How Blind Spots With Melbourne’s Migrants Sparked Virus Crisis

How Blind Spots With Melbourne’s Migrants Sparked Virus Crisis

(Bloomberg) --

For months, Girmay Mengesha has been an unofficial translator and health adviser in the public-housing tower he shares with hundreds of migrants in Melbourne.

The Ethiopian-born immigrant jumped into the informal role when he noticed most Covid-19 information was in English, rather than the 10 different languages spoken in his block.

“Our people were scared,” the 30-year-old said. “The lack of information meant we had to improvise.”

Infections in Australia’s second-largest city have spiked to a record, just weeks after they were seemingly in retreat, and some of the blame takes aim at how critical information is communicated to migrants in a town that boasts it’s one of the world’s most multicultural. The crisis prompted the Victoria state government to block 3,000 residents of public housing estates, including Mengesha’s, from leaving home for about a week while banning all but essential travel for six weeks in the city of 5 million.

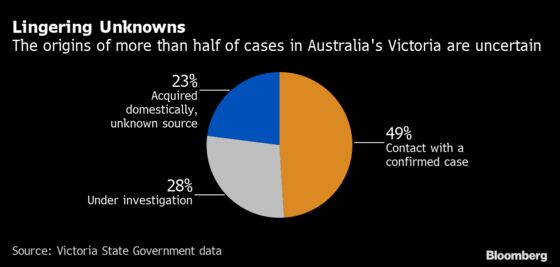

The coronavirus resurgence has also exposed a troubling reality: testing and tracing methods aren’t working as they should, in part because they haven’t been well-designed for the most vulnerable segments of Melbourne society.

Victoria’s daily testing rates were among the world’s best in late May and showed a positive result rate of just 0.4%, the lowest among Australian states. This conveyed a false sense of security, even as the virus was quietly seeding across communities that appear to have been under-represented in testing.

Lengthy waiting times at testing stations may have resulted in a higher share of wealthier people in the data, with many poorer workers who depend on hourly wages unable to stand in line for an extended time.

“They’re doing a lot of testing of asymptomatic people. I’m not sure of the value of that,” Peter Collignon, an infectious diseases physician and professor of clinical medicine at the Australian National University Medical School, said. “It can almost give you a false sense of security.”

Australia is not alone in seeing the poorer parts of society disproportionately hit. Singapore, once lauded as a shining example for its containment efforts, saw cases surge in its migrant worker community, catapulting the tiny city-nation to become one of Asia’s most-infected while the poor have been among the worst affected by new outbreaks in Europe.

Testing Blitz

As part of efforts to regain control, Victorian health officials enlisted the army for an ambitious program to test 100,000 people over 10 days earlier this month. But even if the blitz produces better data, the contact tracing system that follows testing has been plagued by shortcomings.

An independent report from the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee revealed that Victorian officials didn’t follow up with close contacts for symptoms, according to The Australian newspaper. The nation’s own contact smartphone tracing app reportedly has yet to pick up a single case of community transmission.

A spokesperson for the Victorian health department said that all positive cases across regional Victoria are interviewed by the state contact tracing team, but that there had been delays with this process in recent days due to “concentrated efforts.”

The outbreak has ignited a push for more innovative strategies, including environment testing that can better flag clusters. ANU’s Collignon argues waste water surveillance, or tapping into sewerage lines to test for the virus, can allow for a highly pinpointed containment approach, without having to rely on individuals volunteering themselves for testing. It’s a technique already being explored in the Netherlands, Spain and France, he said.

The flawed management of Victoria’s quarantine system, which requires all overseas arrivals to isolate for 14 days at a hotel staffed by contractors rather than police, only exacerbated the outbreak. That helped create a tinderbox environment as some security guards brought infections home to their communities in Melbourne’s poorer and more multicultural neighborhoods, where it spread through large family gatherings.

The challenges with testing, lockdown and travel restrictions are exposing a stark gap between Melbourne’s haves and have-nots.

“If those suburbs were entirely populated by white-collar workers who could work from home, then a targeted approach stopping them traveling would be fine,” said Stephen Duckett, health program director at the Grattan Institute think tank and former Secretary of the Australian Health Department. That’s not the case for many public-housing tenants in blue collar jobs who can’t earn an income at home.

Amid an outbreak that’s grown to over 5,000 cases and shows no signs of slowing, Mengesha has started noticing some health information finally being published across multiple languages this week. Traditional greetings such as hugs and kisses have now ceased.

He’s watching as authorities in other parts of the country race to blunt the spread of the virus. “Hopefully they do learn quickly from mistakes,” he said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.