China Eyes Quick and Loose Carbon Market Start as Deadline Looms

China Eyes Quick and Loose Carbon Market Start as Deadline Looms

(Bloomberg) -- In a rush to start the world’s biggest carbon market, China is looking to have a more lax approach to emissions rather than cut greenhouse gases in the short-term.

Under pressure to start a national carbon trading system that aims to force power firms to pay for their emissions by the end of the year, policy makers are proposing looser restrictions that are more likely to get companies on board while kicking the can down the road on how to tighten those limits.

The latest proposal offers power companies participating in existing regional pilot programs more generous allowances to emit carbon in the new market, and lets their local governments opt out of the national system for the first year, Bloomberg News reported earlier, citing people who saw the draft plans. The softer approach signals China will be less aggressive about phasing out coal in the short-term as the coronavirus makes shoring up economic growth a priority.

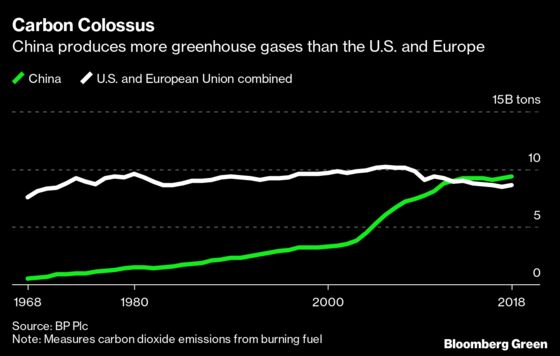

China said in 2017 that the national market was expected to cover more than 3 billion metric tons of carbon emissions, almost double the 1.6 billion tons covered by the European Union’s market last year. The world’s second-biggest economy produced more than 9.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide in 2018, greater than the U.S. and Europe combined, according to data from BP Plc.

“The lenient targets might reflect the desire of policy makers for a swift start” in China, said Jeff Huang, chief executive officer of Hong Kong-based energy trading firm AEX Holdings Ltd. “I expect the national cap would be tighter and tighter as time goes by.”

Looser Rules

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment, which is in charge of developing the carbon market, is eager to start trading this year to show China’s serious about its commitment to the Paris Agreement on climate change, according to government researchers familiar with the discussions who asked not to be identified as they’re not authorized to speak to the media. The ministry didn’t respond to a request for comment.

China is on its way to achieving its Paris Agreement pledge of cutting carbon emissions as a proportion of gross domestic product by at least 60% from its 2005 level by 2030. Top officials are also considering accelerating the adoption of clean energy. However, neither of these goals will reduce the absolute amount of China’s greenhouse gas emissions -- more than 25% of the global total -- as the country’s energy use continues to grow.

The latest plan allows China’s eight most-industrialized regions, where the pilots are now being run, to opt out of the national system for the first year. It also allocates more generous allowances to smaller companies that have hardest hit by the virus.

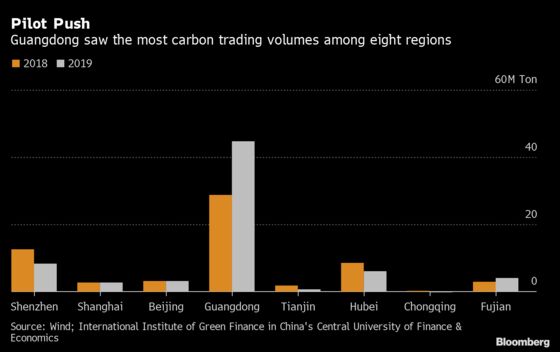

For example, a small coal-fired power plant would get 17% more initial allowances under the national proposal than it would have received under 2019 quotas in Guangdong, the southern industrial powerhouse where nearly 40% of China’s existing carbon trading takes place.

Pilot Programs

How to integrate those pilots into the national system is a major sticking point between the government and industry.

The proposed plan could persuade more power firms in the pilots to join the national market because they would get more carbon allowances, according to Zheng Jiangzhuo, head of technology at Kingeta Group, which provides services including carbon trading. It would also result in a glut of quotas, making it harder for the pilots to induce emission cuts while allowing firms that do join the national platform to relax their emissions standards, he said.

“A better way would be tightening allocations in the national market relative to this plan, along with some adjustments in local pilots, and providing a short transition time from local pilots to the national market,” he said.

The environment ministry’s latest plan also closes an arbitrage window that would have allowed permits acquired in the pilot markets for 2019 and 2020 to be converted and sold in the national system. That’s frustrating traders who saw an opportunity to profit from selling their permits to new entrants to the national platform, according to a manager at a power firm based in Guangdong who asked not to be named discussing the proposal.

Companies in the pilots paid between 18 yuan ($2.70) and 95 yuan per ton of carbon in the third week of September. Traders in a survey published by the China Carbon Forum in December said they expected the national price to start at 43 yuan per ton and rise to 75 yuan per ton by 2025.

“A smooth transition from regional pilots to national market is critical for securing the continuous support and trust of the market participants,” said Lina Li, China coordinator at the International Carbon Action Partnership, an intergovernmental organization focusing on market implementation worldwide. The group expects that the pilots and national system will co-exist in the medium term.

Many Hurdles

The ultimate prize -- getting coal plants to shut because operations become unprofitable -- will only be within reach when prices get high enough, and the government hasn’t indicated if and by how much it plans to tighten allowances in the future.

“It will be difficult for this new emissions trading system to push existing coal plants to an early retirement unless regulators tighten the allowance allocation,” said Yvonne Liu, a Beijing-based analyst at BloombergNEF.

The European Union faced similar growing pains when it developed its own carbon trading system, currently the largest in the world and a model for China. European carbon prices only began a sustained rise 13 years after the market was created, when investors piled in and government officials made clear they were determined to set an ambitious emissions-reduction goal.

Like the EU, China relies on companies to disclose their own emissions, which it isn’t able to verify. While China has a nationwide network of radars that track real-time emissions of sulfur dioxide and other pollutants, they don’t detect carbon dioxide. Local government budgets, strained by the virus, can’t always afford third-party services to verify data submitted by emitters.

If the market does work and carbon prices start rising, there’s a chance some of the cost will have to be passed on to consumers, a concern that has stymied the environment ministry’s efforts to establish the emissions trading system. China has cut power prices for end users repeatedly over the past three years as economic growth slowed, and lowered them further during the pandemic.

“The draft design shows China lacks the political will to add high carbon costs to coal and gas users,” said Li Shuo, a senior global policy adviser at Greenpeace in Beijing. “The proposal will also have to be reviewed by other ministries, so the final result may be even weaker.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg