Brazil Development Bank Missing in Action as Crisis Bites

Big State Spender Stingy on Stimulus When Brazil Needs It Most

(Bloomberg) -- Brazilian businesses, desperate for government aid to weather the pandemic, aren’t getting much help from a state lender that used to shell out more than the World Bank.

In past crises, state development bank BNDES would have been quick to flood the market, swelling its loan books by 30% a year to keep the economy afloat. Now, the bank’s top executive -- tasked with dramatically scaling back the state’s role -- has to navigate a world where governments are suddenly turning on the fiscal taps like never before. That tug-of-war between BNDES’s past and its recent U-turn toward neoliberalism has seemingly left it paralyzed, said one former executive.

“This is a black swan event like one I’ve never seen,” said Luiz Carlos Mendonca de Barros, an economist and former BNDES president in the 1990s. For the bank’s new management, “stimulus is the devil.”

When Gustavo Montezano took over as BNDES’s chief executive officer in July after a 17-year career in financial markets, he laid out an ambitious plan to overhaul the bloated government lender. Top of his list of priorities: stop flooding the economy with cheap loans, sell off multi-billion-dollar stakes in Brazil’s biggest companies, and start acting more like a traditional investment bank.

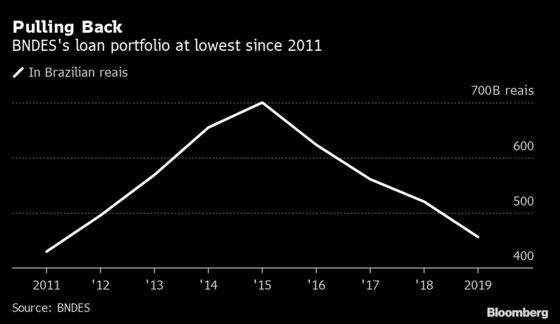

It was a lofty goal applauded by markets -- for years investors had complained BNDES’s subsidized rates undercut monetary policy, boosted public debt and gave unfair advantage to handpicked companies. Last year, BNDES slashed lending to the least since 1996, a stark contrast to its $165 billion loan book from just a few years earlier.

Then came the coronavirus.

Just part-way through a divestiture spree in which BNDES sought to raise billions, global markets collapsed, with the Brazilian real and the nation’s Ibovespa index among the hardest hit. Suddenly, the bank was receiving calls for emergency assistance, with airlines like Gol Linhas Aereas Inteligentes SA among the first to enter talks.

The institution could easily come up with 100 billion reais (about $20 billion) in direct funding to shore up vulnerable companies, said Mendonca de Barros, but it’s been painfully slow out of the gate. Such a move goes against the free-market fundamentalism at the bank and throughout Jair Bolsonaro’s economic team, he said.

So far, BNDES has announced 97 billion reais in aid, but only 7 billion reais of that is in new loans, which need to be approved and distributed by private banks. The rest is delayed interest payments for existing loans, a transfer into an employee savings account, and the distribution of government assistance for companies to pay wages. Montezano said March 29 that BNDES will also support companies’ cash flow through the purchase of local five-year bonds that are convertible to stocks and carry below-market interest rates.

The announcements so far have underwhelmed markets and economists -- and even the bank’s own workers.

“BNDES is the main tool of the government for countercyclical action,” Arthur Koblitz, president of BNDES’s employee association, wrote in an April 4 column in Folha de S.Paulo newspaper. He accused management of “deliberately” sitting on the sidelines.

BNDES didn’t respond to an email seeking comment for this story.

The big piece most market watchers are waiting for is help for Brazil’s battered airlines. Gol CEO Paulo Kakinoff told analysts on a Tuesday conference that talks with BNDES are evolving well, although he said a proposal could take 30 days or longer.

Governments around the world have committed trillions of dollars to combat the fallout from the coronavirus as shops, offices and airlines halt most operations. Not surprisingly, the push is being led by developed economies, which Bloomberg Economics says so far seems sufficient to support a second-half recovery. In emerging markets, however, where funds are in short supply, stimulus looks set to fall far short.

It’s a situation playing out across the once-spendthrift Latin America. Mexico’s Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador said last month there will be “no more rescue plans to banks and big businesses like they did in neo-liberal times.”

In Brazil, the barriers to broader BNDES involvement are twofold. After a crippling recession and a sluggish rebound, Brazil doesn’t have the fiscal might and flexibility to shock and awe like Germany or the U.S. And even if it did, Bolsonaro’s economic team is ideologically opposed to the big-spending policies that were cornerstones of former governments.

To avert a costly stimulus package under discussion in Congress, Brazil’s Economy Ministry is proposing to transfer 30 billion reais to states and municipalities to ease the impact from the virus, said two people familiar with the matter, asking not to be identified because the discussion is not public.

It’s a stark contrast from a decade ago, when Brazil leaned heavily on state banks to buffet the economy after the global financial crisis. BNDES’s loan portfolio swelled 31% in 2009 and another 27% in 2010, and kept on expanding to peak at about 700 billion reais at the end of 2015. But that credit explosion was part of free spending policies that eventually stoked inflation and widened deficits to unsustainable levels, leading Brazil to lose its investment grade rating.

“In past crises under other governments, public banks increased lending, even to small and medium sized companies and the retail industry,” said Claudio Gallina, a senior director for financial institutions at Fitch Ratings. In the end, they “had to restructure because of capital issues.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.