Central Banks Are Creating a Horde of Zombie Investors

Central Banks Are Creating a Horde of Zombie Investors

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Ruchir Sharma, chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, wrote a provocative op-ed in the New York Times last weekend. Titled “When Dead Companies Don’t Die,” it argues that unprecedented monetary stimulus from global central banks created a “fat and slow” world, dominated by large companies and plagued by a swarm of “zombie firms” — those that should be out of business but survive because of rock-bottom borrowing costs.

I would add that central bankers are creating a horde of zombie investors as well.

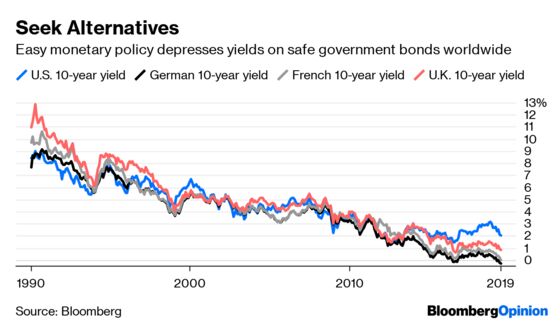

By now, bond markets have adjusted to the unabashedly dovish shift from European Central Bank President Mario Draghi and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell. In the U.S., benchmark 10-year Treasury yields fell below 2% for the first time since Donald Trump was elected president, and some Wall Street strategists expect it’ll reach a record low around this time in 2020. Across the Atlantic, 10-year German bund yields plumbed new lows of negative 0.33%, French 10-year yields hit zero for the first time, and the entire yield curve in Denmark was on the cusp of turning negative.

With any sort of risk-free yield largely zapped worldwide on the prospect of further monetary easing, is it any surprise what happened next? Investors turned to the tried-and-true playbook of grabbing anything risky. No matter that the global recovery has lasted nearly a decade, trade concerns abound and central banks see economic weakness — the S&P 500 Index promptly rose to a record high as investors mindlessly plowed in. And in a more specific example highlighted by my Bloomberg Opinion colleagues Marcus Ashworth and Elisa Martinuzzi, bond buyers were all-too-eager to snap up subordinated Greek bank debt from Piraeus Bank SA, which tapped European capital markets for the first time since the financial crisis. “The offer would have been unthinkable a year ago,” they wrote.

Are these really the characteristics of healthy financial markets? It hardly seems ideal that individual investors, pensions and insurers are effectively forced into owning lower-rated bonds, equities or even alternative assets like timber to meet their return targets. In fact, that sounds like the textbook definition of a bubble. But as Sharma points out, permanently easy policy aims to create an environment in which those bubbles can’t pop.

“Government stimulus programs were conceived as a way to revive economies in recession, not to keep growth alive indefinitely. A world without recessions may sound like progress, but recessions can be like forest fires, purging the economy of dead brush so that new shoots can grow. Lately, the cycle of regeneration has been suspended, as governments douse the first flicker of a coming recession with buckets of easy money and new spending. Now experiments in permanent stimulus are sapping the process of creative destruction at the heart of any capitalist system and breeding oversize zombies faster than start-ups.

To assume that central banks can hold the next recession at bay indefinitely represents a dangerous complacency.”

Time and again, market watchers will warn that the credit cycle is on the verge of turning. “The future looks pretty bleak,” Bob Michele, JPMorgan Asset Management’s head of global fixed income, said this week as he advocated selling into high-yield rallies. “We have probably the riskiest credit market that we have ever had,” Scott Mather, chief investment officer of U.S. core strategies at Pacific Investment Management Co., said last month. Morningstar Inc. just suspended its rating on a fund owned by French bank Natixis SA because of concerns about the “liquidity and appropriateness” of some corporate bond holdings, adding to jitters about a broader liquidity mismatch in the money-management industry.

It’s hard to take this fretting too seriously when central banks persistently come to the rescue. What’s more, in many ways it’s in the best interest of all involved not to get too worked up about those risks.

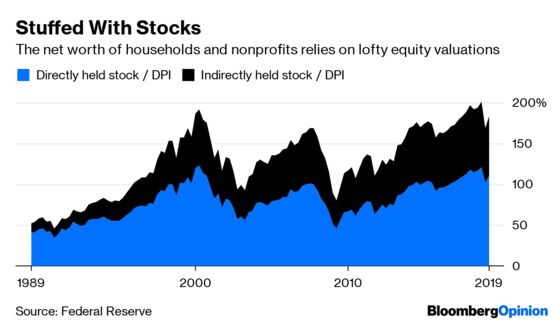

U.S. households and nonprofits had a combined net worth of $109 trillion in the first quarter of 2019, a record, according to Fed data. Dig a bit deeper, and it’s clear that a surge in the value of their equity holdings plays a crucial role. They directly owned $17.5 trillion of stocks, which represents 110% of their disposable personal income. That ratio reached 120% in the third quarter of 2018, very nearly topping the all-time high of 121.2% set just before the dot-com crash. Add in “indirectly held” stocks, and individuals look as exposed to equities as ever. At $12.3 trillion, those holdings were worth 78.6% of DPI in the third quarter, compared with 69.5% at the dot-com peak.

Effectively, the sharp rally in equities has turbocharged a resurgence in the overall wealth of Americans. The prospect of losing those gains is almost too painful to think about. Perhaps that’s why, as DoubleLine Capital’s Jeffrey Gundlach pointed out in January, investors were “panicking into stocks, not out of stocks” during the late-2018 sell-off. “People have been so programmed” to buy the dip, he said, that it reminded him a bit of how the financial crisis developed. Call investors programmed; call them zombies — it’s the same thing.

The Fed, for its part, argues that it’s doing good by sustaining the expansion. Notably, Powell said the economic recovery is starting to reach segments of the U.S. population that had been largely left out thus far — communities that “haven’t had a bull market” and “haven’t had just a booming economy.” Overall, he said officials don’t see signals that the U.S. is at maximum employment. Morgan Stanley’s Sharma argues wage growth is sluggish because bigger companies have more power to suppress worker pay, given that they crowd out (or acquire) startups and other competition.

There are no easy answers to these large-scale problems. That includes central banks simply lowering interest rates or purchasing more government bonds. Powell said as much, noting “we have the tools we have.” But at least he has some room to maneuver toward a soft landing. The ECB, which has pushed yields on some corporate bonds in the region below zero, and the Bank of Japan, which owns large swaths of local exchange-traded funds, have done virtually no tightening and may soon need to ease even further.

The most troubling part of this heavy-handed approach among central banks is that it eliminates the option for investors to earn any sort of return above inflation on safe assets. This delicate balance seems as if it can only last as long as business and consumer sentiment allows. It has been more than a decade since the Fed last cut interest rates, and during that period, it paid handsomely to be a zombie investor throwing money at the S&P 500. With the next easing cycle upon us, much is riding on the status quo prevailing.

Aside from stocks, this includes deposits, direct-benefit promises, non-corporate businesses and other financial assets.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.