German Think Tank and Bane of ECB on Euro's Money Flows Turns 70

German Think Tank and Bane of ECB on Euro's Money Flows Turns 70

(Bloomberg) -- Germany’s most-prestigious economic think tank, and thorn in the side of the European Central Bank, turned 70 this week.

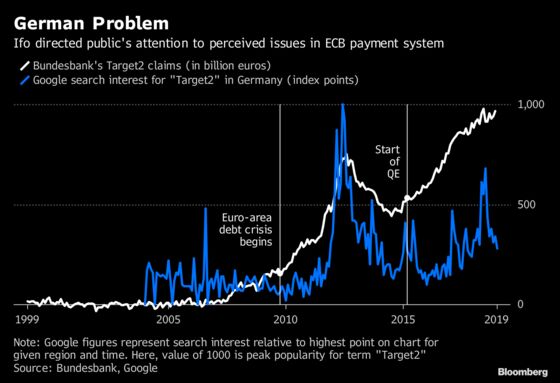

The Munich-based Ifo Institute for Economic Research gained renown during the euro-area debt crisis under the then-leadership of Hans-Werner Sinn. He elevated an obscure measure of ECB bookkeeping into a barometer of Germany’s financial exposure to the bloc’s weakest economies.

To Sinn’s critics, his analysis is both misguided and a key reason for German resistance to the ECB’s crisis-solving actions, as well as wider resentment against the central bank itself. To his fans -- mostly in Germany but also in like-minded nations such as Austria and the Netherlands -- he’s shining a light on risks that would ultimately be borne by the bloc’s thriftiest taxpayers.

The debate over a measure of payment flows known as Target2 quieted down for a while after Sinn handed the baton to Clemens Fuest in 2016, and as Europe’s economy regained momentum after its double-dip recession. But it stayed alive, and resurged last year when the Bundesbank’s Target2 balance approached 1 trillion euros ($1.1 trillion) -- the amount Sinn’s defenders see at risk in the event of a break-up of the euro zone.

Ifo holds particular power over public opinion as it advises the government, publishes Europe’s most-important gauge of business sentiment, and is regularly quoted in the mainstream media. It’s a responsibility that can’t easily be ignored at a time when populist political factions are openly opposing European integration.

“Ifo’s position under Sinn was marked by fears of Germany’s risks from monetary union,” said Karl Whelan, an economics professor at University College Dublin, who is studying the ECB’s payment system. “When viewed through that prism, Target2 balances could be seen as other nations within the euro zone profiting at Germany’s expense.”

Target2 is essentially a collection of records of money traveling within the euro area as companies and people pay for imported goods and services. The individual country balances that obsess Germany are a result of each of the 19 national central banks compiling their own balance sheets, even though monetary policy is implemented at the European level.

“The Target balances are interest-bearing public loans that are being used to finance current-account deficits.” -- Hans-Werner Sinn, June 2011

The system can certainly offer insights into demand flows and financial stresses, but those balances aren’t loans in the standard sense. There are no repayment dates, schedules, or security required.

In a joint paper with his predecessor in December, Fuest argued that Germany’s high exposure means it’s susceptible to being manipulated if financial systems collapse in other members of the currency bloc.

“We have an obligation to tell the truth, and we have no control over how people use or abuse our results,” he said in a Bloomberg interview. “We don’t want our analysis to be understood as a criticism of the single currency or European integration but it’s not our task to convince everyone that the euro is only good.”

While ECB officials have argued that any country leaving the euro area would need to settle any liabilities, they’ve also said -- with rising impatience -- that any attempts to rein in Target2 would undermine the currency project as a whole.

Economic experts around the world have come under fire in the past decade, first for failing to predict the global financial crisis and then over the consequences of events such as Brexit and Donald Trump’s election as U.S. president. Ifo’s reputation has held up in Germany, but it may have contributed to discontent elsewhere with the German attitude to monetary union.

“Seen from certain parts of Europe, Germany has been very ideological,” said Rosa Balfour, a senior transatlantic fellow at The German Marshall Fund of the United States, who focuses on European policy. “There hasn’t been enough of an effort to understand alternative views with respect to the whole euro-zone crisis -- such as those from Southern Europe -- and perhaps that could’ve been a debate fueled by the country’s think tanks.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Carolynn Look in Frankfurt at clook4@bloomberg.net;Lorcan Roche Kelly in Sixmilebridge at lrochekelly@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Jana Randow

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.