Biden’s Competition Order Seen Fueling Long-Run Gains for Economy

Biden’s Competition Order Seen Fueling Long-Run Gains for Economy

(Bloomberg) -- President Joe Biden’s new plan to promote competition across industries and in the labor market can deliver long-run gains for the U.S. economy by boosting productivity and wages, economists say.

The president announced an executive order on Friday that directs federal agencies to ban or limit non-compete agreements -- which make it harder for workers to switch jobs in search of higher pay -- along with a raft of proposals aimed at barring unfair competition between large and small businesses.

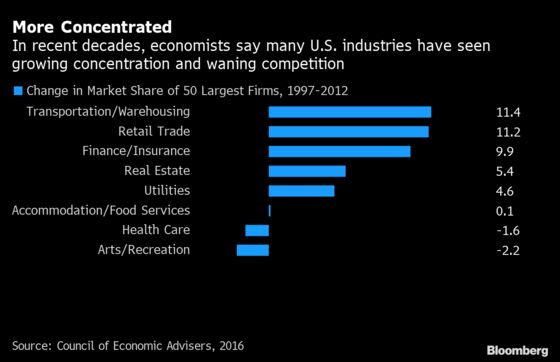

While there’s a focus on the technology, agriculture, transportation and drug industries, some of the measures will apply across the economy. The aim is to counter a trend that’s seen market share in many industries become concentrated in a small number of businesses, widening gaps in income and wealth, the administration says.

“If it’s successful, that’s going to create more competition, improve mobility in the labor market, and in the longer run we could see maybe some upside risk to our forecasts for wage growth and productivity,” said Ryan Sweet, head of monetary policy research at Moody’s Analytics.

Waning competition and the dominance of large firms has been a hot topic for economists in recent years. A series of studies have found that in most U.S. industries there is more concentration now than there was a few decades ago.

Many researchers have argued that this is one reason why wage increases have been slow: with markets for goods or services divided up among a smaller number of competitors, workers in those industries end up with less bargaining power.

‘Flawed Belief’

Reducing the trend toward corporate consolidation will promote competition and provide benefits for workers, consumers, farmers and small businesses, the White House said in a statement outlining the executive order. The measure also aims to step up enforcement of antitrust laws.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the biggest business group, called the idea that the economy has become too concentrated a “flawed belief,” and warned the administration against neglecting the importance of large firms for economic growth.

“In many industries, size and scale are important not only to compete, but also to justify massive levels of investment,” the group said in a statement Friday. “Larger businesses are also strong partners that rely on and facilitate the growth of smaller businesses.”

The move to ban non-compete agreements -- contractual clauses in which workers agree that if they quit or are fired, they can’t leave to work for a competitor, at least for a time -- could remove a barrier to better pay in many industries.

The clauses are meant to prevent trade secrets from being exchanged. Instead, they often end up locking workers into bad jobs and reducing their bargaining power, said Karla Walter, director of employment policy at the Center for American Progress.

What’s a ‘Competitor’?

In 2014, for example, it was revealed that sandwich chain Jimmy John’s was requiring workers to sign non-compete agreements that banned them from working at one of the sandwich chain’s competitors for a period of two years following employment there. The company’s definition of a “competitor” was wide-ranging, encompassing any business that was near a Jimmy John’s location or derived 10% of its revenue from sandwiches.

Walter said that by barring non-compete agreements -- which an estimated one-third of Americans have signed -- worker mobility would increase and entrepreneurs would find it easier to attract talent.

It’s “an important change that will give workers more leverage for higher wages,” said David Jaeger, a labor economist at the University of St. Andrews. “Stockholders in large corporations may feel a pinch in the short run, but the increased competition will likely spur overall growth over the longer term.”

The executive order also calls on regulators to take steps to lower drug prices, toughen merger enforcement in technology and banking, and ensure transparency in airline and shipping fees.

The breadth of the order makes its economic impact hard to gauge, said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the right-leaning American Action Forum. He said the enforcement of non-compete agreements is something that often happens at the state level.

Biden’s order directs more than a dozen federal agencies to begin 72 initiatives to strengthen competition, including with new regulations.

“Will every one of the 72 fully pan out? Probably not. Will the majority of them? My guess is yes, and that’ll add up to a big difference,” Jason Furman, a White House economist during the Obama administration who’s now at Harvard University, said on Bloomberg TV Friday.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.