that saw average annual growth of 6% over the next decade. In the 2000s, the country started a sovereign wealth fund -- a rarity for a developing nation.

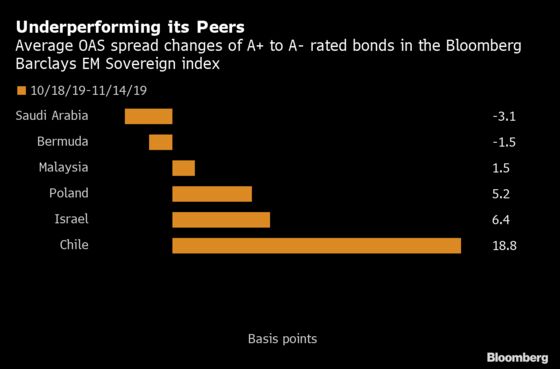

Chile has since boasted one of the best credit ratings among emerging markets. But now, investors’ perception of the risk has skyrocketed. While for years the cost to insure sovereign bonds was the lowest in the region, the price is now just a hair above Panama’s. Though Brazilian stocks are close to a record high, Chile’s benchmark is near a two-year low.

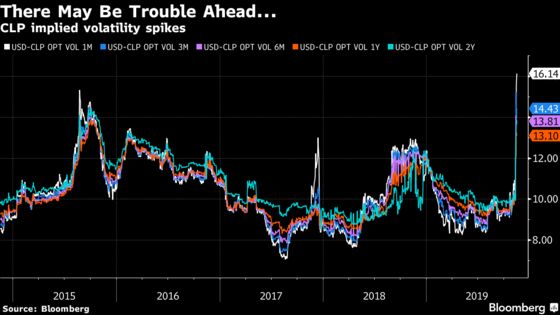

And investors don’t expect the pain to go away anytime soon. Chile’s currency options market shows investors are preparing for a long period of instability as implied volatility soars.

Of course the social turmoil in Chile isn’t happening in isolation. Populist governments have been elected in Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. Venezuela is basically a failed state. Peru’s president recently dissolved Congress after his predecessor was ousted amid corruption allegations. And in Bolivia, enraged supporters of former President Evo Morales are clashing with police as his replacement tries to establish order.

In Chile, there’s broad popular support for reform -- almost three-fourths of those surveyed late last month said protests should continue. What worries analysts isn’t a few quarters of slow growth as the country cleans up the debris from the riots. The real concern is that the economic and social model that has supported 30 years of outperformance may be scrapped.

“It’s true that growth is low,” said Alberto Ramos, the chief Latin American economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. “It’s true that income isn’t high enough, that this is an unequal region, that there’s corruption and impunity, that people feel disenfranchised and unrepresented and with no economic progress.

“But if you go for a short-cut or a populist response you may make a bad situation worse,” he said.

The Chile of the future will likely have a higher tax burden, higher fiscal spending and possibly more debt. An additional threat, given the lack of support for traditional political parties in Chile, is that a new constitution may end up empowering politicians of both the extreme left and right.

“This is not a situation where the government can restore stability by making a few concessions and leaving the framework untouched,” said Patrick Esteruelas, the head of research at Emso Asset Management in New York. “The net result of which is probably a new and permanent risk premium, and a reduction in incentives for corporate investment which should result in structurally lower growth.”

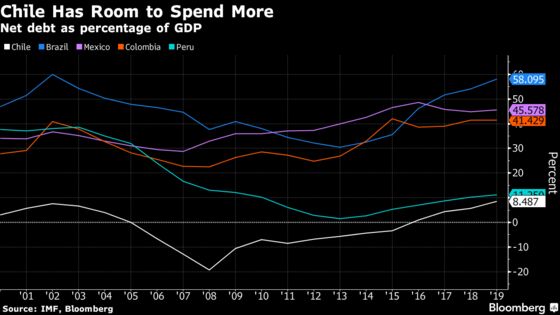

All that said, Chile is well positioned to shift toward higher taxes and increased spending. After racking up huge budget surpluses during the commodities boom, the nation can afford to spend a few more points of gross domestic product on health and pensions. The government spends about 25% of GDP, compared to 38% in Brazil and Argentina.

Inequality is severe. Chile’s top 1% have earned 20%-25% of national income almost every year since 1990, according to a 2018 study published by the World Inequality Database. A 2014 working paper by the International Center for Tax and Development found that Chile’s super rich may have been taking a higher share of wealth than any country in the world.

“If there’s one economy that can afford to have a bit more social spending and fiscal slippage, it’s Chile,” said Aberdeen’s Gutierrez, who helps manage $16 billion of assets. “The years of saving have stood it in good stead. Redistribution is necessary too.”

He’s considering adding more Chilean securities to his portfolio, taking advantage of the recent sell-off to lock in low prices. Until now, Chilean debt just hasn’t paid enough to be attractive.

As an example of how the country has changed, on Nov. 13 the political committee of Pinera’s National Renovation, a center-right party founded by supporters of Pinochet to promote private property and free enterprise, put out a statement urging the government to “spend whatever it takes” to fund health care and student loans while boosting pensions and the minimum wage.

“The dogma of the free market cannot continue to stand in the way of a fairer society, and economic growth and job creation should go hand in hand with social policy,” it said. A month ago such a statement would have been almost unthinkable.

To contact the reporter on this story: Sebastian Boyd in Santiago at sboyd9@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Eric J. Weiner at eweiner12@bloomberg.net, ;David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Brendan Walsh

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.