Cashed-Up Towns Unable to Spend Threaten Philippine Recovery

Cashed-Up Towns Unable to Spend Threaten Philippine Recovery

(Bloomberg) -- Philippine cities and towns are set to get more money from the central government next year, but many likely won’t be able to spend it, throwing up another obstacle to the economy’s fragile recovery.

Under a 2018 Supreme Court order, local governments will get a bigger portion of national revenue next year, boosting their share in the proposed 2022 budget to more than one-fifth, or some 1.1 trillion pesos ($22 billion). This year they got 18.7% of the budget, or 844.6 billion pesos.

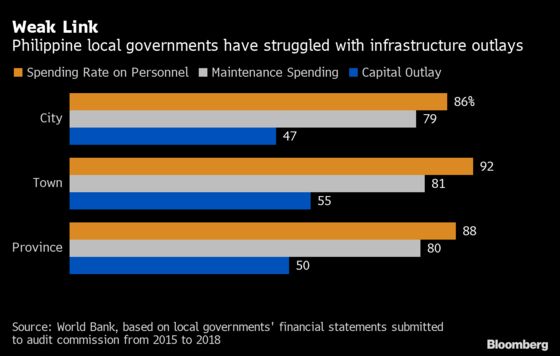

But as much as 155 billion pesos, or 70% of the additional funds earmarked for localities may end up unused, the World Bank estimates. Even now, local governments fail to spend half of the funds they’ve set aside for roads, bridges and other capital outlays due to weak planning, lack of skilled personnel and procurement bottlenecks. And any unspent funds from the tax share would remain in the local accounts, according to the budget department.

Piles of unused public funds are perhaps the last thing the Philippine economy needs. It’s already expected to be among the slowest in Asia to recover from the pandemic, and the country’s economic managers see output returning to its pre-pandemic level only by the end of 2022 or early 2023.

The bigger budget shares comes after the Supreme Court ruled local governments are entitled to a share in all national taxes including customs duties, not just collections by the tax agency. Although the shift aims to improve delivery of basic services, it “could have a negative effect on growth” due to the risk of greater underspending, said Manila-based World Bank economist Kevin Cruz.

‘Atomic Bomb’

Confronted with rising debt, the central government specified duties that local leaders should take on using the bigger revenue share, including critical health care and smaller infrastructure projects like irrigation, roads and school buildings.

Some local leaders are sweating.

“It’s like an atomic bomb will be dropped,” said Carolyn Sy-Reyes, mayor of Pilar, a town of almost 76,000 people that’s 500 kilometers (310 miles) southeast of Manila. Many local governments in places like Pilar lack skilled personnel to spend the bigger budgets and take on additional tasks, she said in a recent online forum.

“The national government devolved as many things as they want to ease its fiscal burden,” said Dakila Cua, governor of the northern province of Quirino and president of a national union of local leaders. Delivery of services may be affected as national agencies aren’t allowed to help fund devolved functions and local governments can’t fulfill them all, he said by phone.

The central government’s budget department, meanwhile, sees the initiative as a “unique opportunity” for local leaders and that the shift is “a milestone in pursuit of the country’s decentralization policy,” it said in an emailed reply to questions.

To address underspending concerns, the national government continues to provide financial management training, the agency said. Disbursement frameworks and minimum performance standards will be in place at local governments next year, it added.

‘Birthing Pains’

The change also risks widening the gap between rich and poor areas. As outlined by law, the new distribution of funds among local leaders will favor densely populated rich cities that have better infrastructure and social services than far-flung towns, said Maria Ela Atienza, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines.

According to the budget department, an equity fund has been set aside for next year to help poorer areas implement their new responsibilities.

Next year’s budget prioritizes social services and education to help address regional inequalities that the pandemic may have exacerbated. Decentralized funding may allow local executives to better promote their constituents’ welfare and mitigate the pandemic’s economic impact, the budget department said.

Despite the central government’s support, there will be “birthing pains” as local leaders, focused on the pandemic response, “struggle to prepare for the shift,” said Nicholas Mapa, economist at ING Groep NV in Manila. “The timing of the switch is precarious given the ongoing pandemic and next year’s elections.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.