California’s Mounting Crises May Be Newsom’s Recall Salvation

California’s Converging Crises May Be Newsom’s Recall Salvation

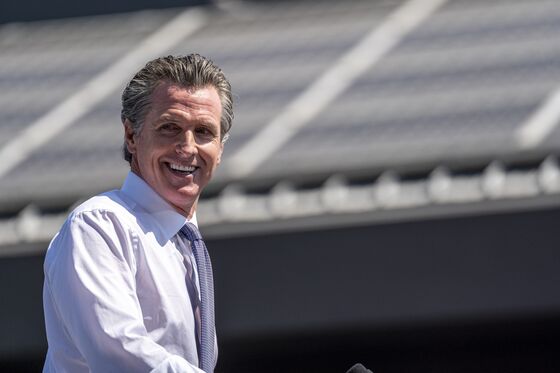

(Bloomberg) -- California enters next week’s historic recall election besieged by crises: massive wildfires, a drought forcing water rationing and a resurgent pandemic filling hospitals.

Oddly enough, they all may help Governor Gavin Newsom keep his job.

Polls show the Democrat prevailing in the Sept. 14 recall, beating back a mostly Republican field of challengers. If Newsom wins, the same crises his opponents used as campaign issues against him likely will have helped cement his victory. Voters beset by calamities may be unwilling to take a chance on his challengers, most of whom have never held elected office.

“The fires, drought, power outages -- all of the bad news in California requires some experience in Sacramento, and that message seems to be resonating,” said David McCuan, chairman of the political science department at Sonoma State University. “It looks like they’ve had a security-blanket effect with voters.”

The prospect of disaster has always loomed over Newsom, who since taking office in 2019 has faced record-setting wildfires, the bankruptcy of the state’s largest utility and an unrelenting pandemic. The election is now happening in a crisis scenario that Democratic leaders had hoped to avoid, and yet it may work in the governor’s favor.

A poll released Friday by the University of California, Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies showed momentum growing. About 60.1% of likely voters said they would reject the recall, according to a poll of about 10,000 registered voters conducted between Aug. 30 and Sept. 6. That’s up from about 50% six weeks ago.

The situation could easily have gone otherwise. Last week, South Lake Tahoe -- a family vacation spot beloved among generations of Californians -- narrowly escaped destruction in the sprawling Caldor Fire, which had already erased several smaller communities in its path. Had the town burned, public anger could have found a ready target in the governor.

“The threat to Newsom has always been that events would spin out of control,” McCuan said.

Just weeks ago, polls showed Newsom, 53, in a tight race to survive in a state where Democrats outnumber Republicans by nearly two to one. National leaders have stepped in to help, with Vice President Kamala Harris stumping for him this week in the San Francisco Bay area and former President Barack Obama recording a video message to bring out voters. President Joe Biden will be campaigning for Newsom next week.

Pandemic Anger

Efforts to recall the first-term governor stretch back to 2019, but the Covid-19 pandemic gave them new fuel. Newsom moved aggressively to shut down the state early in the pandemic, a step polls showed most residents supported.

But some Californians bitterly resented lockdowns -- and started circulating petitions. Recall backers collected more than 1.7 million valid signatures to force an election, comfortably above the nearly 1.5 million required by law.

Democratic state officials picked the election’s unusual timing. Rather than wait for a more traditional November date, they gambled on September. At the time the decision was made in early July, the economy had fully reopened, Covid case rates had plunged, and Newsom’s political standing looked strong. Waiting could give his opponents more time to organize and plunge California deeper into its annual wildfire season.

The gamble didn’t quite pan out. The delta variant caused virus cases to soar. Fires started early and quickly grew huge, with one -- the Dixie Fire -- becoming the first in history to burn all the way across the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

“If the Democrats in the legislature had known that in addition to Covid, the state would be dealing with wildfires, drought and school reopening problems, they might have stuck with November,” said Dan Schnur, a former spokesman for Republican Governor Pete Wilson who now teaches political communication at several California universities.

Newsom’s opponents took the state’s many crises as ready ammunition.

Republican businessman John Cox, who lost to Newsom in the 2018 gubernatorial election, has run television ads listing fires, homelessness and crime as proof of Newsom’s bad management, saying “Gavin, you’ve failed.”

Conservative commentator Larry Elder, who leads the polls among candidates trying to replace Newsom, made a campaign stop at a shrunken reservoir to criticize the governor’s drought response. And he’s pointed to a June report from CapRadio and National Public Radio that found 35 high-priority wildfire prevention projects touted by Newsom only covered 11,399 acres of 90,000 acres they were supposed to treat.

A spokeswoman for the governor said the 35 projects “strategically and collectively protected a total area of 90,000 acres and more than 200 communities.”

Kim Nalder, a political science professor at Sacramento State University and executive director of CalSpeaks Opinion Research, said many people in the mountain areas suffering the worst of the fires do blame Newsom.

“People are very much searching for a target for their anger, for their desperation, really,” she said.

But many of those corners of California already trend Republican. The same applies to the drought-stricken Central Valley. Voters there weren’t likely to vote for Newsom anyway.

“They will add his handling of Covid or the handling of the economy, schools, the drought, fires to the long list of things they don’t like about him,” said Mark Baldassare, chief executive officer of the Public Policy Institute of California.

The institute’s polling shows that while Californians worry about the crises facing them, that concern hasn’t led to big shifts in Newsom’s support, one way or the other.

“If anything, it tends to reinforce what people already feel about him,” Baldassare said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.