Fed Looks Like Just an ‘Average Investor’ After Market Tantrum

Fed Looks Like Just an ‘Average Investor’ After Market Tantrum

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has long promised to be flexible when setting monetary policy. After Wednesday’s performance, many on Wall Street are questioning whether that flexibility means bending over backward to placate jittery financial markets.

At firms from London to Los Angeles, investors and analysts are not mincing words about the significance of the Fed’s decision to stop signaling that more interest-rate increases may be coming. The surprise triggered a rally in stocks, gains in Treasuries and weakness in the dollar -- not dissimilar to what investors were used to when the Fed was deploying its financial crisis-fighting stimulus.

Barclays economist Michael Gapen called it “capitulation” in the face of a volatile market. George Saravelos, head of foreign-exchange research at Deutsche Bank, referred to “regime change,” and Tom di Galoma at Seaport Global Holdings called it “one of the most dovish turnarounds” he’s seen from a Fed chair in his 30-year career.

Powell Put

In trader parlance, the takeaway is a newfound belief in the existence of a so-called “Powell put,” or the notion that turbulence in the equity market would influence the Fed to slow or end its campaign to tighten policy. What’s surprising is that Powell seemed to deny this type of reaction function amid two stock-market corrections since the beginning of 2018 that first sent the S&P 500 down 10 percent and -- after a short-term bounce -- almost 20 percent lower and on the brink of a bear market at the end of last year. But by the time of the this week’s Fed meeting, the market had clawed back about half of that second, bigger swoon, thanks in part to a more-measured message from the central bank’s chair.

“We were shocked at how dovish Powell was, especially since equity markets had calmed from the Fed’s ‘patience’ and ‘flexibility’ message since the December FOMC meeting,” Win Thin, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. in New York, said in a note to clients. “We fear that the Fed has given in too much to the market and its tantrums.”

Under Pressure

There was no shortage of pressure directed at Powell in the lead-up to the Federal Open Market Committee’s first meeting of 2019. President Donald Trump repeatedly criticized the decisions to raise interest rates and shrink a central-bank balance sheet still swollen from asset purchases in the wake of the financial crisis. Financial-world savants, such as hedge-fund titans Stan Druckenmiller and Ray Dalio, did as well.

Powell faced several questions about the criticism from the president and the role that the stock market played in his dovish turn. While he did not go so far as to admit the existence of a Fed “put,” he did acknowledge that tightening financial conditions were an important factor in the commitee’s decisions. So were uncertainties about the potential effects on the economy from things like the trade war, the government shutdown and Brexit.

“Financial conditions matter,” Powell said at the post-meeting press conference. “Broad financial conditions changing over a sustained period, that has implications for the macro economy. It does.”

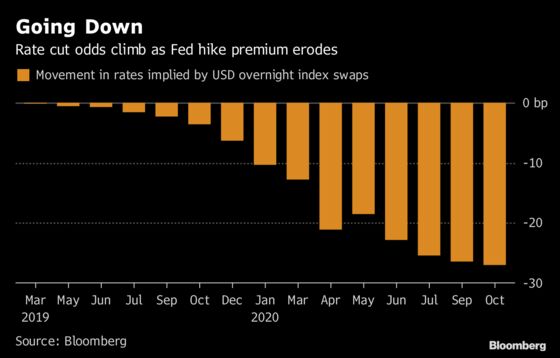

Still, the removal from the FOMC statement of a reference to “further gradual increases” in rates leaves many wondering if the next move by the Fed will actually be a cut. Another surprise for many Fed watchers was the announcement that the central bank was rethinking its plans to gradually shrink its balance sheet by not reinvesting proceeds from maturing securities, a program Powell only last month said was on autopilot.

Markets were calling the Fed’s bluff before this meeting, with fed funds futures pricing in less than a 25 basis point hike by the end of the year as of Tuesday. They have now priced out any chance of a rate increase this year, and a full 25 basis point cut is seen as early as July 2020.

“To me that’s not being data dependent. We don’t have enough data to say for sure we won’t need more hikes,” said Thomas Graff, head of fixed-income at Brown Advisory, which manages $5.5 billion in assets. “I was pretty surprised Powell was that strident in being so dovish that now the market thinks there is no chance of additional hikes.”

Data Independent

The notion that Fed policy was data dependent is gone, said Saravelos, the London-based head of foreign-exchange research for Deutsche Bank.

“Gone are the days of focusing on the unemployment rate,” he wrote in a note to clients. “Gone are the days of balancing risks of going too quick versus slow. The Fed is in data-independence mode unless and until inflation rears its head.”

There’s a real risk that the Fed is being too dovish given the state of the economy, said Brown Brothers Harriman’s Thin, who anticipates further volatility and swings in investor sentiment if that proves to be the case. Even a strong employment report Friday could cause a turnaround in stocks and the dollar, he wrote.

Laird Landmann, co-director of fixed income at Los Angeles-based TCW Group, compared the Fed to an “average investor” reacting to recent disappointing economic data. Needless to say, that’s not exactly a compliment in the investing world.

“Average investors react hyperbolically to near-term data and they don’t understand that high-frequency data has a lot of volatility to it, and to discern a trend you have to watch it for a while,” he said. “You didn’t need to trip all over yourself at this meeting to be so dovish. You could’ve done a gradual transition and truly watched the data.”

Not everyone is critical of Powell’s turnaround. For equity investors, the Fed’s shift delivered a jolt to risk appetite just when it looked like the stock market’s rebound from December’s plunge was running out of steam.

“As the Fed is becoming more dovish, it is breathing life back into certain parts of the equity markets that were more cyclical in nature,” said Matthew Miskin, a market strategist at John Hancock Investments in Boston. “It does suggest that this economic cycle may have a further way to go.”

--With assistance from Emily Barrett, Liz Capo McCormick, Edward Bolingbroke and Reade Pickert.

To contact the reporter on this story: Michael P. Regan in New York at mregan12@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jenny Paris at jparis20@bloomberg.net, Boris Korby

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.