The U.S. College Admissions Scandal Is So Post-Soviet

The U.S. College Admissions Scandal Is So Post-Soviet

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.S. college admission scandal that broke Tuesday feels extremely Soviet, and not just because one of the people accused of helping students cheat on standardized tests, West Hollywood prep school director Igor Dvorskiy, is an ex-Soviet immigrant. The motives behind American parents’ determination to get their children into the right schools are similar to those of post-Soviet parents, and that should be disturbing to Americans, including policy-makers.

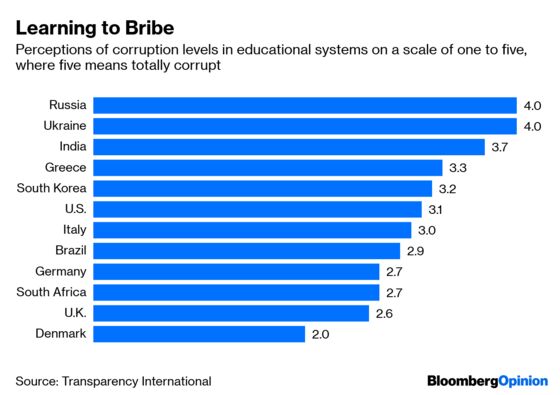

According to anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International, 38 percent of Ukrainian households and 29 percent of Russian ones reported in 2017 that they’d paid a bribe while accessing the educational system in the previous 12 months. A lot of the bribery is concentrated in the admissions process. People rig the standard tests, they hire professors from the chosen university to give private lessons to their kids, and they directly bribe admissions officers.

Post-Soviet and generally post-Communist countries have a lot of academic corruption (and attract the most attention from researchers into the phenomenon) because of the power of informal networks, which matter more in these countries than academic achievement. “All my friends are from my school years, from university or from previous jobs,” Russian President Vladimir Putin once said. After Putin came to power, these friends quickly started getting rich, powerful or both. Gaining admission to the same school as the next Putin can guarantee a successful career and access to opportunities not available to less-lucky mortals. It’s less important how you get in and how well you do than what relationships you build. The returns to these relationships can be enormous.

In countries with stronger formal institutions, perceptions of the importance of old-boy networks may be widespread, too, but there’s less solid evidence that these networks are as powerful as they once used to be. In the U.K., for example, a so-called class pay gap still exists: People from privileged backgrounds, who attend private schools before university, tend to make more a few years after graduation than graduates from the same universities but from more modest families. But recent attempts to disaggregate the effect have found that access to high-value networks, which is indeed much higher for private school students, has pretty much no effect on earnings later in life. What does have an effect is the higher quality of education in the private schools.

In the U.K., then, privilege plays an especially important role at the pre-university level. That’s also the case in Germany, where the traditional Prussian school system — which still underlies German education despite all attempts to modernize it — sorts children into vocational, technical and elite tracks extremely early in their studies. In such systems, admissions corruption makes little sense. Educational advantages and what’s left of old-boy networks are formed at an earlier stage.

In terms of corruption perceptions, according to Transparency International, the U.S. education system occupies a middle ground between those of Western European and post-Communist countries.

That should give Americans pause. What is it about the specific U.S. type of inequality that puts this kind of stress on the education system? Could it be the Soviet-style perception that a student’s informal network, formed in the college years, is more important than the actual education he or she receives?

If so, two factors could be at play: The popular concept of human capital, according to which a student (or the student’s parents) are making an investment as if in a business (and then the right network could mean more than any kind of intellectual achievement), and what Thomas Piketty called the “hypermeritocratic” system, whereby a small number of Americans enjoy wildly unequal remuneration for their labor. In “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” Piketty wrote:

The top 1 percent (and even more the top 0.1 percent) have seen their remuneration take off. This is a very specific phenomenon, which occurs within the group of college graduates and in many cases separates individuals who have pursued their studies at elite universities for many years.

Education systems perpetuate privilege and elites in other cultures, too; in Germany, for example, there’s evidence that students from the higher social classes get a disproportional number of supposedly merit-based scholarships. What differentiates the U.S., however, is the approach to the college years as a source of social capital rather than a path toward professional qualifications — and the chance at abnormal remuneration. The two factors combine to create an incentive to cheat at the admission stage that’s absent or weaker in other countries.

More income equality and a focus on intellectual development rather than networking could be helpful in eliminating corruption in education both in post-Soviet countries and in the U.S. As things stand, they have too much in common.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.