Death Bell Tolling for Private Colleges Sounds Bondholder Alarm

Death Bell Tolling for Private Colleges Sounds Bondholder Alarm

(Bloomberg) -- The challenges facing U.S. private colleges are starting to become their bondholders’ problem, too.

An unusual bankruptcy by New York’s College of New Rochelle this year will likely leave investors recovering only a fraction of what they are owed. A Christian college is asking bondholders to sell back their securities for as little as 10 cents on the dollar to help it emerge from a two-decade fight for survival. Others are defaulting on debt limits contained in bond contracts, a potential harbinger of deeper strife to come.

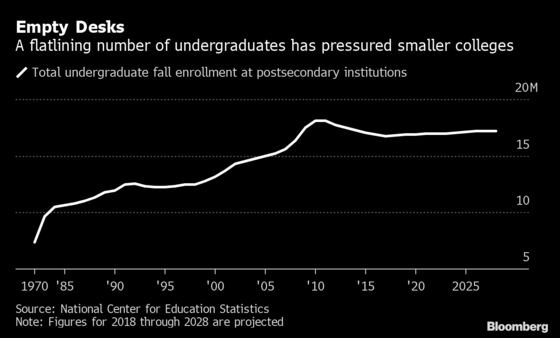

The troubles have been building at some small, private colleges for years as students grow apprehensive about taking on debt for costly tuition. Moody’s Investors Service has estimated that one in five such schools is under “fundamental” stress, and a demographic shift is threatening to make it worse: by one estimate, the number of high school graduates is projected to stagnate over the next several years and then start falling after 2026, threatening to increase competition for a smaller pool of students.

“The size of their market is shrinking,” said Joseph D’Angelo, a partner at Carl Marks Advisors, a firm specializing in debt restructurings. “If we were talking about a business or industry, we’d be going, ‘Oh wow, this is terrible.’”

The pressure is creating a divide in the higher-education system between the prestigious, wealthy schools that draw a large number of applicants and those struggling to attract them. Jessica Wood, a senior director at S&P Global Ratings, said she expects more colleges on the losing end to merge or shut down as a result. “I don’t think there’s an end in sight,” she said.

Ohio Valley University, in Vienna, West Virginia, is trying to avoid that. The approximately 500-student Christian school told investors that “tremendous market pressures” have left it facing an “uphill financial battle” for about 20 years. In June, it offered to buy back its debt for prices ranging from 10 cents to 40 cents on the dollar, depending on the particular security. In September, the school defaulted on debt payments.

Mike O’Neal, financial adviser for the college, said the school is still working on the restructuring and declined to comment further.

Bankruptcy

Still, out-of-court restructurings can be more advantageous to investors and the schools than bankruptcy, which is a last resort because it cuts off crucial federal student aid.

The College of New Rochelle in New York filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy this year. It will end up selling its campus for $32 million, which will cover a little more than a third of its outstanding liabilities. Investors who owned debt issued by Dowling College on Long Island, which went bankrupt in 2016, fared even worse: they recovered an average of 17.8% of what they were owed, according to Moody’s.

Others have been breaching the financial terms of their bond contracts. Bethune-Cookman University, a historically-black college in Florida, is negotiating with bondholders to avoid having to repay $16 million of debt early because of troubles tied to a costly dormitory project.

Such technical defaults can be remedied. Azusa Pacific University, a Christian college in California that has seen its credit rating slashed into junk, in 2018 reported that the difference between its revenue and its debt payments narrowed to a level below what it had agreed when it issued bonds. But Ross Allen, chief financial officer for the 10,000 student school, said it has instituted monthly budgeting practices and is using more conservative assumptions to constrain costs.

“This organization has turned around so quickly,” Allen said.

Join Together

The trouble has come slowly over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2017, not-for-profit private colleges saw enrollment grow by about 164,000 students, compared with a 440,000 increase during the previous decade, according to U.S. Department of Education statistics. At the same time, the steady increase in student debt has driven a push by Democratic presidential contenders Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders to make public colleges free, a step that would drastically reduce the draw of many private schools.

For those that can’t compete, mergers may be the only option short of shutting down. Yet they can be difficult to execute. After Mount Ida College in Massachusetts agreed to sell itself to Lasell College, for example, the deal was abandoned after bondholders reportedly balked at the initial terms It closed instead.

Marlboro College in Vermont may have better luck. Last month, it agreed to be sold to Emerson College in Boston, which will take over Marlboro’s $30 million endowment and real estate worth more than $10 million after the current school year. President Kevin Quigley said it was easier to negotiate a merger because it has an endowment that’s much larger than the $2 million loan it has with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“We just realized that we couldn’t make it on our own,” Quigley said.

It’s a lesson that shouldn’t be lost on others. Some colleges aren’t developing plans for attracting new students until it’s too late, said D’Angelo, the restructuring expert. “It should be obvious that you need to make some changes, and yet people are paralyzed,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Amanda Albright in New York at aalbright4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Elizabeth Campbell at ecampbell14@bloomberg.net, William Selway, Michael B. Marois

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.