Hard-to-Trace Virus Cases Emerge from Japan’s Hostess Bars

Hard-to-Trace Virus Cases Emerge from Japan’s Hostess Bars

(Bloomberg) --

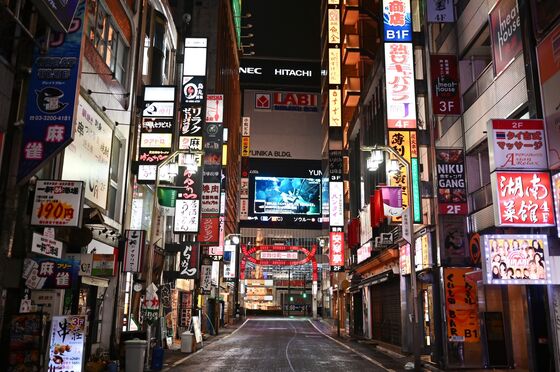

Champagne, chandeliers and glitzy cocktail frocks are all part of the fantasy world conjured up by Japan’s hostess clubs. The coronavirus has delivered an unwelcome dose of reality.

Men can pay thousands of dollars for a couple of hours’ flirtation, with women escorts sitting close and entertaining them. Even as the role of women has changed in Japan, such establishments have endured in the culture. Hostesses -- typically young -- are often treated as “cast members” of these clubs under a professional name, and clients don’t tend to want it known that they’ve spent time there.

An infection cluster connected with Club Charme in the city of Gifu in March confirmed what many in Japan had worried about -- that hostess bars are not only an infection risk but pose special difficulties in contact tracing needed to stamp out clusters of the virus. Figuring out who visited clubs, when they did so and what they did there isn’t easy.

As a result, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike have urged the public to stay away from such establishments. This comes as the number of coronavirus cases surged in the past week, with Tokyo confirming 201 cases Friday, a daily record. Many hostess clubs are closing their doors, putting thousands of women out of work -- at least temporarily -- at a time when they face more difficulty than usual finding other jobs. Some have raised concerns that hostesses could turn to the illicit sex trade.

While red-light districts all over the world are facing similar woes, Japan’s hostess clubs have a more ambiguous role in society, often used for business entertainment. Some successful hostesses compare themselves to geisha, who have a centuries-long tradition of entertaining guests at parties with music, dancing and conversation.

Akemi Mochizuki said she decided to shutter her four clubs on April 1 in the popular entertainment district of Ginza, affecting about 100 hostesses.

The number of customers had dwindled in February, she said, after Japanese companies increasingly told employees they could no longer claim entertainment at the clubs as a business expense, a typical practice. She kept going for a while after being unnerved by the news from Spain and Italy, relying on improved ventilation and other hygiene measures.

“I thought it would be better to shut down earlier, but the women who work here didn’t want to close,” she said in an interview. “So I was in a dilemma.”

It’s been tough to track the coronavirus infection in urban areas of Japan, one of the factors cited by the government in declaring an emergency for Tokyo and six other prefectures on April 7. More than 40% of those infected in Tokyo in the week that ended April 12 couldn’t be traced, according to a report released by the city. Confirmed cases in Tokyo have surpassed 2,500 this week from about 100 a month ago. Abe Thursday said he would expand the state of emergency across the country.

From a prevention standpoint, it would have been better for the government to shut the clubs down quickly, while guaranteeing compensation, Mochizuki said. Enforcing a shutdown is not technically possible even under an emergency declaration in Japan.

Risky Work

The nature of the work in such clubs involves face-to-face interaction in tight quarters, something virus experts have said is particularly risky. Wearing a mask isn’t an option for the women working there.

While those who run hostess bars say they provide clients with nothing more than drinks and conversation, they are required to register with the police under a law controlling “amusement businesses.” It’s a separate category from those offering sexual services. Yet even this category has a tainted image, meaning banks often won’t lend to them and the government won’t provide subsidies, Mochizuki said.

“People associate hostess clubs with gangsters,” said Kaori Kohga, who heads an industry association representing hostesses and clubs. “We are operating legitimately, so I don’t know why we all get tarred with the same brush.”

That image has also made it difficult to trace cases from the clubs, said Nobuo Murakami, a professor at Gifu University Hospital who is advising the region’s cluster response team.

Unlike gyms and other businesses where virus clusters have been reported, hostess clubs don’t tend to keep lists of who has visited -- privacy is part of the draw. Some known to have visited clubs have responded angrily when contacted, and refused to be tested, he said.

“I understand people may not want it known that they went to Club Charme, but if the infection spreads from here, it may lead to someone dying,” he said.

According to a local media report, 33 people connected with Club Charme have been confirmed as infected with the virus. Similar clusters have emerged in Osaka and Shimane prefecture, according to domestic media.

Many of Mochizuki’s Ginza hostesses, who are self employed, have gone to stay with their families to save money, she said. Others remain in Tokyo in tiny apartments with no work, yet may be denied access to benefits the government is providing to workers amid the pandemic.

Entertainment Industry

Japan’s hostess industry covers a broad range of businesses. There are almost 7,000 in Tokyo, stretching from the eye-poppingly expensive clubs in Ginza to the cheaper bars and cabaret clubs that exist in almost every community -- even on remote islands. Kohga is worried that financial need could force hostesses, especially those from the less exclusive end of the market in Kabukicho, to turn to the illicit sex trade.

Following an outcry, the Ministry of Health reversed course this month to allow hostesses and sex workers to claim benefits made available to those who had to stop work because of school closures. But the bars themselves may not be able to claim small business subsidies, which have been limited to those that focus mainly on serving food.

Some of the larger, more prominent clubs are adopting video-conferencing in a bid to keep clients loyal even without physical interaction, according to Kohga.

It may be difficult for them to recreate over Skype or Zoom what Mochizuki describes as a dream-like atmosphere that keeps clients coming back, despite often paying 300,000 yen ($2,780) or more a visit.

“It’s like performing on a stage,” she said of her work. “I think it helps to think of us like geisha. We’re professionals at the art of conversation.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.