Europe’s Model of Stability Is Hiding a Major Weakness

Europe’s Model of Stability Is Hiding a Major Weakness

(Bloomberg) -- Luxury hotels in marble palaces, high-end boutiques and bustling street cafes give visitors to downtown Lisbon a sense of how far Portugal has come since it teetered on the verge of default only eight years ago.

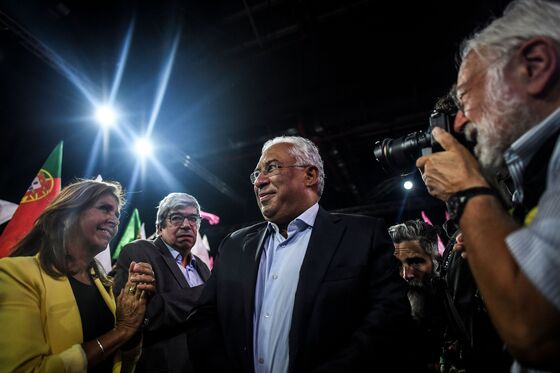

Voters go to the polls for Sunday’s general election on the back of five consecutive years of growth that have seen unemployment halved and deficit spending all but eliminated. Next to the populism and factionalism plaguing neighbors like Spain and Italy, Portugal looks like an island of stability.

But there’s also a fragility to the country’s success and a nagging sense that Socialist Prime Minister Antonio Costa may not have done all he might have during four years of central bank largesse to prepare the country for the next downturn.

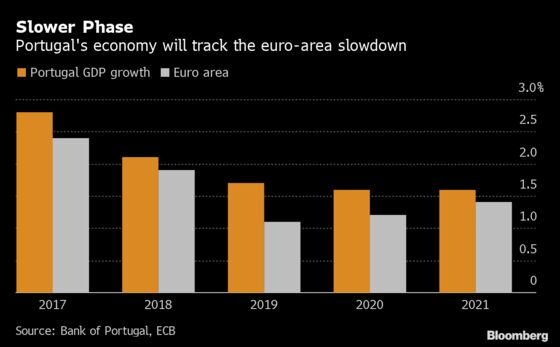

Growth is slowing and the tax take has reached a long-time high for Portugal of 35% of GDP. Costa wants to continue reversing the income tax increases imposed during the bailout. That leaves little room to maneuver on public debt that nearly doubled over the past decade in nominal terms and stood at 122% of GDP last year.

“In a crisis, it’s always the small, vulnerable countries that are hit,” said Arne Rasmussen, head of fixed income research at Danske Bank in Copenhagen. “It doesn’t look like it now, but if for some reason you get some uncertain political picture or growth slows more than expected, people might get nervous.”

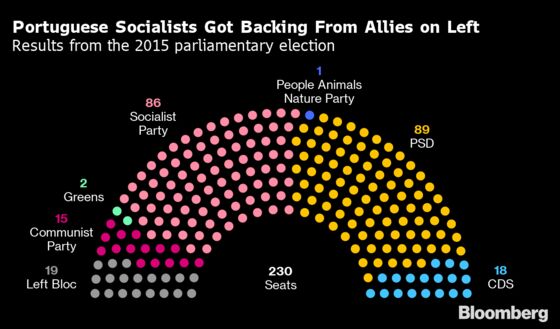

Costa initially spooked investors and European officials when he came to power in late 2015 by reversing some of the terms of Portugal’s 2011 bailout. He has since won their approval, with a sharp reduction in the budget deficit, from near-default levels of 11% in 2010 to a projected 0.2% this year.

S&P Global Ratings last month raised the outlook on Portugal’s BBB rating to positive from stable while investors have pushed 10-year bond yields down to 0.2% down from a whopping 18% in 2012.

Opinion polls suggest that voters will offer their endorsement too and award the 58-year-old another mandate.

All the same, there are mixed feelings on the streets of Lisbon.

“Half of the country says things are better, half the country says it’s worse,” says Joao Marcos Marchante, a 34 year-old partner and producer at Nebula, an animation studio. “The sense I have is that a very large flow of money and people came to Portugal, and this has made everything more expensive.”

Many residents of the capital got squeezed out of their neighborhoods when their wages failed to keep up with runaway rental costs, said Antonio Machado, director of the Association of Lisbon Tenants, which offers legal advice to members.

Portuguese property prices increased 9.2% in the first quarter of the year alone. By contrast, average wages are the fourth-lowest in the OECD, and many of the new jobs pay minimum monthly salaries of 600 euros.

“The tourism and real estate sectors are doing great and many people are benefiting from that,” said Ricardo Silva, a 43-year old waiter serving hot dogs from a kiosk outside the Cartier building on the city’s main drag, Avenida da Liberdade. “We just need most of the other sectors of the economy to improve for the country to become more sustainable.”

Critics say Costa has done too little to boost the country’s efficiency, cut red tape, and down-size a bloated state sector. That’s deterring developers who could help tame the raging property boom by increasing supply.

"Licences in Lisbon are taking a crazy amount of time," said Claude Kandiyoti, CEO of Krest Real Estate Investments, a Belgian company that has invested almost 100 million euros in the real estate sector in Portugal. “It’s a very big concern that can turn a foreign investor away.”

Portuguese companies remain highly leveraged with corporate debt, excluding banks, at about 126% of GDP. Bank profitability is low and non-preforming loans are still at 8.9%. Some civil servants continue to enjoy perks the private sector doesn’t, adding to the tax payer burden.

“They raise salaries of people who shouldn’t get those raises, people in the office,” said Antonio Proenca in Barreiro, a town 25 minutes by ferry from Lisbon that has seen many new commuters set up home in recent years. His salary as a seaman increased “a little” he said, in the past five years.

The center-right party PSD led by Rui Rio says broad tax cuts, including for companies, are the way to kick-start an economy that’s stifled by the tax burden.

“The Socialist Party wants to continue spending on the state,” said Joaquim Sarmento, a spokesman for economic and financial affairs at PSD. “From what we’ve seen in the last four years, that doesn’t necessarily make it better and more efficient.”

Costa has his own ambitions for his second term—fighting inequality and further increasing the minimum wage, all while sticking to fiscal discipline.

Where he’s less ambitious, is on the policy reforms required to make Portugal’s expansion more resilient.

Even if he were to exceed pollsters’ projections and win an absolute majority, the prime minister would shun more aggressive efforts to upgrade the economy, said Antonio Barroso, deputy director of research at political risk adviser Teneo in London.

“He will continue to steer a centrist course,” Barroso said. “Big reforms seem to be off the agenda.”

--With assistance from Samuel Dodge.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Raymond Colitt at rcolitt@bloomberg.net, Ben Sills

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.