Clinics in Davos That Tackled Tuberculosis Now Treat Burnout

Clinics in Davos to Tackle Tuberculosis Now Treat Burnout

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up here to receive the Davos Diary, a special daily newsletter that will run from Jan. 20-24.

The clinics of Davos, built more than a century ago for treating tuberculosis, are now tackling afflictions of the 21st century.

A century after Thomas Mann’s novel about a German who travels to the Swiss resort to visit his ailing cousin, the well-heeled are still trekking to the Alps for treatment, with burnout and depression among the reasons.

While some former sanatoriums like the Schatzalp, thought to be the setting for Mann’s book, now host vacationers and conference attendees, the century-old Hochgebirgsklinik is one of several in the region offering mental health services.

The World Economic Forum, which holds its annual meeting of business leaders and A-list politicians in Davos next week, has called it a “pandemic.” It’s devoting several sessions this year to the issue, including discussions on how to lead a healthy organization and a mindfulness retreat to help participants lower their blood pressure.

There’s certainly a need. While Japan is infamous for punishing long hours, and even has a word, “karoshi,” for death-by-overwork, work strain isn’t confined to Asia.

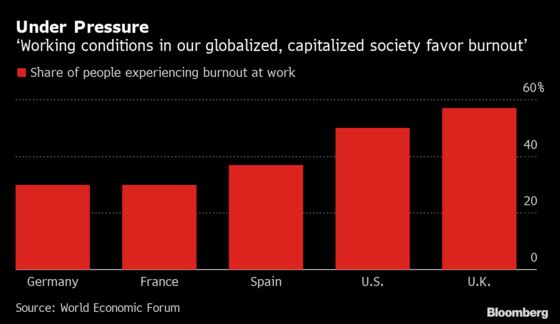

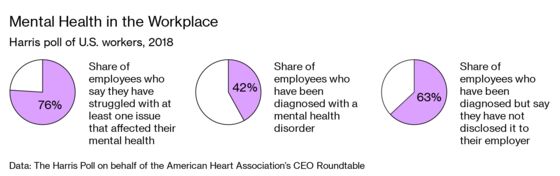

About three quarters of U.S. workers experience job-related burnout, according to a 2019 Gallup study. In Germany, the number of people on sick leave for psychological distress has more than tripled in the past 20 years, while in Britain stress, depression and anxiety constitute nearly half of all work-related ill health cases.

“The working conditions in our globalized, capitalized society favor burnout,” said Michael Pfaff, a psychiatrist at the Clinica Holistica Engiadina not far from Davos. “The numbers are increasing, even though there’s been a lot invested in companies’ health management.”

Beyond the important personal and social effects, there’s a financial consequence in the form of lost productivity, staff turnover and joblessness, which means companies ought to take notice.

The OECD puts the price tag for mental health problems such as depression and anxiety disorders at roughly 4% of GDP. In the European Union, lower productivity and employment rates among people afflicted amounts to a 260 billion-euro hit to the economy. Add to that the cost of greater spending on social security and healthcare.

The term burnout was coined in the 1970s, and at the time considered chiefly an affliction for health-care professionals. Yet in the always-switched-on 21st century, it’s a growing issue.

“If there’s a constant state of pressure, it’s a problem,” said Walter Kistler, an internist at the Davos general hospital, who also runs a walk-in clinic at the WEF. Companies “should learn to be more careful with their resources, including their people.”

According to Kistler, many patients have physical complaints like backaches or insomnia and don’t realize the culprit is stress. It’s therefore difficult to say whether the prevalence of burnout and depression is increasing, or whether they’re just diagnosed more frequently.

There are signs firms are beginning to change. Volkswagen famously switched off some employees’ access to after-hours email, while Microsoft Corp. offers workers 12 free counseling sessions and is building on-site counseling services.

Lloyds Banking Group Plc, whose CEO Antonio Horta-Osorio suffered stress-induced insomnia and took a leave of absence in 2011, offers private insurance that covers mental and physical health issues equally and is training senior managers on how to respond to staffers with a condition.

Yet much like the WEF itself, which gets criticized for just being a talking shop for the global elite to debate issues like inequality and global warming without ever doing anything substantive, companies may only be paying lip service to tackling burnout.

“We are at the beginnings of substantive, real changes,” said Jeffrey Preffer, a professor at Stanford University and author of the book, ‘Dying for a Paycheck.’ “Nonetheless, progress is slow because companies see trade-offs where none exist and all too frequently do not address the root causes of the workplace issues.”

--With assistance from Harumi Ichikura, Stefania Spezzati and Cynthia Koons.

To contact the reporters on this story: Catherine Bosley in Zurich at cbosley1@bloomberg.net;Jana Randow in Frankfurt at jrandow@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.