Biden’s State Rescue Dwarfs Tax Hit, Turning It Into Stimulus

Biden’s State Rescue Dwarfs Tax Hit, Turning It Into Stimulus

(Bloomberg) -- Listen to any of the architects of the $1.9 trillion spending package winding its way through Congress -- from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to White House economic adviser Brian Deese -- and they will tell you the aid is urgently needed to rescue the economy.

It is, they insist, simply relief for Americans struggling to get through the pandemic.

But at least one important slice of the package -- the nearly $200 billion being earmarked to state governments -- goes beyond a rescue and is almost certain to further stimulate an economy that is already beginning to rapidly recover.

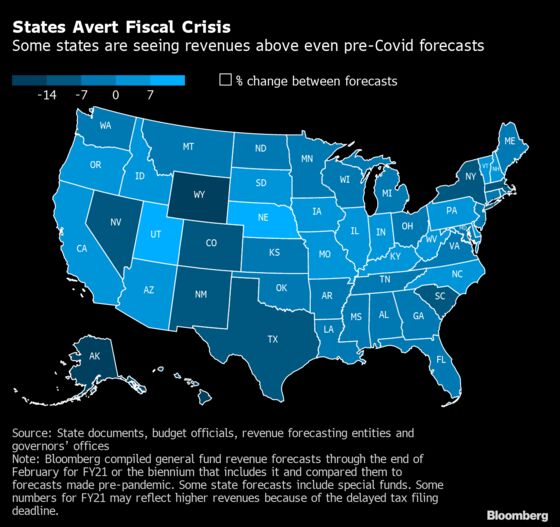

That’s because those proposed cash transfers are more than six times greater than the approximately $31 billion of expected tax revenue that disappeared in the current fiscal year, according to pre-pandemic and more recent forecasts compiled by Bloomberg. In other words, that money could make up for that loss and be plowed back into states’ economies, such as their own version of relief checks, infrastructure projects and more, depending on the federal guidelines around the aid.

That would give states an improbable role in spurring the recovery and end the steady budget cutting that has weighed on the economy since March and already eliminated more than 1.3 million state and local government jobs, nearly twice as many as were lost after the last recession. Yet it has also set off a debate in Washington over whether some of the money should be cut or shifted to other priorities that could provide a more immediate impact than funneling it through sometimes slow-moving state governments. Local governments would get another $130.2 billion under the bill that has already passed the House.

“If the whole point of this bill is to stimulate economic activity, the federal government has ways of doing that, that may be more efficient than sending checks to state and local governments,” said Dan White, the director of public sector research at Moody’s Analytics, which estimates that states would need a total of $56 billion to cover shortfalls through 2022 once previously allocated aid is taken into account.

Based on state revenue projections made before the pandemic and more recent ones revised through the end of February, revenue is expected to be down by a weighted average of about 3% in 2021 compared with expectations before the pandemic, according to an analysis by Bloomberg. The numbers include forecasts from all 50 states made by budget officials, revenue forecasting entities and governors’ offices.

The forecasts cover fiscal year 2021 -- which ends in June for almost all states -- or the biennium that includes it. The figures include states’ general funds as well as special funds in cases where they receive a significant amount of specific tax collections, such as Michigan’s School Aid Fund.

Fiscal Hit

The revenue tallies are just one way to gauge the impact that the virus has had on states and doesn’t account for the jump in costs during the public health crisis. In some cases, the toll may be understated because tax deadlines were shifted into July. In Illinois, for example, that change inflated this year’s revenue collections by about $1.3 billion, according to Carol Knowles, a spokesperson for the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget.

Moreover, the fiscal hit could continue into next year, depending how final tax collections shape up, and states face additional costs associated with the pandemic. States have also borrowed more than $50 billion from the federal government to cover a deluge of jobless claims.

Cities and counties have also been calling for aid throughout the pandemic, and their lobbying groups have been supportive of the Biden administration’s $350 billion total lifeline to states and municipal governments. Metropolitan areas like New York City have been upended by Covid-19, which devastated its tourism and hospitality industries. The rise of remote work has also raised longer-term concerns about a shift away from urban centers. The city’s Independent Budget Office said in a report that it lowered its forecast of tax revenue in 2021 by $4.4 billion versus its projection in January 2020.

Uneven Impact

Even so, by all accounts the financial impact overall has been far smaller than initially feared when Covid last year sent the U.S. economy into the deepest recession since World War II, which left governors nationwide bracing for the gravest fiscal crisis of modern times. In April, the National Governors Association called for Congress to provide $500 billion to cover expected budget shortfalls.

Deficits on that scale were averted after the federal government pushed through stimulus plans in March and again late last year, driving stocks to record highs and promising to increase collections of capital gains taxes. The magnitude of the shortfalls also reflects the unusually uneven nature of the recession: While lower paid service industry employees were thrown out of work, the highest earners who pay far more in state taxes were less affected because they were able to work from home.

The result has been in some cases dramatic. California, a state that’s heavily dependent on income-tax revenue from the highest earners, is seeing revenue collections run about 10% more than was anticipated in the budget for the fiscal year that will end in June. In Oregon, the pandemic-era revenue losses “pale in comparison” with those of previous recessions, forecasters wrote in a Feb. 24 dated report.

Others haven’t been so lucky. Hawaii’s tourism-driven revenue base nearly evaporated, causing its revenue forecast to drop about 19% from pre-pandemic expectations for fiscal 2021, data compiled by Bloomberg show. In New York, the initial epicenter of the virus, general-fund revenue is estimated to be 11.7% below pre-pandemic forecasts. Yet even in that case the situation has improved: Governor Andrew Cuomo on Tuesday announced an agreement with both houses of the legislature to recognize $2.5 billion in additional revenue over two years, part of the budget-making process in the state.

Aid Debate

The scope of the federal aid needed to help states and local governments with their budget shortfalls has been a sticking point in Congressional negotiations for months. Former President Donald Trump had repeatedly called it a “bailout” for poorly run states -- an argument echoed by other Republicans even though the effects are being felt across party lines and are the results of diminished revenue, not profligate spending. Republican Senator Mitt Romney called the scale of President Joe Biden’s proposal “wasteful and harmful.” Moderate Democrats in the chamber are looking at state and local aid as they try to make the proposal more targeted.

The government “should be cautious about overdoing it,” Jamie Dimon, chief executive officer of JPMorgan Chase & Co. said in an interview on Bloomberg Television this week. His bank has been tracking state tax revenue and found many are still seeing increases. “Get us through the problem, get the country growing, but try not to overdo it too much.”

The states are hindering the recovery, though. Moving rapidly to cut spending after the virus struck in anticipation revenue would disappear, states and local governments exerted a drag on the economy from April through December, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. They’ve also been slow to hire back workers who were laid off, signaling uncertainty about the outlook.

“The more it drags, the harder it becomes for state and local governments to come out of this crisis,” said Lucy Dadayan, senior research associate with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “When the federal aid is sidelined, it changes the economic recovery.”

‘Upside Surprise’

The legislation approved by the House sets aside $195.3 billion for states and Washington, D.C., with each state receiving at least $500 million and using the amount of unemployed residents as a factor in determining the allocations, according to the legislation.

If left unchanged, states would be able to use those funds to address “negative economic impacts,” and cover pandemic-related costs or make up for revenue that fell below projections made by January 2020.

Overall, state revenue has been little changed by the pandemic. In the year ended in December they fell by an average of 0.12%, according to data on 47 states tracked by JPMorgan. A little more than half of states tracked by the bank saw a year-over-year decline in taxes, while 21 saw positive growth year-over-year.

Peter DeGroot, a municipal strategist for JPMorgan, said the revenue figures show a “sizable upside surprise.” But he noted that there are many other factors affecting state finances, such as higher costs from fighting the pandemic and distributing the vaccine.

“It’s not simply a revenue story,” he said.

Funds Welcomed

Before the pandemic, Louisiana was seeing a turnaround in its finances after struggling for years to recoup from the last recession.

Jay Dardenne, the state’s commissioner of administration, said that he would welcome any money that Congress provides and a clear objective would be to use the funds to help Louisianans hurt by the pandemic.

“I think it can help states continue the transition from the problems experienced during the last year to what is hopefully brisk economic recovery,” he said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.