Fraga Warns ‘Combustible’ Situation Brewing in Brazilian Markets

Fraga Warns ‘Combustible’ Situation Brewing in Brazilian Markets

(Bloomberg) -- Arminio Fraga has seen his share of financial crises in his 63 years: “Being an old-timer I have the memories and scars of events like this,” the influential former Brazilian central bank chief says.

And when he looks at Brazil’s finances today, he sees telltale signs that another one could be brewing amid the pandemic. He rattles them off rapid-fire: a tumbling currency, surging inflation expectations and a government scrambling to prevent jittery investors from whisking more money out of the country by cutting back the length of its debt maturities, selling a growing amount of one-day floaters. That debt strategy, in Fraga’s words, buys you time if you are doing something to improve the situation. If not, it’s just procrastinating.

“At some point this is combustible material, this is money in people’s hands,” Fraga, a one-time George Soros protege who runs his own hedge fund in Rio de Janeiro today, said in a video interview Wednesday. “Over 50% of GDP comes due within a year if you include the repos in the central bank balance sheet, which you should. What we’re worried about is how much of this gasoline is in the hands of the public.”

Fraga burnished his credentials as an inflation-slaying crisis fighter back in 1999, when he jacked up benchmark interest rates to 45% on his first day as central bank president in Brasilia. This time, though, its action on the fiscal front, not the monetary front, that’s needed to regain investor confidence, he says.

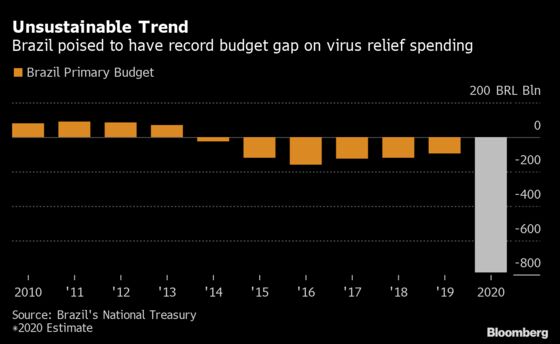

The core of the problem is, once again, an out-of-control budget deficit that Fraga says could reach a record 17% of GDP by the end of the year. But unlike the experience of Latin America’s largest economy in past decades, this time the furious spending was justified: Brazil has ratcheted up social funds to face the economic downfall from the measures to tackle the coronavirus outbreak.

Handing over billions of dollars in emergency cash handouts to informal workers and those who lost their jobs because of the pandemic allowed the government of Jair Bolsonaro to contain an economic and social crisis and even start a faster-than-expected recovery, making the president much more popular along the way.

Yet it’s the prospect of prolonging this massive aid into 2021 in a country with a huge debt what’s flashing red lights to economists and hedge fund managers alike. As things stand now, Brazil simply doesn’t have the money to do so.

It is not by accident then that investors are shunning Brazil despite record liquidity in global markets. The country’s real is by far the worst performing major currency this year, the share of offshore investors in IPOs has collapsed and outflows in foreign portfolio investment are reaching records for the second year in a row. Swap rates have steepened to price in the fiscal deterioration, with traders all but certain the central bank will raise rates from an all-time low 2% in December despite the economy being set to contract more than 5% this year. Fraga says it could happen “soon,” pointing out that a combination of high inflation and recession is nothing new in Brazil.

“There is potential for a crisis. The economy is recovering some, but we don’t know how much of it is due to this money being injected in people’s pockets,” Fraga said. “I don’t see things calming down if we don’t do the basic stuff on the fiscal side, I really don’t.”

Second Anchor

At his hedge fund and private equity firm Gavea Investimentos, Fraga says Brazil’s spending cap rule -- which puts a lid on how much government expenses can increase -- may need to be reviewed. Economy Minister Paulo Guedes has fiercely defended the cap amid pressures to increase social spending, and Fraga admits investors may frown upon the idea at first. But what the former central bank chief proposes is a multi-step plan that would include a further revamp of pensions, overhauls to the country’s over-indulging benefits to civil servants and burdensome tax system, as well as a new budget anchor to achieve a primary surplus in the short to medium term.

Guedes seems at times to be preaching in the desert about the importance of reforms, Fraga says, as Bolsonaro keeps adding obstacles to measures that would impact servants and other pressure groups in the near future. But in the end, none of it will move forward if the executive “doesn’t put it’s weight behind” the overhauls to get them done despite the potential political backlash, he says.

“It seems to political observers that a lot of this is connected to re-election,” Fraga said. Brazil’s next presidential elections are in late 2022. “It’s fine to keep a cap on government spending and investments for another year. But then we need a second anchor on the primary deficit, we need to get rid of that.”

While he remains optimistic that Guedes can get the country back to the right track, he also has pointed out the agenda has largely lost momentum amid municipal elections in November, proposals that were not formatted properly and insisting on ideas that face fierce opposition, such as a tax on financial transactions.

“It’s an obsession. From a macroeconomic point of view it’s a lousy tax; it’s cumulative, it’s regressive,” Fraga said. “Above all, it’s a sneaky tax, as a liberal that I am, I think people ought to know they are paying taxes. I hope mister Guedes gives up this idea, but he seems relentless, sadly.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.