High-Altitude Argentine Winemaker Is Profiting From Peso's Fall

High-Altitude Argentine Winemaker Is Profiting From Peso's Fall

(Bloomberg) -- Two decades after acquiring vineyards in the foothills of the Andes, Swiss multimillionaire Donald Hess is finally turning a profit in Argentina, helped in no small part by the peso’s dramatic collapse.

Seeking expansion beyond his Napa Valley assets, Hess bought Bodega Colome in the picturesque Calchaqui valley in June 2001 to produce wine at up to 3,100 meters (10,170 feet) above sea level. For years, the export-led operation ran at a loss. But there’s been better luck recently, with the peso plunging 78% since President Mauricio Macri took office in December 2015.

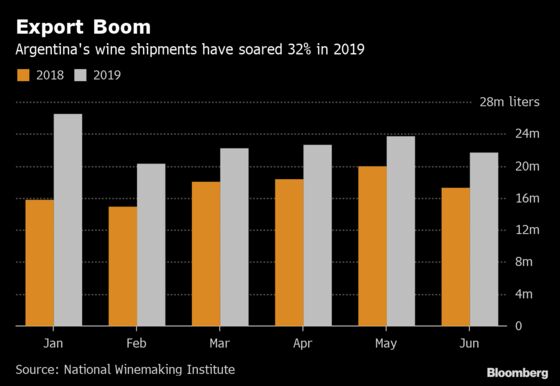

The devaluation has meant soaring revenues for Hess’s Malbec and Torrontes wines, which are largely shipped to the U.S. and Europe. Grupo Colome, which also sells a cheaper brand of wines called Amalaya, is now re-investing the profits and eyeing 5% production growth in the upcoming year, according to Matthieu Naef, who was appointed chief executive officer in April.

“The current exchange rate keeps us pretty calm,” Naef, 42, a Mexico-born veteran of the hospitality and gastronomy industries, said in an interview in Buenos Aires. “The devaluation has allowed us to compensate for rising costs.”

At the same time, Argentina’s wine exporters could soon benefit further from a threat by U.S. President Donald Trump to hit France’s wine industry with tariffs. Trump threatened retaliatory tariffs against France in response to that country’s tax on digital service.

Argentina can trace the start of its wine boom to the late 19th century, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that exports started to flow from winemakers clustered in the western Cuyo region. Today, there are 200,000 hectares (494,000 acres) of vineyards and wine has become as synonymous with Argentina as beef or soccer.

Inflation in Argentina is running at 56%. Winemakers also need plenty of imported parts, from corks to paper labels. With those imports priced in dollars, vineyards that depend on domestic sales, and therefore don’t have dollar-linked revenue, struggle.

Meanwhile, Grupo Colome will export roughly 65% of the 2.1 million bottles of wine it produced in the year ending June. “If we keep exporting 65% to 70%, it’s going to go well,” Naef said.

While the peso’s free float under Macri has benefited wine exporters, a move last year to help achieve fiscal targets by taxing all of Argentina’s exports worked the other way.

Macri says he will scrap the tax at the end of next year. First, however, he has to secure a second term by beating opposition leader Alberto Fernandez in presidential elections on Oct. 27.

Macri believes in export-led growth. Fernandez would probably unwind Macri’s market-oriented reforms.

Exports of Colome and Amalaya go mostly to the U.S. Europe imports the rest, with Germany and the U.K. leading purchases. The wines are mainly made with Argentina’s flagship Malbec variety, an inky red, and the nation’s native Torrontes, an aromatic white.

Naef will spearhead a marketing push for the Amalaya brand, where Grupo Colome is seeing growth among a younger generation of wine drinkers. Because that generation cares more about environmental sustainability, Naef said, he’s pushing for Amalaya’s Malbecs to get organic certification by next year.

“There’s been an awareness shift in wine consumption,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jonathan Gilbert in Buenos Aires at jgilbert63@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: James Attwood at jattwood3@bloomberg.net, Reg Gale, Joe Carroll

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.