How Global Trade Pacts Award ‘Subsidies’ for Climate Pollution

How Global Trade Pacts Award ‘Subsidies’ for Climate Pollution

(Bloomberg) -- While nations have been haggling over climate goals and companies committing to carbon-dioxide cuts, the global trade system has been pushing in the opposite direction.

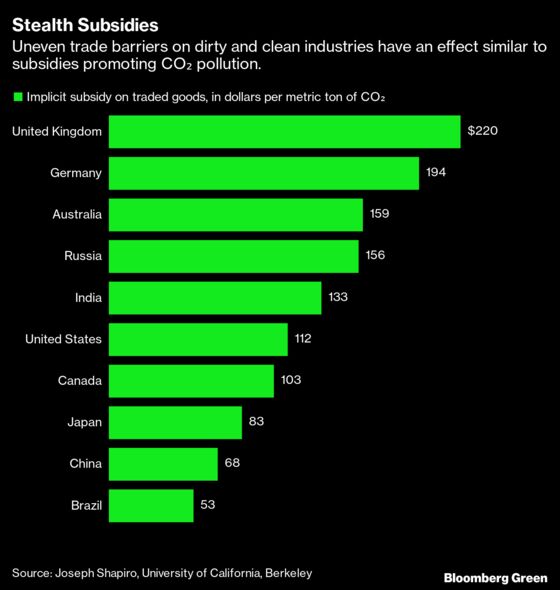

Tariffs and other barriers are providing indirect subsidies to fossil fuel, according to new research covering 163 industries in 48 countries. Joseph Shapiro, the University of California, Berkeley, economist who conducted the work, terms this an “environmental bias” that hasn’t been measured in the trade system. He found it was worth between $550 billion and $800 billion a year—more than direct subsidies such as tax incentives paid by governments to big emitters in 2007.

“This research is pointing out that different sets of policies that seem completely separate—trade policy and climate change—are connected quite closely in ways people might not have noticed,” Shapiro said in an interview.

It’s an accident that makes unfortunate sense given how goods move around the world. There are two things that are happening in parallel, Shapiro found.

First, global supply chains start out carbon-heavy, as factories process raw materials into steel, plastic, aluminum or other commodities. Then, manufacturing those materials further into consumer goods requires less energy and more diverse skills. As a result, later-stage or “downstream” manufacturing is intrinsically cleaner than “upstream” activities like ore-processing.

The second trend causing what Shapiro calls an environmental bias has to do with how tariffs and other barriers emerge. Companies want no or low trade barriers on the raw materials they need because it helps keep their costs down. Later, when they’ve made their products, they then advocate for trade protection, because it keeps their prices relatively attractive to their customers. (There’s also an economic efficiency reason: The earlier that tariffs are introduced into a supply chain, the greater the distortions they create in prices as goods move toward consumers.)

When these trends are combined, they produce the effect that Shapiro writes about. “Upstream” industries tend to be heavy energy users facing low trade barriers. “Downstream” industries, closer to consumers, have lighter CO₂ footprints and, perversely given climate change, higher tariffs.

Katheryn Russ, an economist at University of California, Davis, appeared with Shapiro at a November climate conference at the University of San Francisco. She suggested as a next step that researchers look at nations’ increasing efforts to raise barriers, particularly on key metals such as steel. “I wish that people had thought to do this long before,” she said of Shapiro’s work.

One fix to the problem, Shapiro says, would ensure that trade agreements treat dirtier upstream and cleaner downstream industries the same way, either by increasing tariffs on the former or decreasing them on the latter. Doing so might make strange bedfellows of heavy industry and environmentalists. Now, climate activists pressing for CO₂ reductions in trade would basically be asking governments for the same thing as businesses lobbying for a tariff system that didn’t treat high- and low-polluting differently.

Leveling out the implicit subsidies could reduce CO₂ pollution by more than even large-scale climate policies, such as the EU Emissions Trading System, Shapiro found. U.S. economists commonly have suggested that a reasonable tax on CO₂ emissions might cost polluters $40 a ton. The effects of trade policies, according to Shapiro’s research, is equivalent to giving polluters between $85 and $120 for every ton of CO₂ emitted.

Climate change policy and trade policy have lived separate lives, until now. Shapiro believes that his research may help lead climate policymakers to take greater notice of the hidden effects of trade agreements on pollution.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.