Harvard Goes Slow, Purdue Buys Plexiglass: Covid Upends Colleges

Bringing Students Back to College Poses Ultimate Test for Many

(Bloomberg) --

Harvard and Princeton universities will limit how many students can return to campus this fall. Colby College will bring everyone back and test them twice a week for Covid-19. At Rutgers University, most classes will be online.

Purdue University said last month it had purchased over a mile of plexiglass, then used the announcement as a fundraising pitch. Georgia’s public institutions, meanwhile, only moved to require masks on Monday.

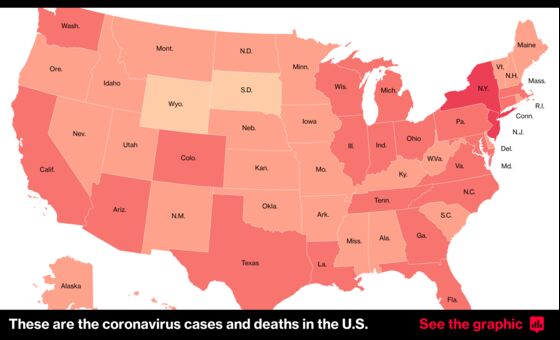

With the start of school fast approaching, colleges and universities across the U.S. are rushing to rejigger the higher-education experience for the coronavirus era. Many are seeking ways to reopen empty dorms and classrooms or shifting to a mix of in-person and virtual classes so they can both safely educate students and protect the schools’ financial health.

Back-to-school season will be tested by a fast-moving pandemic that’s regularly setting records for new cases and has already halted or reversed other reopening plans. Even before classes resume, the consequences are coming into focus: At the University of Washington, an outbreak on Greek Row left at least 142 students with Covid-19.

The University of Texas at Austin said Tuesday that a member of its custodial services team died of the virus -- a reminder that schools have the safety of faculty and staff to worry about as well.

Schools’ range of plans showcases the lack of consensus despite their many shared challenges, including the feasibility of mass screening and the health risks posed by nightlife and athletics. Colleges are also under tremendous financial strain, and the additional costs of testing -- on top of the need to ramp up cleaning and find ways to keep students distanced in classrooms and housing -- adds to their concerns.

Academic leaders are “trying to weigh what’s best, health-wise, versus what will make sense for the economics of the university and the communities in which they’re located,” said Ronald Ehrenberg, an economist who also directs the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute. “And by the way, no one knows what the right thing is to do.”

While a debate rages over the Trump administration’s guidance this week on returning elementary, middle and high-school students to empty classrooms, colleges have been left to their own devices.

Read More:

Some institutions have decided that reopening campuses will require testing on a mass scale, despite the cost and logistical hurdles. Even that isn’t a panacea, though: It will have to be paired with measures like masks, social distancing, hand-washing and contact tracing, scientists warn.

At Princeton, “testing and masking are essential pieces of that,” President Christopher Eisgruber said in an interview this week. The school is requiring everyone to cover their faces when indoors, except if they’re alone or in their living quarters, as well as testing all students regularly. Parties are banned.

If the school can “test regularly enough and accurately enough and quickly enough to know with a high degree of confidence what level of infection we have on the campus, that can help us get back to normal,” Eisgruber said.

For Colby, a small liberal arts college in Maine with a student body of about 2,000, its goal of testing each person twice a week will require about 85,000 tests in the fall semester.

The University of California San Diego, on the other hand, has a campus population of about 65,000. It’s looking to test at least 75% of anyone returning to campus every month, said Natasha Martin, an associate professor in the school’s division of infectious diseases and global public health. Should they be able to bring everyone back, that could mean more than 1,600 individuals each day.

“We are using testing to be able to detect outbreaks early,” Martin said. But “testing the population every month is not sufficient to curtail an outbreak, only to tell you that you have a problem before too many people are infected.”

Colleges and universities will find no guidance on universal testing from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which doesn’t recommend it and calls the benefits “unknown” in curbing transmission. Only if a school is in an area with significant community transmission does the CDC say officials should weigh testing asymptomatic people.

Carl Bergstrom, a professor of biology at the University of Washington, called the CDC position “absolutely baffling” since “everybody is using this” as a method to identify people who could spread the virus.

“It’s a nuisance, and maybe kind of expensive, but it’s existential if you’re going to have a fall semester. It’s better than closing your doors,” Bergstrom said. “It’s a big ask, but it’s not an impossible ask.”

In a research preprint put out on Tuesday that hasn’t been peer-reviewed, Yale and Harvard researchers proposed a model for screening college students every one to seven days. Frequent testing on rapid-result devices paired with quarantining positive patients can help control outbreaks at a reasonable cost, they said.

Individual actions will also be key given “the fragility of the situation and the ease with which inattention to behavior may propagate infections and precipitate the need once again to shut down campus,” the authors said.

Pooled Testing?

Testing isn’t cheap, though, and high demand has seen wait-times for results top one week. Commercial diagnostics start at about $100 apiece. Some schools have their own labs to process the tests, which can cut the price and speed results. The Yale and Harvard analysis assumed tests would cost from $10 to $50.

In upstate New York, modeling done for Cornell University by faculty and graduate students proposes “aggressive” screenings of students, faculty and staff every five days and relies on the school’s animal health diagnostic center and group testing to lower costs. Testing just once a week would lead to a “41% increase in infections and hospitalizations,” according to the Cornell paper.

So-called “pooled” testing has been much-heralded for use on campuses but is still experimental and will require the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval. Labs at several schools are working on them, and at least one has submitted for FDA clearance.

‘All These Rules’

If these strategies work, they could set a example for the rest of the country, where testing and contact tracing remains under-developed.

“Colleges and universities have an opportunity right now -- and time will tell if they’re able to seize that opportunity and run with it and demonstrate leadership -- for how safe reopening can be done,” said Jennifer Doudna, a pioneering researcher at the University of California, Berkeley who discovered the gene-editing tool CRISPR. Earlier this year, Doudna converted a genomics lab she leads called the Innovative Genomics Institute to do Covid-19 testing and is working with the UC campus to provide screenings.

But higher education institutions also bear a particular risk of super-spreading events at parties and other large-scale social situations, something they have sought to address with policies for student behavior. Enforcement remains unclear.

Places where there’s “shouting and no masks, those I worry a lot more than 20 students sitting in a seminar room talking about quantum physics,” said Chip Schooley, a virologist at UCSD who has also been leading the school’s “Return to Learn” plan.

Benjy Renton is a student at Middlebury College. His plans to study abroad in Beijing were short-circuited by the virus. After he returned to Middlebury’s campus in Vermont, that too was shut down.

The 20-year-old is now living at home in New York, and the experience sparked an interest in how the virus is affecting higher education. He’s been tracking reopening plans for his China-focused blog, “Off the Silk Road.”

“The biggest wild card is obviously student behavior,” he said. “I do hope students like myself are going to abide by all these rules. But I think I know that’s just not going to happen.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.