How Fed Could Decide to ‘Shock and Awe’ With Half-Point Hike

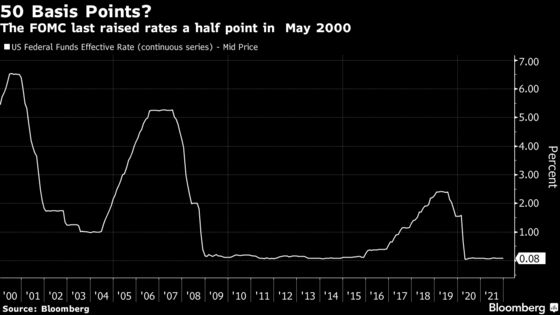

Powell may consider the first half-point interest-rate increase in more than two decades later this year.

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell may consider the first half-point interest-rate increase in more than two decades later this year if he needs a “shock and awe” approach to counter persistently high inflation that risks feeding into Americans’ psychology.

The Fed has penciled March in for its first rate hike since 2018 and is likely to begin with a quarter-point move as part of its usual caution as it begins to remove monetary stimulus. But Powell’s determination to fight inflation could include bolder action if he concludes they are far behind the curve and need to counter a persistent regime of higher prices.

“The bar is very high for doing 50 basis points in March, as the Fed tends to be more careful at the beginning of a hike cycle,” said Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont Securities. For “later in the year, they would have to believe that inflation is much worse than they currently believe -- perhaps if the monthly readings are accelerating.”

The vast majority of economists forecast the Fed will make a quarter-point move in March, though Nomura Holdings Inc. changed its call and now expects a 50 basis-point increase, citing Powell’s hawkish press conference on Wednesday. Pressed on how quickly the Fed would move, he left the door open to going faster than in the last tightening cycle by highlighting the much stronger labor market and much higher inflation facing officials this time around.

Investors are now pricing in about 30 basis points of tightening for the March 15-16 meeting, reflecting a roughly one-in-five chance of a half-point move.

“There is a little bit of shock and awe to 50 basis points,” said Nomura analyst Robert Dent, who viewed the decision as a close call. “Powell more than any other chairman has stressed clean, careful communications with the public. The sense that Americans are losing faith in their inflation fighting would push them to move to show they are taking this very seriously,” he said.

Officials get more evidence between now and their next meeting, including consumer prices for January and February, plus fourth quarter employment costs on Friday. The employment cost index is expected to show a gain nearly on par with the record increase in the prior three months.

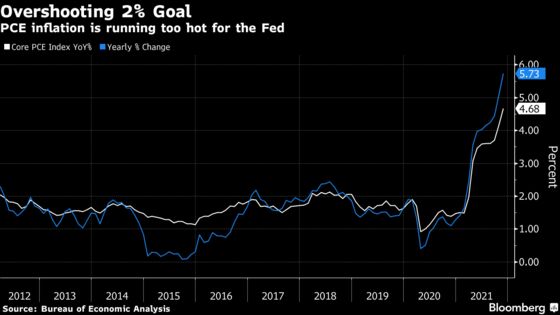

Powell and his colleagues are confronting 7% inflation, the highest since 1982. While supply disruptions associated with Covid-19 are expected to eventually reverse and lower price gains this year, Powell said December’s inflation was worse than expected.

“Going 50 basis points out of the gate requires even stronger evidence that they are behind the curve,” said Ethan Harris, head of global economics research at Bank of America Corp.. “A more likely way to get tough is to quickly shift to hiking at every meeting. If they still feel behind the curve after pursuing that approach, 50 basis points would be on the table.”

Powell, asked about a half-point move, stressed that the U.S. faces a much different economic situation than its last rate-hiking cycle with inflation running far above 2% and an historically tight labor market and unemployment below 4%.

What Bloomberg Economists Say

“There’s upside risk to the four rate hikes priced in by financial markets ahead of the meeting. Bloomberg Economics forecast earlier this month the year will probably end with a total of five hikes, with an upside risk for six.”

-- Anna Wong, Yelena Shulyatyeva, Andrew Husby and Eliza Winger

“We fully appreciate that this is a different situation,” Powell said, adding that in terms of a 50 basis points move, “we really have not addressed those questions, and we’ll begin to address them as we - as we move into the March meeting and meetings after that.”

In May 2000, the Fed under then-Chairman Alan Greenspan raised rates a half point to help reduce too much demand “which could foster inflationary imbalances” – even as inflation was tracking a little above 2%.

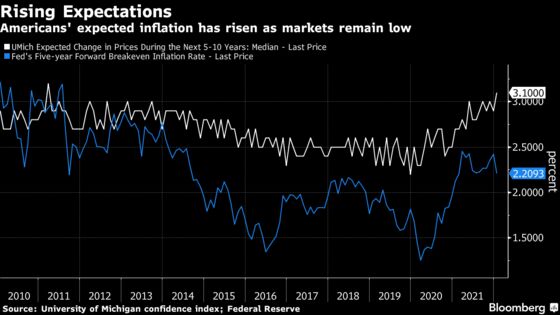

Economists who are gaming out what could bringing about a big hike say the exact set of data that would move policy makers isn’t clear, but Fed officials would need to conclude that persistent inflation was feeding into a wage-price cycle and longer-term inflation expectations.

Inflation expectations in five to 10 years time have crept up to 3.1% among consumers surveyed by the University of Michigan -- the highest in more than a decade. But readings from a market-based gauge which measures five-year inflation expectations beginning five years from now are a more moderate 2.21%, which is very close to its 10-year average.

A big hike might be needed “if they felt they needed to send a message, most likely if inflation expectations appeared to be getting out of hand,” said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Fed officials have tended to favor gradualism. Governor Christopher Waller, in a Bloomberg Television interview earlier this month, pushed back against a March half-point hike. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard has argued that small moves can add up over time. “Shock and awe is almost never a good way to proceed,” he said in a speech in 2010.

“For the Fed to move 50 basis points, I really think they need much more evidence that inflation is accelerating and moving even higher as we get into the spring,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.