Dirty-Money Ties Worried Some at Swedbank While Bosses Kept Mum

Dirty-Money Ties Worried Some at Swedbank While Bosses Kept Mum

(Bloomberg) -- In the summer of 2018, a senior anti money-laundering official at Swedbank AB appeared anxious as he read reports that its competitor Danske Bank A/S could be fined by U.S. authorities for alleged crimes in the Baltics.

“I’m afraid that if they are sentenced, we will be in focus,” he wrote in an email to then-Chief Compliance Officer Cecilia Hernqvist. She replied: “Fingers crossed.”

Danske, which has since admitted handling suspicious funds in one of Europe’s largest-ever money laundering scandals, is still awaiting judgement by regulators in the U.S. But Swedbank executives were right to be concerned. In the months that followed, Swedbank was also sucked into the maelstrom of the Nordic-wide revelations of dirty money flows from the former Soviet Union.

The lender has been fined in Sweden and remains under investigation by U.S. authorities.

Email exchanges, reports and witness testimonies released this week by Sweden’s Economic Crime Authority that run to almost 4,000 pages add to evidence that some Swedbank managers were aware of significant links to the potential laundering, including through Danske. Yet when pressed by outsiders, former Chief Executive Birgitte Bonnesen appeared to be less than forthcoming about those connections.

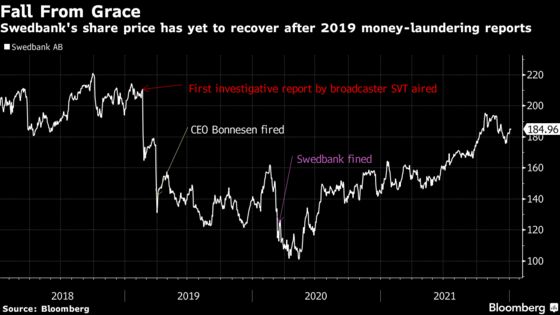

The documents (written mostly in Swedish) were made public as part of the indictment against Bonnesen for serious fraud. The ex-CEO is also accused of disclosing insider information when on Feb. 18, 2019, she gave the bank’s biggest investors advance notice of an investigative program aired by the public broadcaster two days later. Those revelations sent the lender’s stock tanking, losses the shares have yet to recover.

Bonnesen, who was ousted in March 2019 after steering the bank for three years, denies the charges.

“There is no doubt that Birgitte Bonnesen was made a scapegoat,” her lawyers Per Samuelson and Christina Bergenstein, with legal firm SSW, said in the filing. They described her statements as “completely normal elements of her work as CEO,” adding “it was simply her duty to comment.”

Indictment against Bonnesen should benefit Swedbank, which “has been clear about having made mistakes” in the past, according to Joakim Bornold, an adviser at Soderberg & Partners.

“It’s good that the focus is shifted away from the bank toward an individual employee,” he said by phone. “You might think that it’s bad publicity, but it’s directed at Bonnesen in a way that suits Swedbank very well.”

Bonnesen had received reports drafted by the bank’s compliance officers on exposure to Danske -- described by its author in an email as “not looking good” -- in July of 2018 and a final report in September of that year, according to the investigation report released this week. But in the months that followed, she told Swedish media the bank “found nothing” when investigating transactions with Danske.

She also stressed in other interviews, statements and at quarterly earnings calls with analysts that Swedbank’s business model was entirely different from Danske’s and not focused on non-resident clients of the Baltics, which included those often implicated in laundering.

Swedish authorities in 2020 fined Swedbank a record 4 billion kronor ($440 million) for breaching money-laundering rules. Swedish newspaper Dagens Industri reported in December 2020 that federal authorities in the U.S., including the Justice Department, the FBI and a federal prosecutor’s office in New York are probing Nordic banks including Swedbank.

Unni Jerndal, a spokeswoman for the Stockholm-based lender, declined to comment on the released documents, saying those “concern historical information in a legal process that does not involve the bank,” and wouldn’t specify the status of any ongoing probes.

Often regarded a model of successful transition from communism, the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were swift to reduce economic dependence on their former Soviet overlord after regaining independence in 1991. Yet the region remained a window for capital flight from Russia to the West long after the Nordic lenders came to dominate its financial sector.

Banks transfered money from east to west, often in dollars, and often with murky origins in what was a widely-touted business model. That began to change in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea -- triggering U.S. sanctions and closer scrutiny of financial flows. More scandals - such as the “Russian Laundromat” - emerged and lenders were shut. The U.S. Treasury proposed banning ABLV from the American financial system, designating it as a primary money-laundering concern in February 2018, sparking its demise. ABLV denied the accusations.

When Danske revealed in September 2018, that “a large part” of the 200 billion euros ($227 billion) in flows handled by the bank between 2007 and 2015 were suspect, the news triggered a surge in international scrutiny that also engulfed Deutsche Bank AG, the main correspondent bank for Danske’s Estonian unit.

The newly revealed Swedbank documents seemingly point to repeated instances in which Swedbank’s management tried to play down its potential role in money laundering.

Swedbank had been aware of shortcomings at its Baltic operations already in 2016, when an internal compliance report by Hernqvist’s predecessor pointed to problems in risk assessment, know-your-client processes as well as screening and transaction monitoring. The department’s attention turned to the region in 2015, and its investigation found “rather serious shortcomings,” including transaction monitoring that was done by simply going through Excel spreadsheets, Hernqvist’s predecessor told the police in September 2019.

In 2017, an investigation for the bank by law firm Erling Grimstad showed a “high risk of widespread money laundering” and “significant risk of Swedbank involvement in other criminal activity as the bank has no control of money flow in and out of accounts,” triggering a purge of high-risk clients that year.

Another report commissioned from Grimstad at the end of 2018 said it found “several similar risks in Swedbank Estonia” as those identified at Danske’s local unit, adding there were “major breaches” of core anti money-laundering obligations at Swedbank Estonia.

“Oh f*ck, this is not sparing on Estonia,” a senior Swedbank compliance officer said in an email to a colleague on Dec. 13, 2018. “Point of no return...nasty times ahead.”

Over the years, Swedbank had also attracted the suspicion of U.S. authorities.

In 2016, the New York Department of Financial Services had asked Swedbank’s U.S. operation for details about its exposure to clients of Mossack Fonseca & Co., the law firm whose leaked files put a spotlight on offshore finance in what became known as the Panama papers.

Another letter from DFS in 2018 requested details on exposure for “the global operations of Swedbank” to the law firm, the indictment documents released this week show. Hernqvist, the chief compliance officer at the time, excluded the lender’s Baltic subsidiaries from the bank’s response, according to an email dated Feb. 23, 2018. A month later, a senior officer wrote “Just so you know, we do have a lot of hits on MF in the Baltics.” Hernqvist replied, “That’s why I wanted to get them out of the scope :)”.

Hernqvist, who has not been accused of any wrongdoing, declined to comment when reached by Bloomberg News via LinkedIn.

Hernqvist also said in an email to Bonnesen dated Sept. 23, 2018, that the bank hadn’t done much to prevent money laundering in the past and “I’m afraid there may be a lot of old/historic stuff so I think we should be a bit careful.”

The bank’s senior management “failed to establish” clear lines of responsibility for preventing dubious flows, was the conclusion of an audit by law firm Clifford Chance published in March 2020, commissioned by Swedbank. It found that between 2007 and 2019 client transactions totaling $40 billion mainly at Swedbank’s Estonian unit represented a “high risk” of money laundering.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.