Ex-Offenders Get a Second Look in a Tight U.S. Labor Market

Ex-Offenders Get a Second Look in a Tight U.S. Labor Market

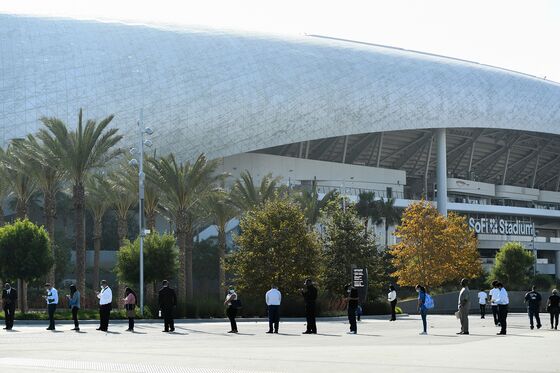

(Bloomberg) -- As companies struggle to find workers in a labor market disrupted by the pandemic, there are signs that the competition for talent is benefiting an often-sidelined group: the estimated one in three U.S. adults who have a criminal record.

Job boards aimed at this population say they are getting busier. One such marketplace, Honest Jobs, had 158 companies register for its site from May to July, roughly doubling its ranks of active employers. New York City-based nonprofit Fortune Society says placements in April through June were up 14% from the same period last year. Another agency, 70 Million Jobs, says it has had to turn away business from those looking to hire.

“There are companies that had no pre-existing program or intentional process for tapping into this demographic, and now we are helping them hire,” said Harley Blakeman, chief executive officer of Honest Jobs.

A more favorable job market for ex-offenders would represent a pendulum swing from the beginning of the public-health crisis, when they were sometimes among the first to lose work amid widespread layoffs. But now, many companies are scrambling to staff their stores, restaurants and warehouses to meet pent-up demand, forcing them to cast a wider net.

Help Wanted

Corporate America is trying a myriad of tactics to address worker shortages, including hosting national hiring events, offering tuition reimbursement and paying higher wages.

Already, restaurant chains like Papa John’s International Inc. are enticing new recruits with bonuses. Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc. is boosting its wage floor in the U.S. to $15 per hour after rival CVS Health Corp. said it would do the same. Amazon.com Inc. is getting creative in addressing its driver shortage by urging delivery partners to advertise that they don’t screen employees for marijuana use.

Smaller businesses have also had to shake up hiring. Of the 100 or so people employed by CleanTurn, an Ohio-based provider of cleaning and disinfecting services, about 90 have been incarcerated, said founder John Rush. While his business has always accepted workers with criminal records, labor shortages have pushed the company to give greater consideration to applicants with violent and sex-based offenses, he said.

“That’s allowed us to be able to say ‘yes’ to more folks who have, on paper, more significantly challenging backgrounds,” Rush said.

Because of the labor crunch, Rush said he’s hired double the number of people with violent and sex-based offenses this year compared to the previous two years combined. Currently, about 10% of his workforce fall under that category.

Still, it isn’t clear how long companies’ more aggressive courtship of workers will last. Enhanced unemployment benefits that were part of the federal pandemic-relief package have expired, which could put some one-time laborers back on the hunt for jobs. The return of in-person schooling might nudge some parents to return to the workplace.

Meanwhile, a weak August jobs report suggests the spread of the delta variant is threatening a robust economic recovery.

A Second Chance

The impact of incarceration rarely ends after a prison sentence is completed. Employers are often unwilling or hesitant to hire those with criminal records, which helps explain why some 45% of formerly imprisoned people report no earnings for the first year after their release, according to a Brookings Institution study.

That was the case for Devine Lambert, who found it extremely difficult to line up a job after being released from jail in July 2020.

“There are actually people who want to work,” said Lambert, 24, who served six months for grand theft. “And we don’t get opportunities to do that because we’re being judged off something we did when we didn’t have a chance.”

Lambert was finally able to secure a housekeeping position at a Los Angeles-area hotel in July, concluding a yearlong search.

Because job offers are so few and far between, workers with criminal records are often forced to settle for temporary, part-time or under-the-table work. Local laws might restrict their access to occupational licenses and other credentials. Public-policy experts say their struggle to get hired often reflects public perception and racial bias.

“Many of these restrictions have nothing to do with the ability to do the job,” said ReNika Moore, director of the ACLU’s Racial Justice Program. “And they are particularly harmful to Black and brown communities, who are over-policed.”

Disparities within the judicial system are especially stark for Black Americans, who make up 40% of the incarcerated population despite comprising 13% of U.S residents.

Lambert landed her job amid highly unusual dynamics in the U.S. labor market. Employers are trying to fill a record number of openings as many people opt not to rejoin the workforce due to a complicated mix of pandemic-related factors. That challenge comes as many companies were already rethinking hiring policies in the wake of a national reckoning on systemic racism that came about after the murder of George Floyd last year.

One example of that shift is CEO Action for Diversity & Inclusion, a commitment supported by leaders of companies ranging from Bank of America Corp. to Goodwill Industries International Inc. The pledge has seen its signatories more than double since May 2020.

“We’re not only giving someone a great opportunity to move forward in their life, we’re giving ourselves the opportunity to learn about the world and to create a richer work environment,” said Steve Preston, CEO of Goodwill, which provides job-placement assistance for formerly incarcerated people.

Gaining Momentum

Even if the labor market soon gets more competitive, ex-offender job applicants may see brighter employment prospects thanks to momentum around clean slate laws, which automatically expunge or seal eligible arrest and conviction records.

Several states have already adopted automatic record-clearing laws and similar legislation is advancing in others, according to Clean Slate Initiative’s state tracker. While most states currently have a petition-based expungement process, it’s typically so complicated and expensive that few who are eligible for relief actually obtain it, Clean Slate’s Executive Director Sheena Meade said.

Similarly, many states have adopted “ban the box” policies, which remove conviction and arrest history questions from job applications and delay background checks until later in the hiring process. At the federal level, ban the box legislation was introduced by Democratic Representatives Maxine Waters and David Trone in March.

While these laws can help change the playing field, job options for those with criminal records still depend heavily on individual companies’ priorities. Meade points to the work of business leaders such as Fifth Third Bank executive Jeff Korzenik, author of “Untapped Talent: How Second Chance Hiring Works for Your Business and the Community,” and JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s Jamie Dimon, who has spoken out in favor of fair-chance hiring, as a sign of a turning tide.

Still, their viewpoints are hardly universal. A 2021 survey by the Society for Human Resource Management found that only a little over half of human-resources professionals said they would be willing to hire individuals with criminal records. Richard Bronson, CEO of 70 Million Jobs, says that his company is receiving a “surprising” amount of inquiries from the tech industry, though he added “they talk a good game, but rarely follow through.”

“Most of the interest that we’ve received in accessing this huge pool of largely ignored talent was driven not by corporate responsibility but out of economic desperation,” Bronson said. “Which is fine because we seek to meet that demand.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.