Colleges Weigh Scrapping Football Season in Threat to a Cash Cow

Colleges Weigh Scrapping Football Season in Threat to a Cash Cow

(Bloomberg) -- It’s the toughest call in sports this year: to play or not to play.

Colleges across the U.S. are assessing the spread of Covid-19 to determine whether students should return to campus in the fall, and many schools must also decide whether it’s safe to resume football, a cash cow for some big schools and for the surrounding college towns.

That determination will have a financial impact on athletic departments for years to come, said Willis Jones, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Kentucky.

“Schools will put off that decision until they have absolutely no other choice,” said Jones, who researches intercollegiate athletics. “Once there is one that’s brave enough and says ‘We can't do this and still protect our student athletes,’ I think other schools will follow.”

That’s what happened in March after the Ivy League canceled its basketball championships to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus. A few schools have recently scotched fall sports, including the Maine liberal arts college Bowdoin on Monday and the 13-member California Collegiate Athletic Association in May. Their decisions could embolden cancellations at larger schools, and at small schools where football is a big part of campus culture and is key to enrollment.

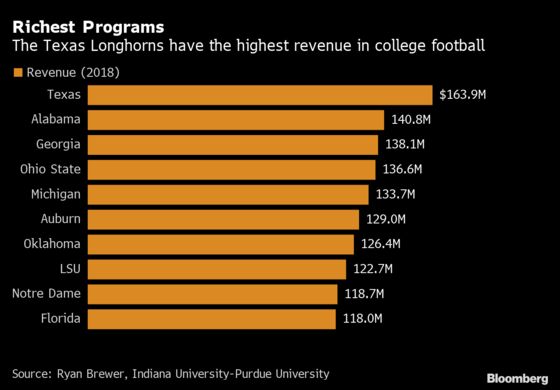

Schools that bring in the largest revenue from football that responded to Bloomberg’s questions, including the University of Notre Dame and the University of Georgia, are still making decisions and planning for a season. At Notre Dame, where football revenue accounts for less than 7% of its $1.7 billion operating budget, “health and safety considerations trump stadium revenue,” said Paul Browne, a spokesman for the school in South Bend, Indiana. Georgia’s call will be made with the advice of medical officials and guidance from the conference’s leaders, the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the governor and school officials.

At the professional level, the National Football League has canceled off-season training programs and, with the exception of injured players undergoing rehab, kept its facilities shuttered. The league plans to start its training camps this summer, albeit under strict testing protocols. Not all players have heeded the league’s guidance. The Tampa Bay Times reported this week that Buccaneers quarterback Tom Brady recently gathered about a dozen of his teammates for a non-sanctioned workout at a local high school despite multiple members of the organization having tested positive for the virus.

For universities deciding how to proceed, there is at least some precedent this time, unlike three months ago when administrators faced a similar challenge as the virus spread in the U.S. The Ivy League – not exactly an athletics powerhouse – was the early mover, and hundreds of schools quickly followed by canceling spring sports to limit contagion. Some basketball tournaments were under way, with games being played in the Big Ten and Atlantic Coast and Big East conferences, according to an analysis by Christopher Marsicano, a visiting assistant professor of educational studies at Davidson College.

The Ivy League, whose eight schools include Harvard, Yale and Princeton, scrapped its conference championships on March 10. The games were to be hosted at Harvard in Massachusetts, an early hotspot for the coronavirus in the U.S.

“In the four days that the league discussed what to do with spring sports, diagnosed cases in Massachusetts went from 13 to 28 to 42 to 91, clearly an exponential growth curve, albeit starting from a small base,” Harvard’s president, Lawrence Bacow, said by email in late April. “I had my experts telling me it was not safe to bring large groups of people from around the country together under the circumstances.”

The Dominoes Fall

On March 11, the Ivy League also canceled spring sports. By the following day, 190 more Division I athletic programs that had pending championship games had canceled their own tournaments, including one in the Big East held at Madison Square Garden that was halted midway, Marsicano said. The NCAA also canceled its March Madness basketball tournament on March 12.

The decisions illustrate how colleges respond to crisis.

“Once the Ivy League canceled its tournament, both Duke and Kansas, with big massive programs, decided not to play basketball on March 12, leading the dominoes to fall,” said Marsicano, who directs the College Crisis Initiative, which has examined data about college response to Covid-19.

The Ivies could afford to act first. For the wealthiest universities, canceling spring sports did not feel like a make-or-break budget decision as it seemed to be for many Division I schools.

“The revenue, when it comes, is nice, but it’s not the rationale, the driving force behind the decision,” said Robin Harris, the Ivy League executive director since 2009. “It was about the right thing to do.”

The league formally began contingency planning on March 6 with its first call on March 8, according to Harris. The eight presidents spoke by phone four times over the course of the decision-making process. The schools each had proxies meeting separately; Harvard’s was provost Alan Garber, a physician and an economist who has written about managing epidemics.

They didn’t immediately shut down sports. The aim as of March 9, a Monday, was to hold the tournament, but with limited fans, on its scheduled dates, beginning March 13.

“If we acted prematurely, we would inconvenience a lot of people, disrupt the lives of our students, faculty and staff needlessly and their parents. We would also squander a lot of resources,” Bacow said. “However, if we did not act and we were wrong about the public health crisis we were facing, people could die.”

The reaction, especially from athletes, was harsh.

“We took some shots, and that's fine,” said Peter Pilling, Columbia’s athletics director. “I don't think we were going to apologize for what we did, and at the same time, we're not going to take any gratification from how it ended up.”

The Money Factor

At big schools outside the Ivy League, the decision in the spring was complicated by the prospect of losing out on revenue from TV deals, as well as ticket and merchandise sales for the remainder of the basketball season. The decisions facing football schools now are also tangled up with revenue concerns.

“The TV money from football is a very big deal for a lot of these schools,” said Chuck Staben, a former president of the University of Idaho. “They're going to be highly motivated to have a football season.”

When the University of Alabama plays at home, there's an average statewide economic impact of almost $25 million per game, according to a 2017 university study.

“I am firmly of the belief that money drives the decisions made in sports today,” Senator Chris Murphy, a Democrat of Connecticut, said in an interview about colleges. He expressed concern about student athletes contracting the virus.

Mitch Daniels, the former Indiana governor now president of Big 10 member Purdue University, talked about athletics in a Senate hearing this month. The school is planning for 25% capacity in its football stadium and could adjust that.

Notre Dame says that conditions severe enough to keep the campus closed, like a wider-scale outbreak, would also preclude fall sports. “If we do not have students on campus, we will not bring our student athletes to campus,” said Browne, the spokesman.

The University of Georgia is planning on a regular season and hoping for a full stadium, but will have contingency options, said Claude Felton, senior associate athletic director.

“We have two and a half months to go before the first game, so there is no urgency to make any decisions at this time,” Felton said. “We will continue to monitor all developments as we learn more every day.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.