Confused Danes Turn on Economists Over Negative Rates

Economists Fall Out of Favor in a Negative-Rate Test Case

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up here to receive the Davos Diary, a special daily newsletter that will run from Jan. 20-24.

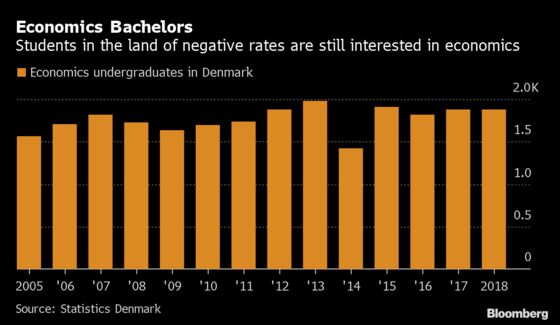

In the country that’s had negative interest rates longer than anywhere else, economists are going through a bit of a rough patch.

Since Denmark introduced subzero rates in mid-2012, citizens have struggled to get their heads around a world in which savers are punished, borrowers are rewarded and the basic laws of risk-return feel like ancient mythology.

“People just don’t understand negative rates,” said Jes Roerholt Asmussen, the chief economist at Handelsbanken in Copenhagen.

Trying to explain the incomprehensible -- and make predictions that people take seriously -- is proving increasingly difficult, according to Asmussen. And that’s one reason why his profession is now regarded with increasing skepticism, he says.

It’s the latest sign that, since the global financial crisis of 2008, experts are struggling to reassert their credibility. Helge Pedersen, chief economist at Nordea in Copenhagen, says part of the reason his industry has suffered reputational damage is due to its failure to predict negative rates in the first place. (Nordea now expects Denmark’s central bank to keep its main rate at minus 0.75% until the end of 2021.)

Asmussen says he already noticed a shift in sentiment toward his profession a little over decade ago. “Suddenly I was receiving angry calls for my role as a harbinger of bad news.”

The Economy

Serious questions have also been raised in Denmark around the basic reliability of the information on which economists base their calculations. The Danish statistics office was recently caught in a data debacle after it drastically adjusted years of GDP numbers, revealing the economy was bigger than people thought.

Las Olsen, chief economist at Danske Bank, says there’s now “less interest” in what economists do. He points to an example at the Danish Tax Ministry, where its number crunchers were ridiculed for asserting that adding 19 kroner ($3) to the price of a pack of cigarettes would create 900 new jobs (the calculation contained some dodgy assumptions on human nature).

The picture people are left with is that “economists don’t know what they’re talking about,” Asmussen said.

But the problem goes well beyond the experiences in Denmark. Asmussen points to the increasingly impossible task of forecasting accurately in a world dominated by tweets from U.S. President Donald Trump.

There’s “a lot of noise in the information cloud,” he said. “I can’t model Trump.” That means that “economists are now operating on less certain ground because we have no models to work on.”

“Predicting the future is like driving a car blindfolded while getting directions from a back-seat passenger who’s looking out of the back window,” he said.

But Pedersen at Nordea suggests the issue is probably cyclical.

“Economists are always more in demand when the economy is doing badly,” he said.

--With assistance from Morten Buttler.

To contact the reporter on this story: Nick Rigillo in Copenhagen at nrigillo@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tasneem Hanfi Brögger at tbrogger@bloomberg.net;Christian Wienberg at cwienberg@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.