Deutsche Bank CEO’s Last-Ditch Plan to Save Best of His Business

Deutsche Bank's Last-Ditch Plan to Save the Best of Its Business

(Bloomberg Markets) -- Christian Sewing’s shock was plain to see, the color draining from his face. The chief executive officer of Deutsche Bank AG had just unveiled his long-awaited plan to fix the troubled lender. It included a retreat from equities trading, a focus on corporate banking, and the elimination of 18,000 jobs, a fifth of the workforce. To underscore his conviction, he’d even pledged to invest a chunk of his own pay in Deutsche Bank stock every month.

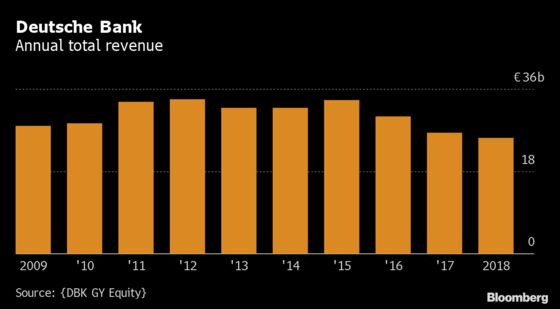

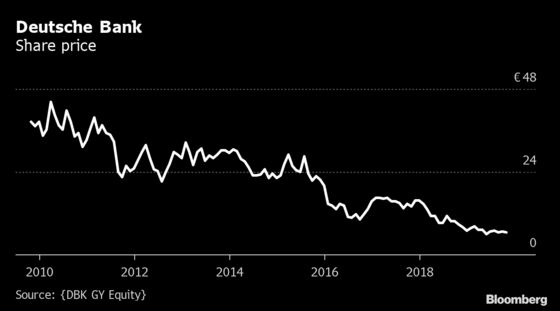

Then he checked his phone. The shares were in free-fall; they lost as much as 7.3% that day, July 8, and tumbled again on July 9. Shareholders had reached the same, grim verdict: Sewing’s goals were unrealistic for a bank that had consistently disappointed investors. His plan continued to rely on a global investment bank with shrinking revenue and a low-profit retail bank in a home market plagued by fierce competition and negative interest rates.

It was a sucker punch for the former risk manager. Sewing had spent his entire first year as CEO building up to this moment. He’d purged the management board of dissenters, wooed regulators and investors. He’d rejected an alternative strategy that some key stakeholders favored: merging with Deutsche Bank’s German rival, Commerzbank AG. But the market reaction was a reminder that if his strategy was going to work, it wouldn’t happen quickly, and there was no room for error.

History contains innumerable examples of corporate giants struggling to adapt to a changing world. What makes Deutsche Bank’s story particularly resonant is not just that the risks involve a systemically important bank with a €1.5 trillion ($1.66 trillion) balance sheet. It’s also the way the bank’s fate follows the trajectory of corporate globalization over the last three decades.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the bank expanded rapidly overseas and took greater risks, at one point becoming the world’s largest lender and a top trading firm. Then, in the wake of the 2008 credit crisis, both its business model and its reputation came under attack.

Even the proposed solution—Sewing, the first German citizen to serve as sole CEO in 16 years, with his plan to shrink the bank closer to its domestic roots—echoes the inward-looking political prescriptions that have gained prominence around the world. So now Deutsche Bank’s global shareholders, including entities in Qatar and the U.S., are left to wonder how such a strategy can succeed in the 21st century.

The two wretched days in July were followed by more pain. Piecemeal cuts to the business by Sewing’s predecessors had triggered a protracted fall in revenue without restoring profitability. Sewing pledged in the July announcement that revenue from businesses the bank is keeping, would grow 2% annually, to about €25 billion by 2022. But within weeks he had to acknowledge that lower interest rates made that goal more difficult. In September the bank softened the 2022 target to €24 billion to €25 billion. In October, when Deutsche Bank reported yet another quarter of declining revenue, the stock plunged again.

Each sell-off deepens the hole in which Sewing finds himself. The share price, now down about 90% from its peak in 2007, has fallen about 40% since he took over in April 2018. That ruled out any chance of asking shareholders for more money, leaving the CEO to draw down the bank’s capital cushion to fund the new plan. With less and less room to maneuver, Sewing, 49, is axing the entire equities trading arm.

The more powerful trading business at Deutsche Bank has always been fixed income. In the years before the financial crisis, that unit expanded massively to become an industry leader and one of the company’s biggest sources of revenue. But stricter postcrisis regulations, higher capital requirements, and negative interest rates have all made it harder to make money. Sewing has been cutting jobs in the areas that trade interest rate-related securities. The bank has vowed to turn around the shrinking unit, but the October results—in which fixed income led the revenue decline—once again underscored the challenge.

Sewing’s surgery is all part of a last-ditch effort to salvage the limbs that are still functioning. Should he fail, Deutsche Bank, which celebrates its 150th anniversary in March, will have few options: sell more businesses, be acquired, or—given its crucial role in keeping Germany’s export economy humming—face the prospect of being nationalized.

A former top executive at the bank who knows the CEO well frames the predicament this way: Sewing is the bank’s “last option.” There’s no alternative. If he can’t fix it, Deutsche Bank will fall apart.

Paul Achleitner, the chairman who’s presided over failed turnaround efforts by Sewing’s predecessors since 2012, sees it differently: “Deutsche Bank has gone through quite a few crises during its 150 years of history, but it was always able to find exceptional executives to lead it out of those,” he says. “And I’m convinced Christian Sewing will be one of these critical leaders.”

In early 2018, with then-CEO John Cryan on his way out, Achleitner asked Sewing what he would do differently. One of two deputy CEOs at the time, Sewing used his ski vacation in Lech, Austria, to write a 40-page paper outlining much of what would eventually end up in his strategy announcement. He drew heavily on his history in the corporate bank, the division that provides profitable basic financial plumbing services such as cash management, trade finance, and payment services. His wife drove the 475 miles back home to Osnabrück so he could keep scribbling in the passenger seat.

He still lives in the rural northwest of Germany where he grew up. On weekends he can occasionally be seen having a beer at a local Greek restaurant. Unlike four of his five most recent predecessors, Sewing lacks experience in investment banking. He hasn’t worked at a big consulting firm or graduated from a prestigious college. He finished high school with a middling grade (a 2.4 average, equivalent to a B-) and did an apprenticeship at Deutsche Bank before getting a diploma from the Bankakademie Bielefeld and Hamburg.

His strengths lie elsewhere. “He knows how to cope with setbacks, which probably helps him in his current role,” says Wolfgang Kirsch, the former CEO of DZ Bank AG, the parent company of DZ Hyp AG, a mortgage lender where Sewing was a management board member from 2005 to 2007, his only stint outside Deutsche Bank.

Sewing is levelheaded and straight-talking. People who’ve worked with him unanimously praise his ability to execute a plan once it’s decided. He’s less comfortable, some say, with big strategic decisions. He was always one of the quieter management board members and is less skilled at presenting a sweeping vision for the bank than his predecessors, they say. One former colleague says Sewing had an instinct for what was important and achievable. Another says he’s relentless in following up on targets but will hesitate to make conceptual decisions until he feels he has enough details.

These people—and more than a dozen other former and current colleagues interviewed for this story—asked for anonymity to discuss their views in private. Sewing declined requests for an interview or comment.

For Deutsche Bank, a focus on execution may not be a bad thing. By the time Sewing took charge, years of expansion and takeovers had left the bank with multiple fiefdoms and competing centers of power. Management board members blamed one another for the troubles instead of working as a team, according to people familiar with the matter. Sewing responded to the infighting, which he has called “Deutsche Bank’s disease,” by replacing top managers with executives he trusted, almost all of them German.

First, Kim Hammonds, the operating chief who called the bank “the most dysfunctional’’ company she’d ever worked for, was replaced with Frank Kuhnke, a Deutsche Bank lifer Sewing knew from when they’d worked together in Japan. Nicolas Moreau, the Frenchman leading the bank’s DWS asset management unit, was replaced by Asoka Wöhrmann, who hails from the same region as Sewing. In the July restructuring, Sewing ousted three more executives and took control of the investment bank from Garth Ritchie, shifting the center of power firmly back to Frankfurt from London.

After the disappointing third-quarter results in October, Sewing promoted Fabrizio Campelli, a former head of strategy who most recently led the bank’s wealth management division, to a newly created role as head of transformation. He also recruited Michael Ilgner, a former Olympic water polo player who was leading the German Sport Aid Foundation, to helm human resources.

In 2018, while he cemented his control over the company, Sewing was still grappling with the plan to focus Deutsche Bank on corporate banking that he’d formulated on the ski trip. As a first step, he’d announced a 25% reduction in headcount at the equities business shortly after taking over and was now waiting to see if that was enough.

By late December, it became clear that it wasn’t—and Sewing roped in one of his closest advisers, Alexander von zur Mühlen. They’d worked together under Hugo Bänziger, the chief risk officer at the time and one of Sewing’s most important mentors. “The two had a great connection,” recalls Bänziger, who left Deutsche Bank in 2012. “They were my key employees.”

Von zur Mühlen’s investment banking background—he’d served as co-head of global capital markets—helped Sewing build on the paper he’d drawn up during his ski vacation. They looped in more executives, including investment banking chief financial officer Christiana Riley, who now runs the bank’s U.S. operations, to flesh out what became internally known as “Project Cairo.” It was soon clear that much, much more of the trading business needed to go.

It was a difficult decision, though less so for Sewing than for Achleitner. As a young dealmaker at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in Germany, Achleitner had advised Deutsche Bank on its 1998 purchase of Bankers Trust, turning the German lender into a trading giant and, briefly, into the world’s largest bank.

Achleitner remained a defender of a strong securities business when he became Deutsche Bank’s chairman 14 years later, but the world had changed. The industry’s years of global expansion and aggressive risk-taking had resulted in the 2008 financial crisis, spurring tougher financial rules and a populist backlash against globalization.

For banks, regulators made trading a lot more expensive, and authorities caught up with large-scale misconduct—from the sale of toxic mortgage bonds to market manipulations and money laundering. Deutsche Bank alone paid more than $18 billion in fines in the decade following the crisis. Efforts by central banks to stimulate economic growth, especially in Europe, resulted in negative interest rates that have eroded income from lending.

In an effort to preserve the core of Deutsche Bank’s investment bank, Achleitner in early 2019 encouraged merger talks with Commerzbank, a struggling German rival. He saw Commerzbank’s large deposit base as a way to help cut funding costs for the securities unit. Germany’s finance ministry and Cerberus Capital Management LP, a top shareholder in both banks, were also in favor.

Sewing was skeptical of a merger that would expand the bank’s presence in the overcompetitive German market. But with three key stakeholders breathing down his neck, he put aside Project Cairo and started crunching the numbers. The talks were formally announced on March 17. Commerzbank CEO Martin Zielke pushed for a quick decision because employees were unhappy and opposition started to form, but Sewing sought more time to figure out the cost savings a transaction would bring.

Meanwhile, Sewing was quietly exploring a much bolder option, one that would have upended the banking world. Deutsche Bank and Switzerland’s UBS Group AG held preliminary discussions about a megamerger that would have created continental Europe’s biggest financial institution. The talks, codenamed “Project Santiago,” grew out of stalled negotiations to combine the banks’ asset management businesses. But they, too, fizzled.

The Commerzbank talks were extended, sending employees to work on due diligence over the Easter holidays, but the potential cost savings just didn’t add up. In his days as a risk manager, Sewing had learned how to put a brake on deals being pushed by hard-charging investment bankers. With Project Cairo in the wings, and the benefits of a Commerzbank deal uncertain, he walked away, despite the support for the deal from Cerberus, the finance ministry, and his own chairman.

It was a bold move for a CEO just a year into the job, say people close to the decision. But shareholder support for Achleitner had begun to wane after years of unsuccessful turnaround efforts. At the annual general meeting, he bore the brunt of shareholders’ frustration, with one asking why the chairman kept his job when even the leader of the Catholic church, German Pope Benedict XVI, had stepped down from his lifetime role.

Deutsche Bank’s biggest shareholders went even further, directly approaching candidates to gauge their interest in replacing Achleitner. Some representatives of the Qatari royal family, which owns a combined stake of more than 6%, held talks with an international recruiting firm and reviewed potential executives, people familiar with the matter say. They’re debating whether to try to force the chairman out before his term expires in 2022.

That gives Sewing an important advantage over his predecessors. One former executive describes the dynamic this way: Achleitner needs Sewing, but Sewing doesn’t need Achleitner, and they both know it. For his part, Sewing has said he’s glad to have Achleitner as chairman.

The end of the Commerzbank talks on April 25 set off a flurry of planning as Sewing decided how much surgery would be needed to restore Deutsche Bank to profitability. After five years of negative interest rates in Europe, Chief Financial Officer James von Moltke and his team were working on the assumption that rates would eventually rise.

But the trade war between the U.S. and China weighed heavily on Europe’s export economy, and expectations for higher rates reversed. By the time the bank announced new targets, the underlying assumptions were out of date. At least one major shareholder, according to people familiar with the matter, had warned the bank before Sewing’s July announcement that it shouldn’t use inflated targets, especially given its history of overpromising and underdelivering. In September, to account for the increased headwinds from the economy and interest rates, the bank softened its revenue target. Regulators generally support the CEO’s plan, but a few of his decisions have raised eyebrows. Some regulators approached him to express concern that running the investment bank is too big to be treated as a side job. They’ve also balked at Sewing’s decision to nominate Ilgner, who lacks banking experience, to the management board.

Investors say that Sewing has made important strides, including selling down unwanted assets and winning a nod from regulators to tap into the bank’s capital buffers to fund the restructuring. But walking back the revenue target dented his credibility. Most importantly, Sewing has yet to show he can bring in revenue and restore a competitive level of profitability to reverse the long decline in the stock.

“Sewing has filled some key leadership positions, but he hasn’t actually achieved much else yet,” says Michael Hünseler, a credit fund manager at Assenagon Asset Management in Munich. “The future of fixed income trading continues to be a crucial issue for the bank.”

Sewing supports the idea of European banks combining to help restore their profitability. But he also knows that, given Deutsche Bank’s current valuation, he would be the junior partner in any negotiation. So for now he’s left reversing the aggressive growth born in the era of global corporate expansion. As he prepares Deutsche Bank for a new phase of consolidation, driven by tougher regulation, Sewing has a last chance to get it right.

Arons is a reporter at Bloomberg in Frankfurt.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Christine Harper at charper@bloomberg.net, Christian Baumgaertel

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.