(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Selling $1,000 iPhones and $2 boxes of Chicken McNuggets may not appear to have much in common. But in fact, Apple Inc. and restaurant chains such as McDonald’s are stuck in a similar dynamic right now: Their healthy sales figures are masking a potentially troubling demand problem.

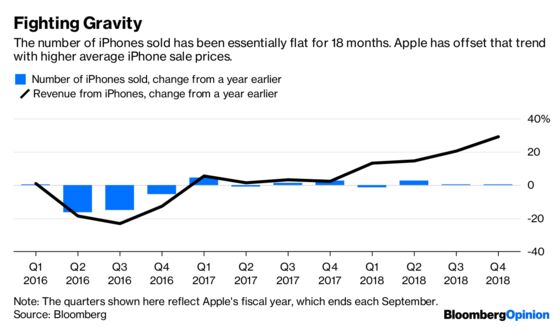

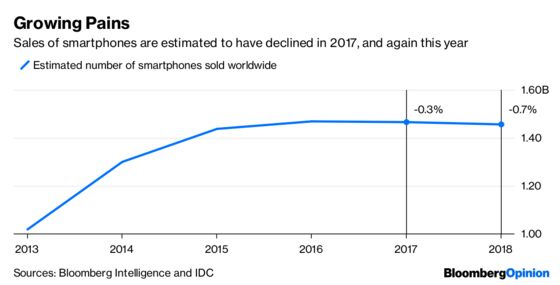

Apple this month said it would stop disclosing how many iPhones it sells every quarter — a move that seemed designed to obscure future declines. In its fiscal year ended in September, Apple barely sold more iPhones than it did the prior year, and the global smartphone market is stalled or declining slightly.

The tech giant so far has managed to offset that industry trend by charging higher prices for its smartphones. The company sold 0.45 percent more iPhones this year than last, but revenue from those smartphone purchases rose 18 percent. That's the power of price increases in a stagnant market.

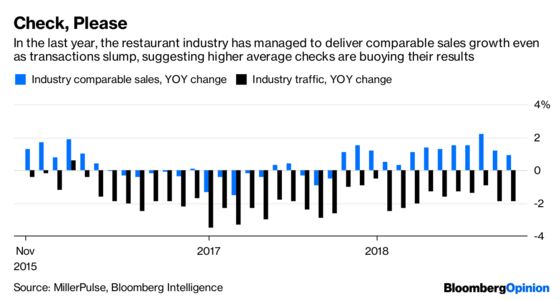

You can see parallels in the restaurant business. The industry overall has seen growth in comparable sales in the last year or so. But that has come in spite of declines in traffic. That means, in effect, that higher average checks are offsetting disappearing diners.

Big names in dining have seen this dichotomy to varying degrees. Starbucks Corp., in particular, has been stuck in a traffic rut for a long time in the U.S., as it struggles to bring in diners in the afternoon hours. McDonald’s Corp. has seen a retreat in U.S. guest counts in each of the last three quarters after seeing growth on this measure in fiscal 2017. Its annual report basically acknowledges that this is far from ideal, stating that when it comes to generating comparable sales growth, "The goal is to achieve a relatively balanced contribution from both guest counts and average check."

Higher average checks don’t necessarily mean a restaurant has hiked prices — though we know that some chains, like Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc., have done just that. It also could mean customers bought more items per order, or that they traded up to pricier meats or other fancier ingredients. But either way, just as at Apple, those fat receipts allow investors to look past the fact that these businesses are struggling to add customers.

Perhaps investors shouldn’t be so forgiving, though, because this is an unsustainable dynamic for any consumer company. In some cases, businesses must charge higher prices to offset rising labor costs, or climbing bills for iPhone parts. But shoppers simply don’t have endless capacity to keep paying more for their favorite stuff. This is especially true with cracks emerging in the global economy.

In the case of both Apple and many restaurant chains, the reason for the difficulty in attracting more customers is similar, and it’s one that’s hard to combat: Saturation.

For Apple, the smartphone industry has simply run out of growth, at least for now. In many countries where smartphones have become standard consumer purchases, the likeliest buyers now own at least one of the devices, and people are holding onto their phones for longer. In the U.S., people on average go more than three years between smartphone purchases, up from about two years in 2014, according to mobile industry consultant Chetan Sharma. Those trends make it tough for any smartphone maker, including Apple, to boost the number of phones it sells every year.

And the restaurant industry, much like its mall-retailing peers, has blanketed the U.S. with more locations than the market can support.

Against this backdrop, both businesses need to think much more imaginatively about ways to drum up customers. Many restaurants need to be quicker about embracing delivery in order to help them attract diners who would previously have gone to a grocery or convenience store. More should consider Starbucks-like loyalty programs that give patrons a reason not to spread their business around among different chains. Jennifer Bartashus, a Bloomberg Intelligence analyst, says that value-conscious fast-food customers tend to be the least loyal. So perhaps restaurants could do a better job of giving them incentive to visit more often.

Apple doesn’t talk about waning demand for smartphones, but it is deploying tactics to offset the trend. For example, it’s offering more add-on products such as the HomePod speaker, Apple Watch and Apple Music for streaming audio. The company could do much more. Only about 5 percent of people with iPhones or iPads pay for Apple Music, and just 13 percent of iPhone users opt for Apple's repair warranty service, according to Morgan Stanley estimates. The company could market those products more aggressively, and it could sell some of its products and digital services together, like offering Apple Music subscriptions to buyers of the HomePod for a slightly reduced price.

These potential tactics may not pack the same punch for restaurants and Apple as an entirely new concept or product line, but they are also a pragmatic response to meek demand. After all, the world only needs so many iPhones and Pumpkin Spice Lattes.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Sarah Halzack is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She was previously a national retail reporter for the Washington Post.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.