EU Is Out to Prove Saving the Planet Doesn’t Have to Hurt Growth

EU Is Out to Prove Saving the Planet Doesn’t Have to Hurt Growth

(Bloomberg) -- The European Union’s push to banish carbon from its economy is offering the world a real-time experiment on whether such a shift is achievable without hurting short-term prosperity.

With the COP-26 conference concluding this weekend with some thwarted ambitions toward international action on curbing emissions, the bloc is forging ahead with a strategy cementing its role as the foremost global pioneer in turning green rhetoric into reality.

Those efforts will demonstrate just how much of an immediate economic trade-off is required, providing a crucial roadmap for global counterparts.

Brussels officials assert any damage from their plan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 will be relatively minor, a claim underscored by branding the project as a “growth strategy.”

For such a scenario to play out, policies and technologies need to evolve enough to allow expansion while eliminating greenhouse gas emissions, defying the experience of history where prosperity and pollution went hand-in-hand. Ottmar Edenhofer, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, says that’s not too ambitious.

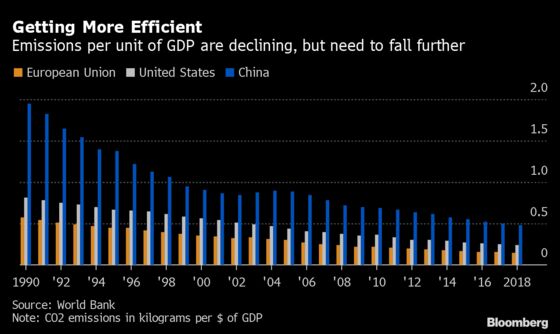

“There’s no reason to think that a law of nature will make it impossible to decouple an economic quantity like gross domestic product from a physical one like emissions,” he said. “The European Union is the only region in the world where emissions have started to decline. It’s not going fast enough to reach net zero emissions in 2050, but we’ve started, and it’s a realistic perspective that the decoupling will succeed.”

The EU wants to become the “the world’s first climate-neutral continent” by 2050. The bloc is trying to cut emissions by at least 55% by 2030, and to do that, it is eyeing measures including an expansion of what is already the largest carbon market globally, and a levy on imports from nations with lower environmental standards.

Other initiatives focus on specific industries, like a ban on new combustion-engine cars by 2035. The EU is also devoting more than a third of its 800 billion-euro ($928 billion) Covid recovery plan to combat climate change.

Getting the economics of the transition right is all the more important after the pandemic shriveled regional output last year and sent government debt soaring, providing yet another setback after the debt crisis of the past decade almost shattered the euro.

The European Commission, in its official calculation, says the impact of its green drive on the economy could range from a hit of 0.7% to a boost of 0.55%. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions “if done efficiently is not a risk to the EU economy,” it said last year.

Others aren’t so sangine. Jean Pisani-Ferry of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington has warned such long-term predictions may conceal disruption along the way, including a negative hit to economic output.

How to balance climate transition with the need to support livelihoods and foster voters’ consensus for such change is a fraught challenge. Extreme advocates claim the circle can’t be squared without less economic activity, for example by cutting back on consumption or reducing working hours.

But a recent paper by the Bruegel think tank in Brussels argued that “hoping for humanity to sacrifice growth appears unrealistic,” meaning large parts of the world couldn’t develop further, or only at the expense of richer nations shutting down even more drastically. That makes the EU’s pathfinding all the more important.

No Choice

“Economic growth still means welfare state, having the resources to pay pensions to your citizens, providing them with education and all the services we want,” said Simone Tagliapietra, a senior fellow at Bruegel and one of the authors of the paper. “Green growth is not really a choice, but an imperative.”

Away from Brussels, other analysts reckon such a goal is within the EU’s reach. Credit Suisse Group AG economists Franziska Fischer and Neville Hill said last month that higher carbon prices and tougher regulations sought by the EU could be offset by the investment needed -- so “the net impact is likely to be small.”

The International Monetary Fund last year estimated that a policy package combining an initial spending push with steadily rising carbon prices “would deliver the needed emission reductions at reasonable output effects.”

There is even stronger consensus that no action at all could leave a disastrous impact on economic growth -- even without considering existential questions on the planet’s health.

Mitigating climate change will boost global output by 13% by the end of the century, according to the IMF. The BlackRock Investment Institute said in a report earlier this year that without action, global GDP will already decline over the next 20 years.

“The commonly held notion that tackling climate change has to come at a net cost to the global economy is wrong,” said authors including former Swiss National Bank President Philipp Hildebrand.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.