The Fed Should Take a Sharper Look at Corporate Debt

The Fed Should Take a Sharper Look at Corporate Debt

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The mechanism that normally bails out corporate America in times of trouble may be troubled itself. And that could be a problem when the economy does hit the next downturn.

On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve released its first-ever report on financial stability, which concluded that things are pretty stable. The Fed did raise some concerns about corporate lending, but it’s a pretty tame warning compared with what some have said. The closest the Fed gets to sounding an alarm is noting that unlike in other economic expansions, it is the companies with the lowest credit ratings that have added the most debt. But the report’s authors quickly pivot to a nothing-to-see-here stance. The costs to service that debt, they say, remains historically low even for the “risky firms.”

Despite the Fed’s assessment, some data in the report should give the central bank and others pause. The reason has to do with the way businesses tend to borrow compared with individuals. When sales drop, businesses take out debt to keep the lights on or pay their bills. Individuals do that, too, especially with credit cards, but to a much lesser extent, and that’s more than balanced out by those who either pay down their debt or have it wiped out in bankruptcy. Those things happen for businesses as well, but it takes longer. Banks are also typically slower to cut off corporate credit.

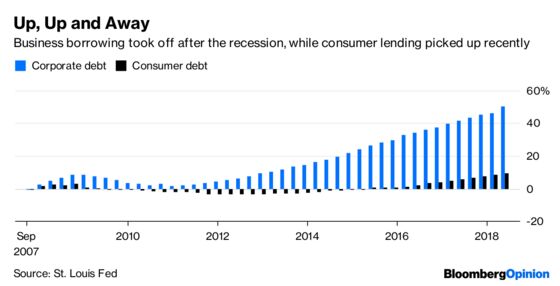

In the first year of the Great Recession, for instance, total business credit, which includes commercial real estate lending and nonprofits, rose nearly 6 percent, or $566 billion. Consumer debt, on the other hand, fell by 1 percent, or $113 billion. Both dropped off pretty significantly in the next year or two after the recession. Before long, though, corporate credit took off again, rising to just more than $14.8 trillion. The portion of that debt that is owed by corporations, not real estate developers or nonprofits, is now nearly $9.5 trillion, or more than 50 percent what it was a decade ago. Consumer debt, on an absolute level at $15.3 trillion, is higher than it was at the peak of the mortgage bubble, but it’s much lower as a percentage of GDP.

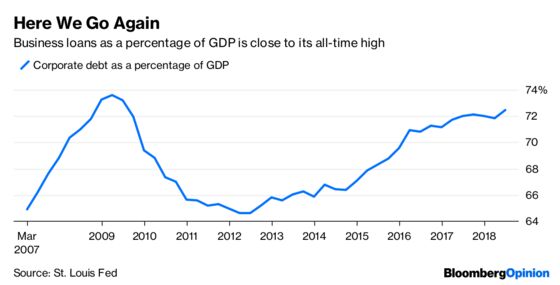

That’s not the case for corporations, which have gone on a borrowing binge over the last few years thanks to rock-bottom interest rates. Business debt as a percentage of GDP is now as high as it has ever been. And the peak last time around came after the recession was over, not before it started. It’s not clear there is enough credit in the system to activate the corporate debt airbag that usually cushions businesses when the economy gets bumpy, especially with interest rates on the rise.

In addition, businesses have tapped around $1 trillion in debt from nonbank lenders, including hedge funds and private equity firms and other investors. While that means banks are less exposed to the riskiest corporate debt than they might have been a decade ago, there is a good chance the so-called shadow banks, which are essentially investment funds, will either blow up or run for cover if the value of corporate credit drops. That means banks will not only have to meet those extra borrowing demands but possibly plug the hole left in the credit system if the shadow banks go dark. And given what happened in the last financial crisis, and stricter regulations that have been put in place since, large banks will most likely close their lending windows pretty quickly.

The Fed may be right to say that the fuse that could cause the next debt bomb hasn’t been lit. But that fuse is starting to look mighty short.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stephen Gandel is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and equity markets. He was previously a deputy digital editor for Fortune and an economics blogger at Time. He has also covered finance and the housing market.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.