An $8 Trillion Spree Sets Clock Ticking for Bonds’ Judgment Day

An $8 Trillion Spree Sets Clock Ticking for Bonds’ Judgment Day

(Bloomberg) -- Global bond buyers may only have a year until the good times run out.

A multi-trillion dollar wave of government debt sales has -- so far -- found seemingly endless support as nations around the world raise cash to fight the economic hit of the coronavirus. The U.S. sold a record amount of debt at auctions this week, a German long-dated offering drew the strongest demand since 2012, and the U.K.’s first-ever syndicated 10-year sale received seven times as many bids as needed. Meanwhile, Australia raised the equivalent of $12 billion in its biggest-ever offering.

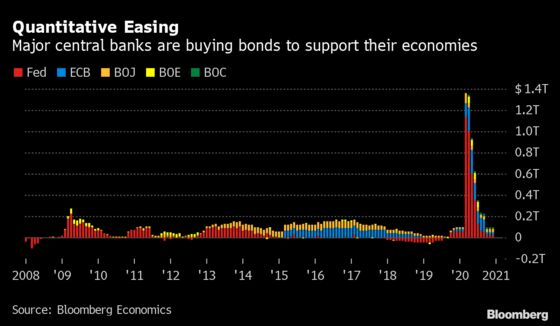

The milestones share a common theme: Investors are mopping up the sales as long as central banks engage in so-called quantitative easing, buying an unlimited amount of debt to counter the ravages of the pandemic. But at the first whiff of a recovery, or a pullback from policy makers, all bets may be off. Throw in the threat of inflation amid a global fiscal splurge exceeding $8 trillion, and bond investors look set for a toxic cocktail of risks in the not-too-distant future.

“Given the massive central bank easing, which includes a lot of bond-buying QE in many places, there will be a lot of demand right now to buy government bonds,” said Eric Stein, co-director of global income at Eaton Vance Management. “However, if it was a year or two from now and the economy was picking up and inflation had started to pick up, the story could be different.”

‘Unforgiving Consequences’

Governments from the U.S. to Australia are seeking the support of investors and central banks as they seek to spend their way out of the coronavirus crisis. The Federal Reserve has expanded its balance sheet to a record, while the European Central Bank’s program now includes 1.1 trillion euros ($1.2 trillion) of planned purchases this year.

Foreign-ownership of New Zealand sovereign debt has fallen to 50% from 70% just five years ago as policy makers in Wellington snap up bonds as part of a quantitative-easing program. Japan is boosting its debt sales by 18.2 trillion yen ($170 billion) to fund a spending package equivalent to a fifth of its annual economic output.

Under normal circumstances, issuance on this scale would create the conditions for a sharp debt sell-off, and send yields skyrocketing. Indeed, there were signs of this coming to pass in March. But that was before central banks stepped in to pledge debt purchases.

“Can governments continue to borrow at such record levels? No,” said George Boubouras, head of research at hedge fund K2 Asset Management in Melbourne. “Central-bank support is key in the massive bond buying we’ve seen for now. But if they blink then at some point, in the medium term, it will all likely unravel -- with unforgiving consequences for some countries.”

Of course, with no sign of an economic recovery yet emerging, demand for debt will likely remain strong in the near-term. But governments are clearly aware that they’re asking investors to show up week after week.

Several governments, including Germany and the U.K., have opted to syndicate some of their debt rather than auction it to maximize the variety of investors they can access, and to boost the size of their offerings. Nations are also exploring issuing debt with unusual maturities to generate attention and demand, with the U.S. planning to revive 20-year bonds for the first time in more than three decades.

That’s helped markets keep a firm footing so far amid the debt spree. Benchmark 10-year yields in the U.S. have slipped around six basis points this quarter to 0.61%, while German equivalents also saw a similar decline to minus 0.54%.

Inflationary World

But the relatively benign environment may not last. For James Athey, a money manager at Aberdeen Standard Investments, the fiscal splurge combined with de-globalization caused by the pandemic could create an “inflationary world” over the next 18 months. “That’s when you don’t want to be owning bonds,” he said.

Price pressures have so far remained muted, with investors divided over whether inflation could rapidly rebound, or disappear for the long haul.

One option to hedge the risk of inflation returning is a so-called steepener trade, a position that pays off when longer-maturity debt sells off more than shorter-dated bonds. Typically that happens when inflation shows signs of accelerating -- or when there are simply too many bonds in the market for investors to absorb without central bank help.

“Once there is an end to the crisis in sight, they will be less and less willing to provide support and it will fall more on the street to absorb paper,” said Charles Diebel, a money manager at Mediolanum SpA, who’s adding steepeners in anticipation.

Still, that eventuality looks a way off, he said. “For now, the central banks will take all the supply and more.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.