Hurricanes Reveal Just How Resilient an Area Is, or Isn’t

Hurricanes Reveal Just How Resilient an Area Is, or Isn’t

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Two extraordinary tropical storms right now are hitting major population centers in very different parts of the world. Hurricane Florence made landfall Friday morning in North Carolina in the U.S. Typhoon Mangkhut, meanwhile, is headed for the Philippines and on to China’s southern coast, perhaps directly at Hong Kong, where it could be the most powerful storm since records began in the city. In both regions, millions of people who require billions of dollars of infrastructure must prepare for winds, rain, storm surges and rebuilding.

Many residents of the Carolinas have evacuated, which is undeniably a good thing — but evacuation is a response, not a plan. North Carolina in particular has done a poor job of planning for a future of bigger, more moisture-laden storms. Six years ago, the state Legislature ordered state and local agencies to ignore scientific models showing rising sea levels when developing their coastal policies, effectively allowing development in vulnerable areas to continue unchecked. A year later, lawmakers weakened the state’s building codes, removing requirements that would better protect homes in the path of tropical storms. As Bloomberg News noted last year, the federal government has its weaknesses, too, as the Federal Emergency Management Agency still uses flood-risk maps that haven’t been updated since the 1970s.

Hong Kong’s residents can’t really evacuate, and the city’s population is far more densely packed than anywhere Florence will affect. It’s also far better prepared, as a result of policies and infrastructure set in place years ago. A look back at the havoc typhoons wrought on the city shows just how far it has come.

Policies, codes and centralized planning decisions all matter. So, too, does the centralization of infrastructure. Earlier this month, a typhoon hit western Japan and an earthquake hit Hokkaido. In the Kansai region, where the typhoon hit, more than 2 million buildings lost power; Hokkaido lost power completely as three coal-fired power plants generating half of the island’s power, all located very close to the earthquake’s epicenter, failed. In both cases, failures at a handful of points in the power grid caused systemwide faults.

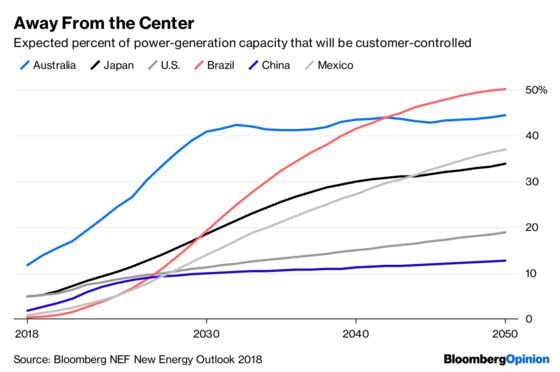

There’s a clear need for more resilient infrastructure in centralized, fault-prone systems — a case Bloomberg NEF has been making since Hurricane Sandy. What our analysis also finds is that on the basis of economics alone, the power systems of many countries will become highly decentralized in coming years. By 2050, more than a third of power-generation capacity in Japan will be customer-controlled in homes and businesses; in Brazil, that figure will be more than half. That decentralization can be a resilience dividend if millions of small generators compensate for a small number of centralized failures.

Decentralization is an economic outcome, based on the cost of energy, but it will inevitably have policy implications and involve policy decisions as well. Decentralization — and the resilience it can bring — distributes costs and benefits, but it doesn’t exempt governments from making smart, forward-looking decisions. Centralized decisions on things like building codes and flood zones can catalyze resilience. Energy will take its economic path to distributed resilience. Policy and planning should take its centralized path to it as well.

Weekend reading

- The U.S. Energy Information Administration takes a look at Hurricane Florence’s disruptions to the Southeast U.S.’s electricity and transport fuels systems.

- Liam Denning says that Tesla Inc. doesn’t need a new operations chief. It needs a new board of directors.

- Aston Martin’s all-electric Rapide E is now under development, and it will join an increasingly crowded field of electric supercars by decade’s end.

- Volkswagen AG gets its days (and weeks, and months) in court as it can’t escape its diesel emissions scandal.

- Michael Liebreich dives into the electrification of transport beyond automobiles — and into commercial aviation, shipping and trains.

- An Uber product manager describes the company’s mission as “building the packet switched network for the physical world.”

- Mohamed El-Erian has nine lessons from the global financial crisis.

- The world’s post-Lehman Brothers legacy? $250 trillion in debt.

- We never learned from Lehman: Ten years after it collapsed, the financial system is still too fragile.

- The automotive industry has more than $51 billion in delinquent debt obligations.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nathaniel Bullard is an energy analyst, covering technology and business model innovation and system-wide resource transitions.

Miho Kurosaki is an energy analyst who covers the power market in Japan and Korea.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.