As Carbon Recedes Due to Virus, Methane Will Likely Increase

As Carbon Recedes Due to Virus, Methane Will Likely Increase

(Bloomberg) -- The travel restrictions and economic unraveling triggered by the coronavirus have led to an unprecedented drop in carbon emissions worldwide. That may feel like a rare bit of silver lining—and yet climate advocates aren’t celebrating. Many are worried about an uptick in emissions of the lesser-known greenhouse gas: methane.

“Unlike carbon emissions, methane emissions don’t decrease when the world’s economy slows down,” says Poppy Kalesi, policy director for European oil and gas at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund. “With lower oil and gas prices, we already see efficiency savings in companies, which means that they might be more relaxed about their environmental protocols.”

Atmospheric methane constitutes the second largest source of global warming after carbon dioxide. Much of that is released in the course of oil and gas production, and much of that, in turn, comes from leaks. Methane is colorless and odorless, and with millions of miles of pipeline in the U.S. alone, leaks are difficult to predict, let alone detect. Just one leak from a fracking rig in Ohio in 2018 released about 120 metric tons of methane an hour for 20 days before its operator, a subsidiary of Exxon Mobil Corp., could stop it, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last year.

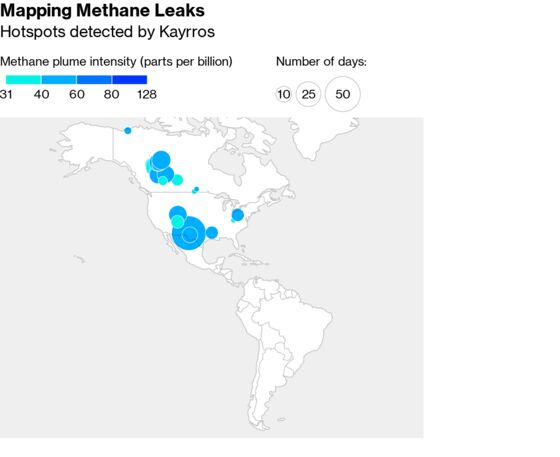

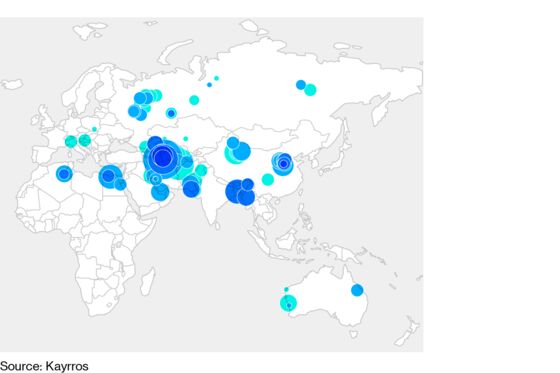

Large global methane leaks from the fossil fuels industry in 2019 were equal to the total volume of CO₂ emitted by Germany and France combined, according to data from Kayrros SAS, a Paris-based technology company. That’s unlikely to improve in 2020.

Two years ago, Kayrros formed a partnership with the European Space Agency aimed at analyzing satellite data to detect, quantify, and attribute methane leaks, a product they finalized in March. “The fact is that there are many more leakages than everybody thought,” says Antonie Rostand, Kayrros’s chief executive officer. And a greater volume, as well: its technology is able to detect only leaks of more than 10 tons per hour. That means far more methane probably leaks each year than Kayrros knows about.

Prior to Kayrros’s technology, quantifying methane leaks largely depended on ground-level sensors, which meant that a leak had to have been detected and precisely located before it could be measured and stopped. “With CO₂, we know upfront where we expect to see emissions,” says Stefan Schwietzke, a scientist with EDF. “But you can’t predict a methane leakage.”

The likelihood of increased methane emissions this year due to the economic downturn isn’t merely hypothetical. Europe’s biggest offshore gas field, Equinor’s Troll A off the course of Norway, canceled multiple maintenance programs after an employee on the rig tested positive for Covid-19. In the U.S., Equitrans Midstream Corp. is rescheduling maintenance activities that aren’t compliance-related as the coronavirus strangles equipment supply lines and threatens worker safety.

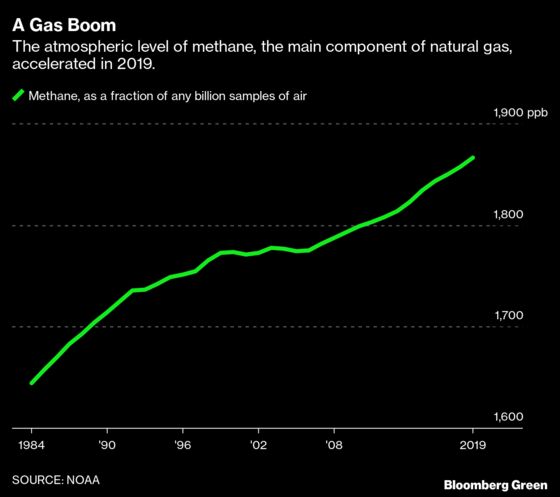

Unlike carbon emissions, which face any number of regulations and limits from governments and corporate sustainability targets, methane emissions have gone largely unchecked. Although it has a much shorter lifespan than carbon dioxide, methane absorbs 28 times as much heat over a 100-year timeframe, making it a much more potent greenhouse gas. Atmospheric methane is more than two-and-a-half times today what it was in the pre-industrial period. “Calculating how much methane there is in the atmosphere is an old technology,” Schwietzke adds. “Understanding where it comes from is the new thing.”

Kayrros estimates that at any given time, there are about 100 high-volume methane leaks around the world. The good news is that once identified, a methane leak is relatively easy to stop. The International Energy Agency estimates that about 75% of current worldwide methane emissions could be avoided—about 40% of that at no net cost. Leaks cost the industry about $30 billion a year in lost revenue, so there are strong incentives for gas companies to detect them early.

The data company has also been involved in discussions with the European Commission on a strategic plan aimed at “leak detection and repair,” focusing in particular on identifying “superemitters” and “hotspots.” This would become the first regulatory framework to control methane emissions, says EDF’s Poppy Kalesi. “It might change the way we see the natural gas industry.”

Luckily, just reducing methane emissions by 40% would have an effect in global warming equivalent to the immediate shutdown of 60% of the world’s coal-fired power plants, according to the IEA. “Reducing CO₂ emissions is important for reducing the magnitude of climate change. Reducing methane emissions is important to reduce the rate of climate change,” says Schwietzke. “It is a way of buying us time. We need both.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.