Here’s a Way to Help Tell the Good Brokers From the Bad

Here’s a Way to Help Tell the Good Brokers From the Bad

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Don’t be so quick to believe the dirt you hear about brokers.

That’s the inescapable takeaway from research reported by Bloomberg News last week showing that false accusations of broker misconduct are disturbingly common.

Dynamic Securities Analytics, a securities litigation consulting firm, reviewed 82 arbitrated disputes between brokerage firms and their former brokers that took place between 2016 and the first quarter of this year. In roughly half of those cases, arbitrators concluded that firms had defamed brokers when reporting the reasons for their dismissals.

Leaving aside the irreparable damage to the reputations of falsely accused brokers — which is considerable — Dynamic’s research raises serious doubts about the reliability of brokers’ public employment records. Brokerage firms must disclose brokers’ comings and goings and any wrongdoing they commit along the way. That information is meant to allow investors to evaluate brokers’ backgrounds and dodge bad actors.

And if those disclosures are to be believed, then there is an alarming amount of bad behavior. Researchers Mark Egan, Gregor Matvos and Amit Seru reviewed brokers’ employment records dating from 2005 to 2015 for a study in the Journal of Political Economy. They found that 7 percent of brokers have a record of misconduct and that the number exceeds 15 percent at some of the largest brokerage firms.

It’s no wonder financial professionals “are often perceived as dishonest, and consistently rank among the least trustworthy,” as the Capital Ideas Blog of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business said in a post about the study’s findings.

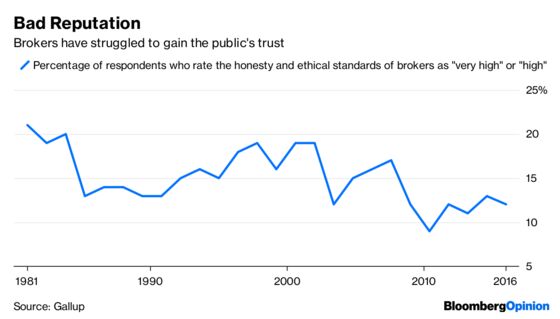

In fact, polling suggests that brokers are particularly ill-regarded. Gallup routinely surveys the public about its perception of honesty and ethical standards among various professions. There have been 26 such polls about stockbrokers stretching back to 1981. On average, just 15 percent of respondents gave stockbrokers a rating of “very high” or “high,” and that number has never exceeded 21 percent.

But there are good reasons to worry that brokers are unfairly maligned. For one, brokerage firms have every incentive to besmirch brokers on their way out. Clients are often more loyal to brokers than the firm. Sowing doubt about a departing broker’s honesty or competence is an effective way to dissuade clients from leaving.

Granted, accusing departing brokers of misconduct reflects poorly on firms, too. But many brokerage firms already have long lists of regulatory and other misdeeds. The financial benefits of retaining clients are likely to outweigh any incremental harm to firms’ reputations.

Also, firms are keenly aware that brokers are often in no position to push back. As Bloomberg News notes, plaintiffs’ lawyers say that most brokers “choose not to expend the time and money it takes to clear their records.” Dale Cebert spent $2 million on legal fees fighting allegations of wrongdoing when he left Morgan Stanley Smith Barney. Few brokers have that kind of money to take on their firms.

There’s a simple way to bolster the credibility of brokers’ records, however: Give every broker the opportunity to challenge allegations of misconduct.

Here’s what I propose. A new legal division of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or Finra, the brokerage industry’s self-regulator that oversees the arbitration process, would appoint a lawyer to represent aggrieved brokers in arbitration. If arbitrators find that the brokerage firm falsely accused the broker, the firm would be required to reimburse Finra for the legal and other costs of representing that broker and pay a nontrivial fine. On the other hand, if arbitrators find that the allegations are valid, the broker would pay Finra a fixed fee of, say, $25,000 — enough to deter frivolous challenges but not so high as to discourage honest ones.

My guess is that the cost to Finra would be offset by the reimbursement and fines it collects. But it should cover any shortfall by raising the fees it fetches from member firms. It would be a small price to pay for the integrity of the industry’s cherished disclosure system.

None of this is to say that there aren’t dishonest brokers, just as there are bad actors in every profession. But if investors are to tell the good ones from the bad, they must first trust the information provided to them. And right now, it isn’t clear what to believe.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.