Europe Inches Toward a $2.2 Trillion Plan That May Never Happen

Europe Inches Toward a $2.2 Trillion Plan That May Never Happen

(Bloomberg) --

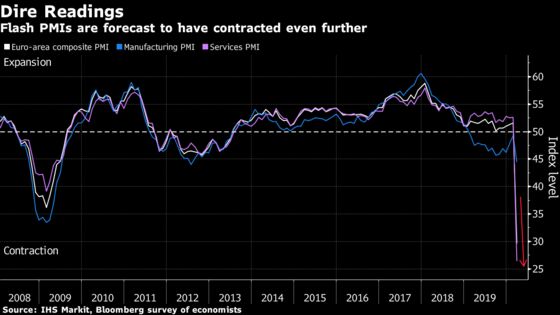

More than 100,000 people are dead, the euro area is headed for its deepest ever recession -- and Europe’s leaders are still talking about what to do.

It’s a strange way to tackle their worst emergency since World War II when it’s already been going on for a couple of months. But in the European Union it seems it can’t be any other way. Even a 2 trillion-euro ($2.2 trillion) recovery plan drawn up by the bloc’s civil service may take months before it sees the light of day. If it does at all.

While such a way of operating seems baffling to those more used to watching individual governments at work, European insiders insist it’s all part of a necessary process. The national leaders who will hold a videoconference Thursday afternoon have conflicting priorities and, in many cases, voters ready to give them a kicking if they’re seen giving away too much, however noble the cause.

And yet, it’s a riddle that all of them have to find a common way to solve -- whether you are Mark Rutte of the fiscally conservative Netherlands or Giuseppe Conte of heavily indebted Italy, or even Viktor Orban, who has restricted democratic freedom in Hungary.

So it’s no surprise that two months and four virtual meetings on from the first coronavirus death in Europe, expectations are low.

Finance ministers have lined up a 540 billion-euro package, unprecedented in itself, to address the continent’s immediate needs. Progress on the longer-term rebuilding program is likely to be incremental at best.

Officials with knowledge of the preparations said that while agreement is growing around the perimeter of a economic recovery plan, squabbling over the details will probably be the dominant feature. And they won’t set deadlines.

That doesn’t mean that, slowly but surely, a compromise isn’t emerging. It always does.

“Everyone is aware that the future of the EU is at stake in how we respond to this extraordinary crisis,” French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said at a briefing in Paris on Tuesday. “All we’ve done to support our economies will be useless if we aren’t able to decide on a massive, immediate and simple stimulus.”

Europe is entering what is projected to be the steepest recession in living memory and the timing of the recovery will depend on factors largely outside the control of policy makers, such as the availability of a vaccine or a cure for the disease.

The fallout from the pandemic is once more tearing at the fabric that holds the disparate group of nations together. That was the case in the Greek crisis a decade ago, with the 2015 influx of more than a million refugees and most recently with Brexit.

In short, the EU’s been caught in the jaws of a permanent existential crisis for years and the process of staving off such threats can seem bewilderingly slow.

As the death toll increases, ideas about how to take on such an unprecedented menace have already been batted back and forth between leaders, their finance chiefs, envoys in Brussels and the bloc’s often lampooned bureaucracy.

At the heart of the discord over financing the recovery lie diverging views over how the EU should really work. Hard-hit southern countries like Italy and Spain are demanding joint debt issuance -- to spread the financial strain across the whole bloc -- but a group of governments led by Germany and the Netherlands has rejected this over fear that they’d be stuck with the bill.

Sticking Plasters

In an effort to bridge the gap, France proposed a temporary fund financed by joint issuance, but operated for only a few years to kick-start the economy. That’s the structure that leaders are converging on, but it’s still not clear whether it will achieve what France (and many other countries) are hoping for.

The Germans and the Dutch want to offer low-interest loans which would still leave highly indebted countries saddled with even more liabilities. French officials said this week that however the fund is structured, it has to offer handouts not loans. There is also still debate on the size of the fund, how it will be financed and what the money will be spent on.

With the issue of joint debt unresolved, focus has shifted to another program: the EU’s seven-year budget that’s set to kick in in January. That’s the only significant option in the EU toolkit for making direct transfers of public money from one country to another.

For that reason, talks on the longterm budget are notoriously acrimonious and it’s all the more complex this time round as the U.K.’s departure from the EU that has left a hole in its finances.

“The instrument we can do it with is the EU budget. It must be possible to do things quickly in a crisis situation and then of course conduct a refinancing in the years after,” German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz said in an interview with ZDF television Thursday. “That’s the best way to do it and it’s in line with European treaties, which is also very important.”

While leaders have not yet received any specific proposals, the commission is floating a plan to mobilize about 2 trillion euros using both the next seven-year budget and a new financing mechanism. The compromise proposal was set out in an internal commission document seen by Bloomberg News.

Any solution must “be dedicated to deal with this unprecedented crisis” EU Council President Charles Michel, who will chair the discussion, said in a letter to leaders. “It should be of sufficient magnitude, targeted toward the sectors and geographical parts of Europe most affected.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.