Disabled Workers, Already in a Tough Spot, Now Have It Worse

Disabled Workers, Already in a Tough Spot, Now Have It Worse

(Bloomberg) --

The global pandemic is worsening a labor market that already presents obstacles for workers with disabilities.

For America’s almost 30 million working-age disabled citizens -- who deal with challenges including seeing and hearing, as well as getting around -- the large majority of job opportunities lie in food service, hospitality and retail. But when virus lockdowns brought those sectors to a standstill, workers with disabilities quickly saw their jobs vanish.

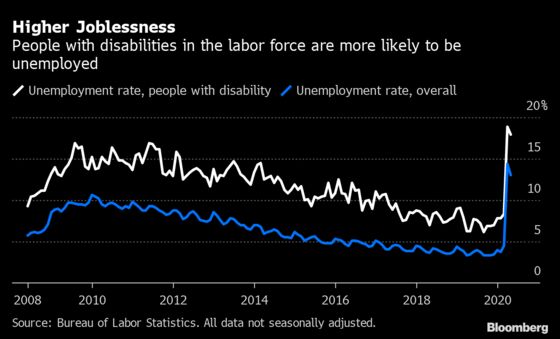

During the peak of pandemic-induced job losses, 18.9% of disabled Americans were unemployed, compared with 14.3% of the non-disabled population, according to unadjusted April data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In June, as states started to reopen their economies, the jobless rate for disabled Americans fell to 16.5%, while the rate for everyone else dropped to 11% -- signaling a faster recovery for the general population than for those with disabilities.

“With the recovery, we’re seeing some businesses and industries take people back first that can work full-time and can do a broader array of tasks,” said Thomas Golden, executive director of the Yang-Tan Institute on Employment and Disability at Cornell University. “That further marginalizes the population of people with disabilities who were working part-time or doing specific tasks that they could do.”

‘Very, Very Hard’

Having a disability can mean different things. The U.S. Census Bureau breaks disability into six categories: visual, hearing, ambulatory, cognitive, self-care and independent living.

Of Americans with disabilities that were employed in 2018, the largest share had a hearing disability, at 53.6%, followed by visual disabilities at 45.4% and ambulatory disabilities at 25.6%, according to a Cornell analysis of the bureau’s American Community Survey. The numbers add up to more than 100% because many people have multiple disabilities.

Sherry Bell was working as a janitor at Valley Children’s Ice Center, an ice rink in Bakersfield, California, when she was furloughed in March. Bell, who has an intellectual disability that affects the speed at which she learns new tasks, says communication in the workplace has been a challenge in the past, with some of her bosses not properly explaining what was expected of her, and others speaking to her disrespectfully.

Bell is now receiving unemployment benefits and is working with PathPoint, a nonprofit for Californians with developmental disabilities that she has been involved with for five years. She’s trying to find a job to supplement her income in the interim. But finding work environments that accommodate her disability isn’t always easy.

“It was very, very, very hard,” Bell, 37, said of accommodating her disability at former jobs. “Some bosses were nice, some bosses were not.”

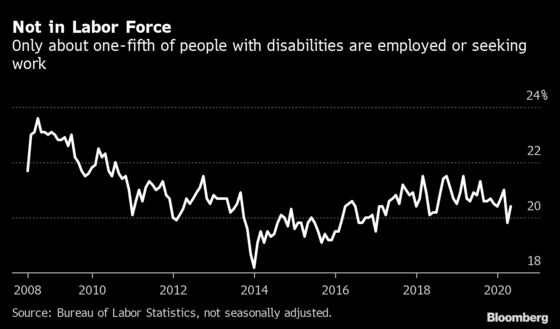

The disabled population faces barriers to entry when it comes to finding work because not all employers provide necessary accommodations, Golden said. For that reason, only one-fifth of disabled Americans over 16 are included the labor force to begin with, according to labor-force participation-rate data from the BLS.

With coronavirus prevention efforts rapidly changing business operations, even employees who do return to the workplace are met with new constraints such as different office layouts.

The federal stimulus package didn’t include funding for vocational rehabilitation or home and community-based services under Medicaid, meaning that disabled Americans aren’t getting additional workplace support, said Julie Christensen, director of policy and advocacy at the Association of People Supporting Employment First, a nonprofit that advocates for workplace inclusion.

“For many people with disabilities, their ability to be successful in the labor market is having access to services and support that can help them acclimate to the job,” Christensen said. “Business processes are changing -- new equipment, plexiglass -- how do you adjust to all of these things when the system there isn’t getting funded?”

While a large portion of disabled workers have been let go from jobs at retail stores and in restaurants, others have voluntarily chosen to leave because of pre-existing conditions that make them vulnerable to disease, said Philip Kahn-Pauli, policy and practices director at RespectAbility, a nonprofit that advances opportunities for people with disabilities.

Many disabled Americans rely on public transportation to commute, so they’ve stopped working to limit exposure and avoid bringing the virus home, especially since a large portion of the population lives in group homes or with roommates.

“There’s reasonable fear -- a majority of deaths are people with a pre-existing condition,” Kahn-Pauli said. “So if you’re a person with a disability, are you going to accept unemployment if it means you’re not going to risk dying?”

Some disabled workers who have lost their jobs and can’t immediately find a new one will wind up applying for Social Security Disability Insurance, a program that provides income supplements to people who are physically restricted in their ability to work. The trouble is, it can take as long as three years to become entitled to benefits, said Golden, the Cornell University researcher.

Since millions of Americans aren’t working as a result of the pandemic, they’re not paying Social Security taxes, which means income for the fund isn’t growing, Golden said. That could have a longer-term impact on the fund’s solvency and threaten benefits in the future. The Social Security Administration paid out a record $145 billion in disability-related benefits last year.

The population is “very vulnerable during the application process,” Golden said. And while benefits provide an “income safety net, they foster a greater reliance on the system rather than developing innovative return-to-work programs.”

One bright spot for workers with disabilities could be the widespread acceptance of at-home work, Pauli said. While many Americans with disabilities have trouble getting to an office, they can more easily work on a computer from home, which opens up avenues that didn’t exist before. Despite that benefit, Pauli says he’s worried about the population’s economic security as the recession continues.

“If this crisis continues in the long term, we could see a lot of depths of despair before people start going on benefits,” Pauli said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.