Bond Investors Upend Their Portfolios to Greet Fed’s New Reality

Fed’s New Reality Has Bond Buyers Upending Their Portfolios

(Bloomberg) -- Bond investors are struggling to adapt as the Federal Reserve’s emergency actions to combat the pandemic reshape their markets in ways that may be irrevocable.

An uneasy calm took hold Tuesday as traders confronted the astronomical program of quantitative easing unveiled Monday, which commits the U.S. central bank to an unlimited amount of bond purchases to shore up markets. This respite marks a sharp contrast to the reaction just a week ago, when stocks sank and yields spiked despite policy makers slashing rates to zero and rolling out a half-trillion-dollar Treasury purchase program. The new tone suggests the quick fix may be holding, but investors must now navigate a fundamentally altered landscape.

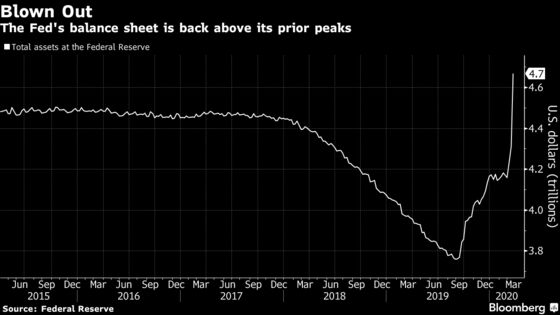

Consider it a radical “new normal,” to adapt the phrase bond giant Pacific Investment Management Co. invoked following the 2008 crisis. Then, it took the Fed seven years to push rates up from zero. The central bank’s balance sheet is larger than it’s ever been, and regulatory changes have recast the role of dealers, who say they’re less able to keep the machinery of markets humming. That’s led some to speculate that the U.S. faces Europe and Japan’s fate: zero rates and low growth for years and years.

“When the dust settles and we look at where we are in terms of the Fed’s balance sheet, interest rates and outright Treasury debt outstanding, it’s going to paint a fairly bleak picture in the long term,” said Bryan Whalen, a portfolio manager at TCW Group. “We’re going to have a lot of work to do as a country to get out of this.”

For TCW, which Whalen said entered the crisis “as defensive as we’ve almost ever been,” that means picking its way carefully back into blown-out credit markets, where spreads are getting attractive but risk remains high. He doesn’t love Treasuries given their low yields, but he favors long-dated bonds, which are buoyed by moribund expectations for growth and inflation and the prospect of the Fed leaving rates at zero for years.

U.S. markets are already pricing in fed funds stuck at zero for at least two years, judging by the overnight indexed swaps rate -- though those contracts aren’t extremely liquid at the moment.

Envision Capital Management’s Marilyn Cohen has been trying to shed lower-quality hotel and airline bonds for the past few weeks, but says it’s hard to get accurate prices. “I’ve been in this business for around 40 years, since 1979, and have lived through a ton of panics and events, but nothing that is this bad because it’s so pervasive,” said the chief executive officer of the bond manager in El Segundo, California. “The good news is that the cavalry -- the Fed -- understands that.”

Looking further ahead, there’s a risk that once the crisis ends, the financial system will be awash with funds but little demand to put them to work. This has been the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan’s struggle for the past decade.

The Fed’s unprecedented efforts to support commercial-paper and credit markets as well as municipalities show how concerned it is about this risk.

Yields surged much of last week, a particularly worrying development to Research Affiliates LLC senior adviser Cam Harvey because it signaled investors liquidated even Treasuries, which are normally a preferred refuge, and shifted to cash, “the ultimate risk-off.”

“The risk that we run is that we are stuck in a Japan-like situation,” said Harvey, also a professor at Duke University and among the first to posit a link between an inverted yield curve and impending recession. “And the problem with a liquidity trap is people just want to hoard cash.”

The Fed’s exit from this brave new policy world is complicated in a market that’s become accustomed to heavy-handed stimulus over the past decade. The central bank may find itself boxed into a corner with easy monetary policy given the ruckus that accompanied earlier attempts to withdraw support. The May 2013 taper tantrum was an extreme example. There was another flare-up in 2018 when the Fed delivered what was to be its last rate hike in the midst of a balance-sheet unwind.

The contention that the U.S. is headed for a liquidity trap gets plenty of pushback, however.

“It’s probably too early to say, but my inclination would be no,” said Brian Kennedy, fixed income portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles & Co. “We’re not at the point where we’re saying it’s a lifelong sentence, we’re going to live here with zero rates.” He’s confident that inflation can pick back up as supply-chain disruptions subside and demand recovers, leading to bottlenecks and price increases.

But it’s hard to see how that translates to a lift-off from the zero bound for U.S. interest rates. The central bank has pledged not to hike its policy rate while inflation remains below-target. This crisis descended as inflation was already more than a decade into missing the Fed’s 2% goal. The market’s expectations for price gains over the next decade have risen from this week’s 11-year low, but are running below 1%.

The response from U.S. lawmakers could be the difference between years of stagnation and a decent recovery. The Treasury’s exchange stabilization fund to backstop all these emergency measures is undercapitalized, and Congress must beef that up a lot, Harvey said.

“The Fed has got a limited number of things that it can do, and it really needs the Treasury,” he said. “It’s very important that the Treasury steps up.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.