Lone Doctor Fights Virus Raging at NYC Intensity in U.S. Black Belt

Lone Doctor Fights Virus Raging at NYC Intensity in U.S. Black Belt

(Bloomberg) -- Four years ago, a community group set two economic development goals for Lowndes County, Alabama: a new truck stop and a hospital.

The truck stop now sits off I-65 south of Montgomery. But Lowndes still pays $19,000 a month for a single ambulance to take the sick to emergency rooms a half hour or more away. A hospital remains an unreachable dream in a place with Alabama’s highest concentration of Covid-19 — and one of the worst infection rates in the U.S.

Lowndes County exemplifies the kind of region where the coronavirus continues to hunt: It’s rural, among the nation’s poorest, majority Black, rife with pre-existing illnesses and starved of health-care resources. It's the kind of place where a resurgence of the pandemic is taking root, as new infections rise in at least 21 states.

George Thomas, the county's sole doctor, said Lowndes became a coronavirus hot spot almost overnight. He suspects it was brought from Montgomery, where many of his patients work. “There are no jobs here, or very few,” he said during a break at his federally subsidized clinic in Hayneville that sits across a state highway from the Dollar General.

“It seemed like we sort of trailed behind for a long time,'' Thomas said. "But our numbers are really going up."

Covid-19 races through families in cramped mobile homes, the county’s main housing stock. “What makes it worse in Lowndes is that the person who gets it doesn't have anywhere else to go,” said County Administrator Jacquelyn Thomas.

Lowndes now has an infection rate that rivals the most infected zip code in New York City at its pandemic peak. By last week, more than a third of the tests in Lowndes had come back positive. The few people out in Hayneville's two-block downtown wear masks even in cars. The sign at Mt. Zion AME Zion Church: ``God will see us through. Stay safe."

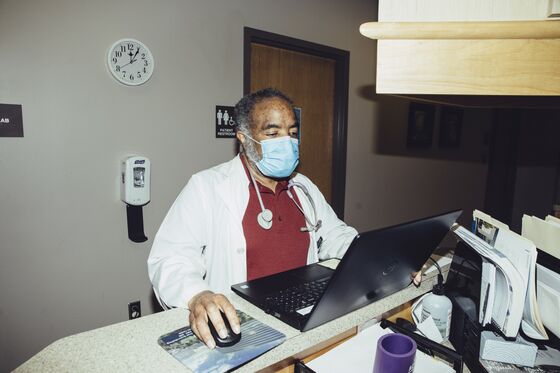

Thomas, 64, has been serving Lowndes County for decades out of Hayneville Family Health Center, one of 13 operated by Health Services Inc., based 30 minutes away in Montgomery. Thomas sees patients there until 4:30 p.m. every weekday, then at a Montgomery clinic until 10 p.m. The county’s 9,726 residents have no doctor on nights and weekends.

The doctor has embraced telemedicine, but Internet service is so bad that the clinic relied on a staffer's mobile hot spot to get virus test results into its computers: "Even then, it had to be at a certain angle to work," Thomas said.

In recent weeks, patients from Lowndes and overwhelmed hospitals in nearby Selma and Greenville swamped Montgomery’s Jackson Hospital, a two-block compound licensed for 344 beds that functions as a kind of safety valve for rural counties with little hospital capacity. Jackson had only one intensive care bed at one point, and some patients had to be moved an hour north to Birmingham.

“It doesn't take a lot of patients to cause a health-care crisis in a small community with no hospital,” said Eric Toner, a senior scholar at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Health Security. “You don't need to see New York-level outbreaks.”

Alabama’s health care was already stressed. In addition to scarce Medicaid dollars for the poor, rural providers who care for the elderly get the lowest Medicare reimbursements in the U.S., mirroring regional wages. The state has lost seven rural hospitals since 2010. When Covid-19 hit, 88 percent were in the red, according to the Alabama Hospital Association.

The virus bared disparities, said Thomas Tsai, a surgeon and policy researcher with the Harvard Global Health Institute. The rural U.S. is “both a desert in terms of access and a desert in terms of the quality of care.”

The pandemic has been particularly deadly for African-Americans, who are dying at 2.4 times the rate of whites. In majority-Black counties in the U.S., the rate is more than triple the national average, according to a Bloomberg News analysis of Johns Hopkins and Census Bureau data. Among Black communities in the rural South, the picture gets worse, because of poverty and -- critically -- the lack of Medicaid expansion, according to Karen Joynt Maddox, a cardiologist and health policy professor at Washington University in St. Louis. People without insurance are less likely to get treated, tested or tracked, which starts a “cascade,'' Maddox said.

Alabama is among Southern and Western states offsetting national declines in new cases, according to Pantheon Macroeconomics, which puts out a daily Covid-19 update. Alabama's percentage of positive tests was 12.5% last week and rising.

The rise in rural infections -- also happening in Texas, Arizona and Florida -- marks a shift, said Toner of Johns Hopkins, after experts initially saw Covid-19 as “primarily an urban event.”

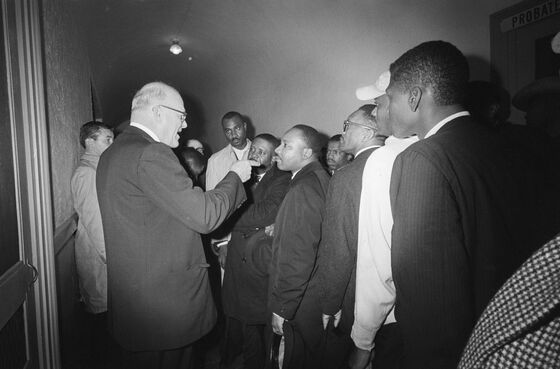

Lowndes is decidedly not urban. It sits in the Black Belt, a region originally named for its rich soil and later for its majority population. The Black Belt’s boundaries aren't formally defined, but it's generally accepted to stretch from its Alabama center east into Georgia and west into Mississippi. Its economy historically depended on cotton plantations and slavery.

The county is steeped in civil rights history. It was a halfway point in Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery. Black power advocate Stokely Carmichael organized voters there in the 1960s, often with violent opposition that spawned the nickname Bloody Lowndes and inspired Carmichael's Black Panther Party.

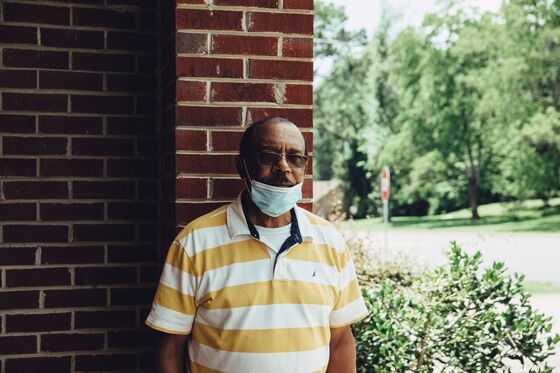

Today, Lowndes County is 72 percent African-American, and more than a quarter of its residents live in poverty. The average per capita income is $19,491.

The coronavirus has hit the Black Belt hard. In Georgia, the 14 counties with the highest Covid-19 infection rates are all in the region. In Alabama, it’s seven of the worst 11 counties.

Covid-19 got to Lowndes after hitting Alabama's cities, then poultry plants and prisons, said State Health Officer Scott Harris. In Lowndes, “Covid-19 just highlights the problems they have had for years,” he said.

Among them: Lowndes has had the state’s highest rate of HIV infection since 2010, more than triple the national average. Thomas’s Hayneville clinic sees malnutrition, low birth-weight babies and a lot of hypertension and diabetes, both of which raise the risk of serious illness or death from Covid-19.

Still, when the pandemic arrived, residents "didn't take it extremely serious,'' said David Daniel, Hayneville's mayor. People ignored social distancing and didn't wear masks until a little more than two weeks ago, when infections spiked. "Now that it is somewhat on a rampage here, you'll see most of them are wearing masks."

At Lily Missionary Baptist Church in Letohatchee, another Lowndes County town, pastor Fletcher Fountain now preaches on Sunday to a congregation parked in their cars, but says residents still aren’t careful enough. “There's probably a lot more people that have it than we know,” he said. “We just don’t have enough health services here for the whole county.”

Policy changes -- including Medicaid expansion -- could improve matters, said Gilbert Darrington, chief executive of Health Services Inc., the Montgomery operator of the Hayneville clinic and others that offer care on a sliding scale.

The Hayneville clinic does “a bang-up job'' serving both the uninsured and the insured, said Darrington. But its hours are limited and it can't provide specialized services for people with heart problems, cancer or Covid-19. It can't force people working long hours outside the county to make time for check-ups, a problem that has only gotten worse in the pandemic: The Hayneville clinic has seen a 40 percent drop in patients. It also can't pay for medicine.

“Had the state expanded Medicaid, I'd write a prescription and know it might actually get filled,” said Thomas.

The dream of a Lowndes hospital, meanwhile, isn't dead.

Ozelle Hubert, a pharmacist whose group pushed for it four years ago, is still at it. He says a Mississippi hospital chain is interested and lists a range of money-making services -- including treating prison inmates and providing ambulances -- that might overcome the daunting economics. Thomas is doubtful, but says a telemedicine center linked to doctors in Montgomery might work -- assuming the Internet connection improves.

Darrington's desire is more modest: "It would be very beneficial just to have two more ambulances on hand."

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.