Contact Tracers Eye Cluster-Busting to Tackle Covid’s New Surge

As a resurgent coronavirus sweeps across Europe and the U.S., some health experts are calling for a “cluster-busting” approach.

(Bloomberg) -- As a resurgent coronavirus sweeps across Europe and the U.S., some health experts are calling for a “cluster-busting” approach to contact tracing like the one Japan and other countries in Asia have used with success.

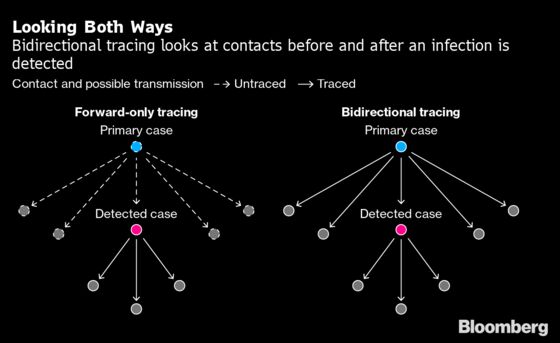

Rather than simply tracking down the contacts of an infected person and isolating them, proponents advocate finding out where the individual caught Covid-19 in the first place. That extra step, known as backward tracing, exploits a weak spot of the virus — the tendency for infections to occur in clusters, often at super-spreading events.

KJ Seung, a doctor who helps oversee contact-tracing for Massachusetts, said he adapted his approach this summer after watching a seminar with Japanese scientists. Since his team started backward tracing, they’ve uncovered clusters at weddings, funerals, bars and other places where people congregated, generating fresh insights into the spread of the disease.

“It’s been eye-opening,” said Seung, an infectious disease specialist with Partners in Health, a Boston-based non-profit group hired to help implement the state’s contact-tracing program. “You can discover more cases, more efficiently.”

The approach has implications for policy makers, who are again imposing costly lockdowns across much of Europe and parts of the U.S. after containment strategies that relied on existing testing and tracing largely failed. The message from health officials like Seung and Japan’s cluster-busting proponents is to take heart and press on; there’s room for improvement.

“This virus is controllable,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, head of the World Health Organization’s emerging diseases unit, who considers clustering a hallmark of coronaviruses. “The trajectory is completely in our hands.”

Tracing infections back to the source isn’t new. It’s standard practice for managing sexually transmitted diseases, like HIV and syphilis. But those conditions aren’t prone to super-spreading. And when it comes to respiratory infections, most European and U.S. officials tend to think in terms of the flu, which often doesn’t spread in clusters either.

Debates over the merits of basic precautions like mask-wearing and social distancing have also hampered efforts to fully grasp Covid’s clustering phenomenon, said Zoë McLaren, a public health policy professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Most Western countries came into this year with insufficient contact tracing expertise and, when they built up their teams of Covid tracers, focused primarily on chasing infections in the forward direction. There is a logic to that. Because individuals are often capable of spreading the virus a couple of days before the onset of symptoms, tracers ask people whom they might have infected over that stretch, in hopes of catching other cases early and preventing further spread.

The problem with Covid-19 is that a relatively small proportion of those who are infected will transmit the virus, according to some studies. So contact tracers spend a lot of time locating people who were probably not infected.

With backward tracing, officials go deeper into someone’s recent past — as much as two weeks — to determine when and where the infection took place. If transmission occurred in a group setting — especially indoors, with talking or singing and poor ventilation — the chances are good that others were also infected. By zeroing in on those people, health officers can improve the odds of finding infectious individuals, and then begin forward tracing with those people.

“If 80% of cases do not transmit, then 80% of cases where you are forward tracing contacts are wasted effort,” said William Hanage, an epidemiologist at Harvard School of Public Health. “Because you know transmission occurred in the backward tracing, the marginal benefit is greater.”

Some Western scientists saw Covid’s clustering tendency early on. Franz Wiesbauer, a doctor and epidemiologist who runs Medmastery, a training service for medical personnel in Salzburg, Austria, cited studies in May pointing out that as few as 10% of people in certain places appeared to cause as many as 80% of infections.

“If we can just limit those events that cause super-spreading, we can ease other measures like gatherings outside,” Wiesbauer said. But, five months on, the West still hasn’t gotten the point, he said. “It’s so frustrating.”

In Asia, where countries have suffered in recent decades from cluster-prone diseases like tuberculosis and SARS, that message gained better traction.

South Korea throttled a big super-spreading event in February and March with mass testing and extremely fast forward tracing. Taiwan hasn’t had a locally transmitted case in more than 200 days — thanks to closing borders and tightly regulating travel, as well as rigorous tracing and quarantine measures.

Japan is a particularly useful example for the West, since it hasn't relied on much Covid testing nor the mass collection of people's private information. The country did, however, set up a task force in February that focused on identifying clusters and stamping out widespread transmission, rather than trying to track down each individual case. The country relied on a large network of local health officers, too, who already had years of experience with contact tracing, both forward and backward, in combating tuberculosis.

“The cluster formation is probably one of the most important epidemiological characteristics” of the coronavirus, said Hitoshi Oshitani, a professor of virology at Tohoku University and a key architect of the government’s strategy.

Japan has reported just over 100,000 Covid-19 cases since the pandemic began, less than one-tenth of the number in France and Spain, which have smaller populations. The U.S. has recorded more than 9 million infections. Fatalities in France increased by 854 on Tuesday, the most since mid-April, to 38,289. Japan has had fewer than 1,800 Covid deaths in total, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University.

As infections surge in the U.S. and Europe, some fear societies will scrap contact tracing altogether. That's because so many countries have struggled to fully implement basic measures, from physical distancing to widespread mask wearing to a coherent strategy that ties together testing, tracing and isolating people.

White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows said last month the U.S. was “not going to control” the pandemic, and would concentrate on developing “vaccines, therapeutics and other mitigation areas.”

Even Germany, widely praised for its tracing program last spring, has seen positive cases balloon to records, and imposed month-long restrictions on public life.

One hurdle to backward tracing is that people don’t always recall the risky situations they were in a week or two ago, said Christian Drosten, head of virology at Berlin’s Charite Hospital, on a recent episode of his podcast. Since early August, he has been calling on Germans to keep a daily journal of their contacts.

“We can’t just say, ‘we’re totally passive here, the health authorities will figure it all out if I get sick,’” he told his listeners.

Seung has battled infectious diseases for almost two decades since joining Partners in Health in 2001, including HIV in Lesotho and tuberculosis in Peru and North Korea. Since making backward tracing part of his strategy against Covid, he’s begun promoting the approach to other U.S. states, offering a mix of technical advice and emotional encouragement. It takes time for tracers to master the technique, but that's all the more reason to get started, he said.

“The idea that you shouldn’t do contact tracing in a surge of cases, that’s not really a good attitude,” he explained.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.