Bond Vigilantes Won’t Corral Stampeding Budget Deficits

Bond Vigilantes Won’t Corral Stampeding Budget Deficits

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s a growing school of thought that federal budget deficits in the U.S. don’t matter. Just last week, Stony Brook University’s Stephanie Kelton and my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Noah Smith debated that very question: When — if ever — should we start worrying about the growing national debt?

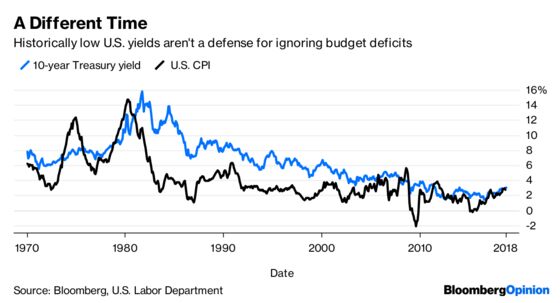

Building upon that idea, Bloomberg News reported recently that the consensus among Washington politicians is that trillion-dollar deficits are considered “whatever” now that Republicans have moved away from the Tea Party movement and embraced the Trump administration’s fiscal freewheeling. Supporting this general ambivalence, the writers and others have said, is the fact that bond traders aren’t sending Treasury yields through the roof in anticipation of widespread inflation.

That way of thinking is outdated. It goes back to the notion of “bond vigilantes,” a term coined in the 1980s to describe how debt markets could could punish governments for economically irresponsible policies. That kind of power is long gone. The game has changed. If it’s still historically cheap for the U.S. to borrow money, therefore proving that deficits don’t matter, what about Germany, where 10-year bunds yield 0.47 percent, or Japan, where the 10-year yield is just 0.13 percent?

The answer, of course, comes down to the post-financial crisis role of central banks. While the Federal Reserve is gradually reducing its balance sheet, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan are still very much juicing their economies. As I’ve written before, the idea of a “great unwind” of their extraordinary monetary stimulus is unlikely to come to fruition. By the time the main central banks are ready to tighten in unison, the world will probably need them to ease once again.

This is why the old way of thinking about yields and deficits no longer applies. Just because they’re low by historical standards doesn’t mean there’s no fear in the market about America’s national debt. In fact, it may seem paradoxical, but some investors argue that lower yields are a logical byproduct of years of rampant spending. Massive government borrowing pulls forward economic growth and causes interest payments to make up a growing share of the federal budget. If interest rates reached double digits, as they did in the 1980s, it would only exacerbate the situation.

One investor who remembers those days is Dan Fuss at Loomis Sayles & Co. Just a day after his 85th birthday, he told me about an “old memory I’ll never forget.” In 1981, the U.S. Treasury was offering debt with a 15.75 percent interest rate, and it was clear Wall Street was reluctant to buy it. The benchmark 10-year yield had soared from 9.5 percent in mid-1980 to almost 16 percent by the time of the sale. The feeling, Fuss said, was that rates could go even higher.

Of course, it turned out to be the peak in U.S. yields. Fuss says that Treasury bond was possibly the single-best investment he’s ever made at Loomis. The lesson, he says, is that even in the most trying times, investors will finance America. “The U.S. has the strongest currency in the world,” he said.

But here’s the rub. “At what point — and I don’t know how to measure this — do you lose confidence in the currency?” Fuss asked. The dollar is the reserve currency of the world, and that doesn’t seem to be changing soon. But he shares the same concerns as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Robert Burgess about whether America’s pullback from the global stage will threaten King Dollar.

One of the key pillars of Modern Monetary Theory (championed by Kelton, among others) is that deficits are irrelevant when a sovereign nation can create as much money as needed to pay what it owes. This is an alluring premise, but it only works when you are a global superpower, or at least close to it. It’s why the U.S. and Japan can run up their debt without sweating, but Turkey and Argentina can’t without bouts of intense inflation. It’s why the prospect of a 2.4 percent budget deficit is roiling markets in Italy, with 10-year yields rising the most since May.

There will come a point, too, when markets sound the alarm on the U.S. national debt. The Treasury market is now $15.3 trillion in size, compared with $4.9 trillion a decade ago. According to data from the Institute of International Finance, U.S. federal debt as a whole makes up more than 100 percent of gross domestic product.

That day of reckoning is not coming soon. But if it ever does, I doubt yields will give anyone much of a heads-up. Too many factors are keeping them down, from an aging population demanding safe assets to slower productivity hampering economic growth. At least for now, the world has little choice but to keep America’s debt machine churning.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.