Japan Shows Why Italy’s Yields Are a Form of Euro Membership Fee

Europe’s fiscal fragmentation may be inflicting an extra fee for euro membership onto indebted southern countries.

(Bloomberg) -- Europe’s fiscal fragmentation may be inflicting an extra fee for euro membership onto indebted southern countries, underscoring the case for the region’s new recovery fund.

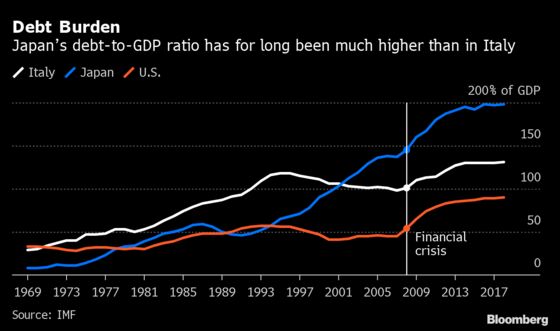

A perspective to identify that cost could be to compare Italy with Japan. Both those countries contend with aging societies and a struggle to generate inflation and growth. Both have vast debts, with Japan’s considerably bigger. Somehow though, its borrowing costs are significantly lower and more stable.

One reason, according to Pacific Investment Management Co. and Mizuho International Plc, is that Japan has its own central bank, which can hone action for its specific economy and also work to keep the country’s fiscal costs in check. By contrast, Italy experiences the European Central Bank’s monetary policy for the whole region.

“Italy is also a sovereign state, but it shares the euro with 18 other countries, and cannot purely by itself set the legislation that governs what the ECB does,” said Andrew Bosomworth, a managing director at Pimco. “It shares similarities with local governments and other borrowers that borrow in foreign currency.”

That sobering thought will no doubt haunt ECB officials this week as they discuss more stimulus for the coronavirus-stricken region, and review efforts to prevent spreads of members’ bond yields from widening.

Such analysis doesn’t mean Italy would be better off leaving the euro. Greece’s debt crisis, which brought it within a whisker of exiting, showed the costs are prohibitive.

It’s also hard to argue that Italy, with its 20th century currency crises and inflation, could have been treated by investors as being as creditworthy as the haven of Japan if it hadn’t joined. The latter is also, comparatively, an economic powerhouse.

But if Italy and its ilk really do face additional membership dues for being in the euro -- at a time when their economies are already diverging from the richer north -- that could add to the case both for more urgency in ECB efforts, and for deeper fiscal integration, currently in the form of the European Union’s Recovery Fund.

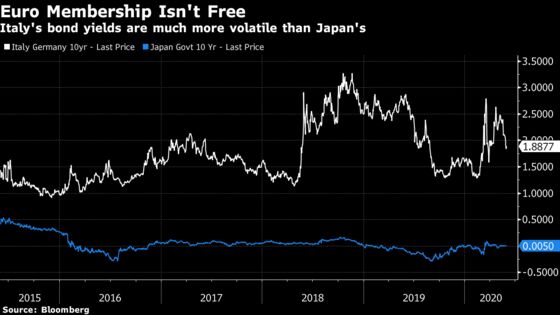

While many of Europe’s core bond markets reflect “Japanification,” a world of tepid inflation and almost non-existent volatility, Italy’s is an exception.

Its benchmark 10-year bonds yield around 1.5%, around two percentage points more than those on similar-dated German securities -- a spread that has ranged from less than 100 basis points to well over 300 basis points over the past five years. In that time, Japan’s bonds tended to trade in a narrow 40-basis point range around 0%.

The difference is “100% to do with Italy’s economy and debt metrics being weaker than the euro-area average,” said Peter Chatwell, head of European rates strategy at Mizuho. “The ECB doesn’t set monetary policy for Italy, it sets monetary policy for the euro area.”

While Italy has failed to pursue growth-friendly policies, joining the euro also means it can no longer devalue its currency to stay competitive. But it has benefited from the stability of membership, and has enjoyed years of stimulus other countries needed less.

Even so, Japan shows how much closer fiscal and monetary policies can be -- unlike in the euro region, where EU rules keep finance ministries at arm’s length from the ECB.

Such coordination was further cemented last month in a joint statement by Finance Minister Taro Aso and Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, declaring they “will work together to bring the Japanese economy back again on the post-pandemic solid growth track.”

That joined-up focus on a single country and currency ultimately gives Japan and other economies greater flexibility to manage strained public finances.

‘Really Extreme’

“Central banks were created to avoid government default -- it’s what they have been designed to do and they can serve this function in countries like Japan and the United States,” said Gilles Moec, chief economist at AXA in London. “In the euro zone, we have an explicit prohibition of monetary financing. You can’t do it. It’s really extreme.”

Another comparison is with U.S. states, whose borrowing costs move in a more synchronized way than euro members, benefiting in part from greater fiscal flexibility and more perceived backing from the Federal Reserve than Italy enjoys from the ECB, according to Bloomberg Intelligence Senior U.S. Municipals Strategist Eric Kazatsky.

That volatility is a justification for the ECB’s emergency bond buying to cap spreads between countries, created after President Christine Lagarde mistakenly gave investors the impression that officials lacked resolve in supporting Italy’s membership.

What made that episode all the more unsettling was the country’s pre-euro experience of market instability, such as when the lira was ejected from the region’s Exchange Rate Mechanism, along with the pound in 1992.

Italians haven’t forgotten that speculative attack, and are wary of going it alone. Europe has also offered a useful external constraint to leaders trying put the country’s books in order and resist spending pressure from myriad interest groups. On its own and prey to market forces, Italy could also face greater political instability.

But the idea that the euro might be less of an economic comfort blanket than a straitjacket suggests a pressing need for European fiscal integration. The EU’s push for that features a 750 billion-euro ($832 billion) facility with jointly issued debt.

“The recovery fund is the breakthrough that the euro area needs,” said Mizuho’s Chatwell. “Having a common platform for issuance -- don’t say it too loudly, but that is what the fund is -- will reduce such imbalances.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.