Climate Change Is Reshaping Atlantic Fisheries and Sending This Fluke Fight to Court

Climate Change Is Reshaping Atlantic Fisheries and Sending This Fluke Fight to Court

(Bloomberg) -- By his own account, Anthony DiLernia is a guy who can make friends with any angler. For 45 years he’s run a fishing charter boat out of New York Harbor, and he’s served as a member of the Mid-Atlantic Fishing Council on and off for almost as long.

But get DiLernia on the subject of Paralichthys dentatus, aka summer flounder, aka fluke, and his voice gets territorial in a harbor kind of a way. What steams him are the wide variances in the amount the fish the federal government permits each state to catch. The uneven allocations are the reason that Southern fishermen routinely travel hundreds of miles to the waters off Long Island to trawl for fluke that local fisherman are forbidden to catch.

These state quotas, which are meant to prevent a species from being fished out of existence, are based on patterns of where the fish were brought in to docks in the 1980s. Back then summer flounder were clustered off Cape Hatteras, which explains, in part, how Virginia and North Carolina together get more than 50% of the annual quota, whereas New York gets only a little more than 7%.

But anyone who spends any time with a net knows warming waters have been pushing fluke steadily north. “You know all those critters who used to live down South? Guess what? They’ve moved to the Bronx,” DiLernia said.

“Our guys will be fishing right along their guys 80 miles off Long Island,” he said with indignation rising in his voice. “We catch more than a couple hundred pounds, and we have to throw the rest back—which is a total waste. Meanwhile, they are filling their freezer and driving back to North Carolina. With diesel fuel. What do you think that does to the environment?”

In October, urged on by DiLernia and other fishermen, New York sued the U.S. Department of Commerce to get the right to fish for a greater share of fluke. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which administers the quotas, is a division of the department. The lawsuit is awaiting the assignment of a judge, according to the New York State attorney general’s office.

Disputes over fish quotas are not new, and the $25.2 million East Coast market for fluke—although a reliable bread-and-butter fish—is not particularly lucrative. And New York has sued to alter the quota before. But this lawsuit is being watched closely because it introduces a new factor into the decades-old quota system: the impact of climate change.

Quickly warming waters have reshaped the entire fishing industry on the East Coast, moving the fluke dramatically to the north. The lawsuit argues that now 80% of all fluke catches occur within 150 miles of Long Island and that state allocations need to be updated to reflect the fishes’ evolving location.

It’s the first lawsuit about fish allocation to be sparked by climate change —and it could have a profound impact on a $212 billion national industry, said Susan Farady, a professor of marine affairs at the University of New England.

The reason, she said, is that the lawsuit essentially challenges the rigidity at the heart of the current system. “We’ve got this management system that was developed for relatively stable geographic distribution of fish,” Farady said. “It’s a delicate glass slipper mold, and it’s just not a good fit anymore.”

In the 1970s the U.S. instituted a complex management system that is part science and part politics. Commercial fishermen are allowed to fish for only a certain amount of any given species, and they’re required to disclose what they bring to shore. The result is one of the great success stories in conservation: U.S. fisheries are among the healthiest in the world.

But the strength of the system—an enforceable set of quotas based on where fish live—is turning out to be a vulnerability as waters warm and fish move. Lisa Suatoni, the deputy director of the oceans division at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the people designing the system “never contemplated anything but stasis.”

The system works because federal scientists monitor individual fish stocks, set a cap on the number of fish that can be caught, and divide up the haul for each species by region. There are nine regional fisheries councils to help with management, each sharing in the responsibility of allocating the quota for fish that had historically swam in their waters.

In the case of fluke, the catch limits for each state were made by evaluating sales receipts fluke fishermen provided in the 1980s. But back then waters between Massachusetts and North Carolina were on average 4 degrees Fahrenheit cooler.

John Ewald, a NOAA spokesman, said the agency does not comment on litigation matters. But Vince Saba, a research fishery biologist at NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center, said the agency knows there is climate change and that it’s changing ocean habitat at an unprecedented rate. In other words, there is stasis no more.

Malin Pinsky, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Rutgers University, does marine species modeling in conjunction with NOAA. “Marine species are cold-blooded, so they tolerate a relatively narrow range of temperatures and oxygen. So the redistribution of these species is happening much faster in the ocean, sometimes 10 times faster than on land,” he said.

Atlantic coastal waters are warming even faster than other parts of the ocean, which has been particularly hard on fish that like colder water such as fluke, he added.

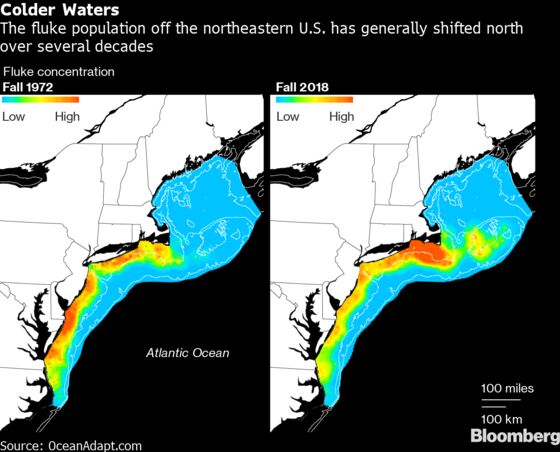

Pinsky has built interactive maps that show how fish move over time. One chart assesses the highest concentration of fluke from 1972 to 2018. It’s easy to see the red blob signifying the densest cluster starting off the Virginia coast and moving north to swell in Long Island waters and then trickle up as far north as New Hampshire.

He said that as long as the total quota numbers aren’t being exceeded, he feels satisfied that the species are being sustainably fished.

“The next question is, how do you allocate fish equitably and efficiently? Here there is a big disconnect,” he said.

The equity and efficiency are what’s at stake in the lawsuit—and the idea that New York fisherman should get to catch fish found off the coast of New York is harder to implement than it might seem.

Mike Luisi, an official with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Fishing and Boating, and the current chairman of the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, doesn’t dispute that the fish are moving. “It’s what exactly to do about it that gets complicated,” he said.

States that have historically had large allocations have built a lot of corresponding infrastructure—some of it that’s very species-specific—that cannot readily be moved around. “It’s everything from boats, to special types of gear, to the plants that process the fish,” he said.

“My stakeholders in Maryland don’t want me to give up one ounce of fish, even if stocks are shifting,” Luisi said. “They are willing to take their boats wherever the fish are.”

And as the fish continue their migrations northward, New York is not the only state that wants in on Southern fish. Rhode Island is formally requesting a seat on the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council in part because so many of the fish that now come up in their nets aren’t included in the state’s quota.

For now the council is giving New York a larger percentage of any of the increase in fluke allocations that come if scientists assess the subspecies to be particularly robust. But several experts from conservation organizations are concerned that moving too slowly will have repercussions.

NRDC’s Suatoni said her group worries that there will be pressure to loosen restrictions and allow everyone more fish. This would put additional stresses on the stocks. “The second concern is when people feel the regulatory system is failing them, they feel compelled to cheat,” she said.

In fact, New York fisherman have already been caught cheating in one of the largest fishing investigations in U.S. history. Even back in 2010, New York had been complaining about its fluke allocation and the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council allowed New York to catch more with one condition: Fisherman were supposed to keep track of their sales from the extra quota and return a percentage to NOAA to fund scientists.

But a handful of fishermen violated the quota in a big way—and got caught by NOAA’s Office of Law Enforcement. Anthony Joseph, a commercial fisherman from Levittown, N.Y., was found guilty in 2015 of having taken 302,000 overages of fish over the course of 158 trips and having falsified records to cover it. He was one of seven individuals and four companies that were charged.

NOAA’s Saba said he and his team understand that fisherman are frustrated. “Ideally, we want to move to a climate-ready management system,” he said. “But at this point it is happening so fast that we just don’t know how yet.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Emily Biuso at ebiuso@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.